On December 15 last year, fighting that broke out between supporters of South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir and Riek Machar–who had been vice president until Kiir fired the entire Cabinet–escalated into a civil war that has increased pressure on an already fragile independent press.

More than 1.9 million citizens have been displaced, and more than 50,000 have been killed since fighting broke out, according to figures from conflict prevention organization International Crisis Group and the U.N. Against this backdrop, South Sudan’s media have come under orders to show loyalty in their reporting.

In late September I traveled to South Sudan to meet journalists, lawyers, government, and U.N. officials to develop a better understanding of the problems faced by the media there. While journalists have never enjoyed a free press in South Sudan since it gained independence in 2011, contacts I met said conditions had deteriorated further during the civil war. The country’s transitional constitution safeguards press freedom, but it is not adhered to, leaving journalists to censor themselves to avoid harassment and threats.

Even before the civil war authorities were not supportive of an independent press. After a protracted war to gain sovereignty from Sudan, authorities in the newly created country continued to harbor a war mentality that tolerated little media criticism. Now that conflict has resurfaced, pitting South Sudan’s two largest ethnicities (Dinka and Nuer) against one another, authorities have asserted a hardened stance against the press and demanded blanket loyalty.

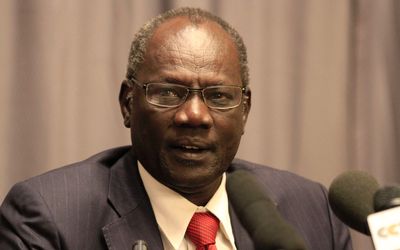

“You are under duty to protect this country. Whenever you are writing or talking on any FM radio, please put your country first. You must be seen to be a nationalist,” Information Minister Micheal Makuei Lueth ordered journalists during a press conference in the capital, Juba, in September.

Once the conflict began, certain topics became no-go areas for local and foreign journalists alike. “After the crisis, if you say anything that is seen as negative towards the government, you are labelled a rebel supporter,” Bullen Kenyi, former chief editor of The Patriot, a privately owned paper that folded due to financial problems in August, told CPJ. Former soldiers turned security agents, accustomed to power over the population during the war of independence, have continued a crackdown on South Sudan’s press with little oversight from superiors.

Since fighting broke out not a single month has passed without incidents of security agents harassing the press, often with little or no pretext, according to CPJ research. Government security forces have raided all major media outlets in Juba this year, according to news reports. Edward Terso, secretary general of the Union of Journalists of South Sudan, estimates at least 32 cases of harassment, intimidation, and arbitrary detentions have been recorded by the union since the conflict began.

But Paul Jacob Kumbo, director of public information at the Ministry of Information, disputed these claims. He told me the government was “committed to protect journalists” but journalists must act professionally and “be aware of guidelines” to ensure their security. He did not state what these guidelines were however.

Security agents have raided and confiscated print runs from the privately owned daily Juba Monitor five times since the conflict began, subjecting them to fiscal losses estimated at about $9,500 each time, its chief editor Alfred Taban said. On two of those occasions, agents targeted the paper for Taban’s columns that proposed a federal government system as a solution to secure peace, he said. Members of the National Security Service had decided the topic was a threat to “national security,” local journalists told me–despite a letter written by Makuei denouncing any censorship of the federalism debate. When The Citizen, another privately owned daily, published the minister’s letter in June, security forces confiscated its print run as well, the paper’s chief editor Nhial Bol said.

Local journalists told me that security agents often conducted operations on an ad-hoc basis, with little supervision or prior knowledge from their superiors. “There are two governments here in South Sudan, the security forces and then the rest,” said Godfrey Bulla, managing director of the former weekly The Patriot. While Information Ministry Undersecretary George Garang Deng told me that South Sudan was “far more free than other countries,” he admitted that security agents often confiscated newspapers and raided broadcasters without consulting them.

With a sprawling untamed security system, local journalists fear covering sensitive topics and self-censor as a means of survival. The most censored topic, despite public interest in the conflict, is any coverage of the rebels.

At press conferences in March and September, Makuei told the media not to cover rebel activity because “you are actually agitating the people against the government.” The minister has yet to provide any legal provisions to justify the apparent ban, and did not state what the penalty would be for those who failed to follow his directive.

One of Makuei’s warnings came after the Juba-based independent Eye Radio interviewed members of the rebel opposition at peace negotiations in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in March. Later that month, security agents interrogated the radio’s chief executive, Stephen Omiri, and temporarily suspended the station’s registration certificate, Omiri said. The editor who approved the story, French national Beatrice Murail, resigned and left the country. “We now have to censor ourselves when it come to reporting the rebels,” said Eye Radio director Koang Pal Chang. “While we’ll have a sound byte from the army spokesman, for example, we will not add a clip from the rebel spokesman.”

In August, security agents raided another major broadcaster, Bakhita Radio, a Juba-based station that makes up one of seven Catholic Radio Network stations in the country. Security officers closed the station for a month, arrested news editor Ocen David, and detained him for four days in a dark room, managing director Albino Tokwaro told me. “They came to the station and lectured the staff for two hours not to report political programmes,” Tokwaro said. “I was forced to write a letter of apology–that we would focus on faith-based programming and not politics.” The station’s crime? Reading an online news report that quoted the rebel spokesman, he said.

Weeks after Bakhita Radio was forced off air, Joseph Garang, deputy governor of Western Bahr El Ghazal State, threatened to close the Catholic Radio Network’s Wau-based station, Voice of Hope, according to news reports. The network reported that Garang told radio staff to distance themselves from political coverage and “concentrate on homilies and Gospel music.”

Media in the rebel-controlled region receive similar, if not worse, treatment as that in government-controlled areas. In January, rebels took over the network’s Malakal, Upper Nile State station, Sout al Mahaba (Voice of God’s Love) and forced the station to air messages from the rebels. “We really did not want to broadcast their information since the station was mainly designed for peace messages, prayers, and to help people find lost relatives,” Catholic Radio Network’s director Eliana Valentina said. The station has been off the air since February due to looting from both sides, she added. In April, rebel forces temporarily captured the oil-rich town Bentiu and commandeered the state radio. Rebels used the station, part of the Unity State Radio network, to broadcast a message to urge men to rape women of specific ethnicities and demand that rival groups be expelled from the town, according to news reports. The strategic town is now under government control. The rebels currently operate two radio stations, local journalists told me, one in Jonglei State and another in Upper Nile State.

The crackdown on the press from both sides has led to a vacuum of critical reporting and a populace starved of information during this crucial, restive period. Bakhita Radio’s “Wake Up Juba,” formerly one of the country’s most lively political talk shows, has become a shell of its former self, managing director Tokwaro said. Many journalists have either quit or gone into hiding, fearing persecution, he said. The once bustling studios of the U.N.-backed Radio Miraya have been reduced to a skeleton staff. Local journalists told me the station is far less critical than in the past, an allegation news editor Patricia Okoed Bukumunhe denies. Other stations such as Liberty FM and City FM no longer cover politics, and Classic FM reports news from pro-government newspapers only, local journalists said.

Out of roughly ten newspapers in regular circulation, only two remain genuinely independent, journalists and members of civil society told me, when asked if they thought news coverage was balanced. In March, National Security Service Director Major General Akol Koor Kuc sent a letter to the Information Ministry accusing the independent Arabic-language daily Al Mijhar Al Siyasi of false publication and conducting “interviews with disgruntled politicians,” Stephen Chang, who used to be a reporter for the paper, said. The ministry also accused the paper of supporting the opposition because several staff were ethnic Nuer, Chang, who has fled into exile, said. The paper’s staff wrote a letter of complaint to the National Security Service and the ministry, citing constitutional protection of freedom of expression, but received no response. The information ministry ordered the closure of the paper the next month, local journalists told CPJ. The paper remains closed.

Since former vice president Machar and the majority of his rebel soldiers are Nuer, authorities categorize all Nuer journalists as opposition supporters. “There’s an assumption of bias,” said Bonifacio Taban, a Nuer journalist who fled in January after a tip-off from government security contacts that he was to be targeted. A reporter for the popular news site Sudan Tribune, Taban faced anonymous phone threats for his coverage of government military operations in Unity State, he told me. In some cases, Nuer journalists are targeted not for their reporting, but for their ethnicity. Nyuon Ruai, a former reporter for the bi-monthly New Nation, said security officers arrested him in November, while he was walking in the street in Juba. The officers detained him for three days at military barracks, accusing him of being a rebel spy, he said. “They took me to an open place, tied me to a tree like an animal and beat me while asking which military battalion I allegedly worked for,” he told me. Ruai, who wasn’t working for the paper at the time of his detention, fled South Sudan soon after. “You can’t work as a journalist in a place where you can be arrested at any time, simply for walking in public,” Ruai said. Only a handful of Nuer journalists remain in South Sudan, the majority having either quit or gone into hiding, according to journalists at the country’s media outlets, and displaced Nuer journalists I spoke to. CPJ estimates at least 21 Nuer journalists have fled into exile or are hiding in internally displaced camps during this conflict period. The figure was determined after interviews with exiled journalists and others I spoke to who are currently hiding in the internally displaced camps in Juba.

Hopes within the media fraternity that three media laws could help protect journalists appear to be dashed. Presidential spokesman Ateny Wek Ateny claimed the bills–the Authority Act, the Broadcasting Corporation Act, and the Right of Access to Information Act–were passed in September. But journalists, civil society groups, lawyers and members of the UN I spoke to all agreed that none have been implemented to date. The Media Authority Act, for instance, should set up a regulator with a board chosen and represented by the media fraternity. But without any signs of implementation, coupled with authorities’ track record of ignoring progressive legislation, the press remains skeptical. “The laws provide freedom of expression but if security organs do not understand this legal right they just become pieces of paper,” Classic FM news editor Dhieu Williams told me. Article 24 of South Sudan’s Transitional 2011 constitution guarantees freedom of expression but authorities rarely abide by it, Issa Muzamil, chair of the South Sudan Human Rights Law Association, told me. “The constitution is a dead document,” he said. “People are only using it when it supports the government.”

Meanwhile, the potential passage of the National Security Service Bill is raising concerns among journalists. If passed, the document would allow security agents to arrest and detain suspects without a warrant, monitor communications including broadcast stations, and seize property. “As [if] war and starvation were not enough for the people of South Sudan, now one of the worst crackdowns on journalists and democratic freedom will be a reality in a new national security bill, making it very difficult to report, live, and act in this place,” a foreign freelancer, who is based in South Sudan, posted on social media. A disagreement by ministers about whether the bill was passed with quorum in parliament last month is likely to delay it being signed into law, according to news reports.

Widespread intimidation of the press with no recourse to legal protection not only affects journalists but the entire country. A lack of independent media to cover South Sudan’s tense situation is making it hard for citizens to gain access to balanced information, and allows government actions to go unchecked. “This conflict will not end without an independent media since people are induced to follow rumors or impartial sources,” former chief editor of The Patriot, Kenyi, told me. “If repeatedly fed the wrong information, citizens will continue to support a conflict few genuinely understand.” Many of the journalists I spoke to said that the peace negotiators were not being directly affected by the conflict because their families were living in safety abroad. When Radio Tamazuj asked Makuei to confirm the station’s claims that delegates in the peace process were paid a $1,000 allowance per day on top of their salaries and benefits, Makuei refused to give details. “Citizens don’t need to know,” he told the station.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The thirteenth paragraph has been corrected to reflect that Beatrice Murail of Eye Radio left the country but was not deported as previously stated. The report has been corrected to reflect that the Arabic-language paper Al Mijhar Al Siyasi is a daily. Some other details of the report have been changed or deleted for the safety of the journalists cited in the original.