As journalists continue to be targeted, the government of Asif Ali Zardari has shown itself unable and unwilling to stand up for a free press. Whatever solutions exist will have to be found by people in the profession. By Bob Dietz

Under Siege, Pakistani Media

Look Inward for Solutions

By Bob Dietz

Speak to journalists in newsrooms or in the field in Pakistan and you will hear stories and opinions about killed and missing colleagues. Within their circle, reporters and editors readily share theories on the identities of perpetrators and their motives. Some whisper of threats they have received. By email, a few send “If I am killed” messages to friends, telling of threats and fears, their suspicions of possible killers and accusations of intent, founded and unfounded. Some ask for assistance in hiding from pursuers or moving between cities. Others want help to flee the country. Some have already gone.

Their concern is quite real because colleagues are being abducted, beaten, and killed in Pakistan at a rate higher than anywhere else in the world. While a few journalists simply disappeared, the bodies of most victims turned up soon after their death, their corpses apparently meant to serve as a warning to others.

The record is brutal. Pakistani journalists are vulnerable prey for many of the violent actors in their country–militant and extremist groups, criminals and thugs, street-level political groups in densely populated cities like Karachi, and, despite official denials, the military and security establishment. In 2010, Pakistan ranked as the world’s deadliest country for journalists, and with 41 dead since CPJ started keeping detailed records in 1992, it ranks historically as the sixth worst in the world. The pace was similar in 2011, coupled with an apparent increase in death threats to journalists. Though some cases have drawn international attention and been subjected to high-profile investigations, all but one remain unsolved. Except when some of the men complicit in the murder of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl were brought to justice after his 2002 beheading, there has been perfect impunity for those who kill journalists in Pakistan.

Decades of ineffectual governments demonstrate that journalists cannot expect justice should they become targets of any of the country’s many violent actors. But within Pakistan’s vibrant and financially successful media culture, some professional groups are taking proactive steps that, coupled with the manpower and financial support of media houses, could help address these problems without the government. In the meantime, some journalists will continue to censor themselves, give up the profession, or flee the country.

The most prominent murder in 2011 was that of Saleem Shahzad, 40, who disappeared on May 29, soon after a two-part article about Al-Qaeda infiltration in Pakistan’s navy appeared in Asia Times Online. His body was found on May 31 floating in an irrigation canal near the town of Mandi Bahauddin, about 75 miles (120 kilometers) south of the capital, Islamabad. His white Toyota Corolla was parked nearby.

Shahzad’s book, Inside the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, had been released about 10 days before he was beaten to death. In it, he used insider information to link a small cadre of military officers to fundamentalist groups. Shahzad’s reporting angered some factions within the military and intelligence community, but he had been diligently promoting his book on Pakistan’s contentious political television programs despite the rising threat level. He was reported missing when he failed to show up at one of those televised panels, where he had intended to discuss the Asia Times Online piece, which claimed that Al-Qaeda was behind the 17-hour siege at a naval air base in Karachi on May 22. According to Shahzad, the attack came after the military refused to release a group of detained naval officials suspected of being linked to militant groups.

Earlier in April, three navy buses carrying recruits were blown up via remote-control devices in Karachi, the large port city where the navy is headquartered. In retrospect, those attacks were most likely the precursor to the all-out assault on the base, and Shahzad had said so. Further, his disclosures came just a few weeks after the U.S. killing of Osama bin Laden deep within Pakistani territory.

For months, Shahzad had been telling friends that he was trading text messages with intelligence agents and had been summoned to meetings with them. He had been directed to stop reporting on security matters that caused trouble for the military. Shahzad told a friend, Ali Dayan Hasan, a researcher for Human Rights Watch in Pakistan, that he had been threatened by a top official during an October 2010 meeting at the headquarters of the government’s powerful Inter Services Intelligence Directorate, or ISI.

Hasan said Shahzad had sent him a note describing the meeting “in case something happens to me or my family in the future.” Hameed Haroon, president of the All Pakistan Newspapers Society and one of Shahzad’s former employers, told Human Rights Watch that he received a similar message about the same time.

Given those threats, it is understandable that friends who raced to see Shahzad’s body before he was buried told CPJ that his face and neck showed signs of torture. But, according to the post-mortem report, it seems likely that Shahzad was not tortured until he died, at least not in a manner that would be used if his assailants were seeking to extract information from him. Instead, he was most likely beaten to death quickly and brutally in a manner that would intimidate other journalists.

His killing had the apparently desired chilling effect: Many journalists in Pakistan openly admit they were intimidated. Reporters covering security matters said they had received the sorts of threats and abuse that Shahzad had been receiving. Others started talking of threats from other sources, including ground-level political groups in restive areas such as Karachi, Baluchistan, and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. For some, intimidation is part of the cost of doing business, and they have learned when to dial back a story to avoid more serious consequences. Their editors understand. The result is an institutionalized self-censorship that undercuts the power of Pakistan’s historically assertive news media.

“You don’t know what it is like to spend all your time worrying about an attack and where it might come from,” said one journalist who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal. “The fear affects more than just your reporting. It makes you worry about the safety of your family. It is a powerful thing that takes over your life.”

After Shahzad disappeared and in the weeks after his death, the journalism and human rights communities accused the ISI of complicity. The agency denied involvement, but public anger forced President Asif Ali Zardari to form a five-member commission headed by Supreme Court Justice Mian Saqib Nisar to hear testimony. (Similar panels have been convened in other killings and attacks on journalists. None have been conclusive.)

Before Shahzad’s death, Pakistan’s patriotic and nominally pro-military media had stepped up criticism of the military and intelligence establishments with portrayals of official ineptitude in the Karachi naval attack and the U.S. raid on bin Laden. The criticism escalated after Shahzad’s murder, but eventually the story moved on. The United States stirred up nationalist resentments with increased rhetoric about ISI support for certain factions of the Taliban, and the Pakistani media began to speculate about a U.S. invasion of Pakistan. By fall, the press had returned to its earlier, pro-military stance. The special inquiry into Shahzad’s death had issued no findings by late year.

There was precedent for Shahzad’s murder. In December 2005, freelancer Hayatullah Khan, who for years had been under threat from government officials and militant groups in North Waziristan, took photographs of the remnants of an American-made Hellfire missile that had hit a house inside Pakistan, apparently targeting senior Al-Qaeda figure Hamza Rabia. Khan’s pictures for the European Pressphoto Agency directly contradicted the Pakistani government’s claim that Rabia had died in a blast caused by explosives in the house. At the time, the military-backed government of President Pervez Musharraf was denying that the United States was violating Pakistani territory with military operations inside its borders. Khan supplied some of the first proof of what later came to be common knowledge.

Like Shahzad six years later, Khan was abducted and died a violent death after discrediting the military. He was grabbed by gunmen on December 5, 2005, the day after his pictures were published worldwide. On June 16, 2006, he was found in his hometown of Miran Shah. His body had multiple gunshot wounds and had been ritually shaved in the Islamic manner used to prepare a corpse for burial, family members told CPJ. On his left hand dangled the distinctive sort of handcuff used by the military.

Musharraf ordered an investigation, in this case by High Court Justice Mohammed Reza Khan. The judge delivered his report in September 2006, but the results have never been made public. In July 2007, then-Interior Minister Aftab Ahmed Khan Sherpao and then-Secretary of the Interior Syed Kamal Shah pledged in a meeting with CPJ in Islamabad to release the report. The call for publication continued to be made over the years. On May 3, 2011, World Press Freedom Day, in a meeting with President Zardari and Interior Minister Rehman Malik, CPJ made the request again. The report has yet to be released.

Khan’s death still resonates with journalists in Pakistan. As CPJ reported in the 2009 series, “The Frontier War,” reporters have faced pressure from all sides to censor their work amid the deepening conflict along the border with Afghanistan. While those journalists remaining in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas have become a major source for news on fatalities from U.S. drone strikes, reporting on the struggles between militant factions, villages, and religious groups is highly restricted. Many local journalists have left the profession or report on only the most benign topics.

The intimidating effect of threats and attacks, not to mention deaths, drives some journalists to leave the country altogether. Since December 2010, CPJ’s Journalist Assistance program has processed requests for help from 16 Pakistani journalists who have received threats from police, military, paramilitary, and political organizations. Fearing for their safety, most have asked that their individual cases go unpublicized. After Shahzad’s death, requests for assistance started to climb, a trend that continued through late year.

Waqar Kiani, 32, who in the past had been a local correspondent for the British newspaper The Guardian, survived two assaults before resolving to leave Pakistan. In 2008, he was abducted in Islamabad by suspected intelligence agents, blindfolded, beaten, and burned with cigarettes. His ordeal ended 15 hours later when he was dumped 120 miles (180 kilometers) outside the city. Kiani told CPJ his abductors had threatened to rape his wife and post the video on YouTube if he told anyone what had happened. Traumatized, Kiani continued to freelance, telling only his closest friends and colleagues of the ordeal. He did not go public with the story until, caught up in the public anger surrounding Shahzad’s death, he gave an interview to The Guardian about his own abduction and torture, then discussed it on political talk shows.

On the night of June 18, 2011, a few weeks after Shahzad’s killing, a police van pulled Kiani over and ordered him out of his car. They wanted to search it, the officers said. As he stepped out, he told CPJ, four officers started to beat him with sticks and a rubber whip. They taunted him: “You want to be a hero? We’ll make you a hero. We’re going to make an example of you,” the journalist said. Kiani was beaten on his face and back so badly that Declan Walsh, The Guardian‘s Pakistan correspondent at the time, raced to the scene to transport him to a nearby hospital.

Soon after Kiani’s second beating, Interior Minister Malik ordered separate judicial and police inquiries. But after Islamabad Senior Superintendent of Police Tahir Alam said preliminary investigations showed that police were not involved in the attack, the investigations stopped. Kiani lowered his profile as a journalist and with the help of The Guardian, he left the country for a few months, waiting for the threat to fade.

After Kiani returned to Pakistan, he told CPJ, he was convinced that he and his family remained under threat. He left Pakistan a few weeks after returning home. Temporarily separated from his family, he was seeking asylum in a European country in late year.

Another Pakistani journalist, Malik Siraj Akbar, is now based in Washington. He fled Pakistan because of military action in his native Baluchistan province, where secessionist groups battle each other and the Pakistani military, and where his exposure of military abuses would, he believed, make him a target. Soon after he was given political asylum in the United States, he told CPJ, “While I know the life of an asylum-seeker is often marked with extraordinary hardships, demise of one’s professional career, and complete disconnection with friends and families, I believe no story is worth dying for.”

The Pakistani security services are far from the only suspects in cases of attacks on journalists. Sometimes it is impossible to narrow down who may be responsible because of the sheer number of potential culprits. On May 10, about 700 miles (1,100 kilometers) due north of Karachi, in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas along the border with Afghanistan, Nasrullah Khan Afridi was killed when his car exploded in a crowded market in Peshawar. According to his colleagues at the Tribal Union of Journalists (Afridi was the union’s president), he had been receiving threats for years from just about every combatant group along the border with Afghanistan–the government, Taliban groups, gun runners, and the military. No one knows whom to blame for the targeted killing of this prominent regional reporter who worked for Pakistan Television and the Urdu-language Mashreq.

Luckier than Afridi was television reporter Naveed Kamal. Two assailants shot at him in April on his way home from the small, low-budget cable TV station Metro One where he was a reporter. The motorcycle-riding gunmen fired repeatedly, hitting him with one round to the right cheek that shattered his jaw and exited his left cheek. Lying on a bed recovering at his parents’ house in Karachi, Kamal told CPJ that police had conducted only a desultory investigative interview with him. He said he fully expected there would be no arrest made in his case. The last story Kamal had covered described the flags and banners that political groups were flying over specific neighborhoods–an indicator of the turf wars in Karachi among partisan and criminal organizations. Kamal said he did not know which group went after him or why. Although he later returned to work, he faced ongoing threats that forced him to switch beats.

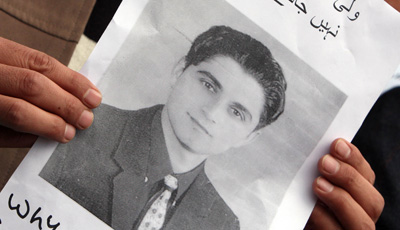

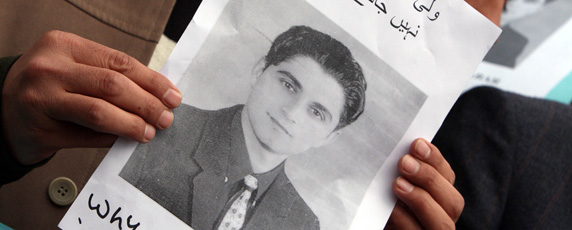

The most fully, but still unsuccessfully, investigated journalist murder case of 2011 was the January 13 killing of Wali Khan Babar, a popular general news reporter in Geo TV’s Karachi bureau. He was gunned down after filing a report on gang violence in the city, the country’s most violent. In April, a few widely publicized arrests of low-level suspects were made; all were members of the Mutahida Qaumi Movement, or MQM, the country’s third largest political party. But after four witnesses to the killing were shot and killed, as well as the brother of the police officer leading the investigation, the case went fallow. A spokesman for the prime minister’s office told reporters that it considered Babar’s murder a provincial matter, with the federal government having no role in continuing or ending the investigations. Because the suspected mastermind reportedly lives abroad, local authorities say the case is the federal government’s responsibility. A perfect jurisdictional Catch-22 has stalled the investigation.

Sitting at his desk in Geo’s newsroom, News Director Azhar Abbas picked his words carefully. “No less a person than the home minister [Malik] has named the MQM in the killing of Wali Khan Babar,” he said. “The arrests in the case so far are linked to the MQM, and the MQM has not distanced itself from the killing. The onus is now on the MQM to say if it was involved or not.” The MQM has denied any involvement in Babar’s death.

When Zardari met with a CPJ delegation on World Press Freedom Day, he pledged that he would address Pakistan’s appalling record for unprosecuted murders of journalists. So far his government has taken no action, in some cases because it apparently chooses not to, in others because it has no control over the actors. But the milieu in which Zardari rules and journalists operate is reeling out of control. A May report from the Center for Strategic International Studies identified 2,113 terrorist attacks, 369 clashes between the security services and militants, 260 operational attacks by the security forces, 135 U.S. drone attacks, 69 border clashes, 233 bouts of ethno-political violence, and 214 inter-tribal clashes in 2010. In all, more than 10,000 people died and about the same number were injured. The data being compiled by other organizations for 2011 looked to be similar.

With violence at a high level, special investigations proving fruitless, and an ineffective, impotent government unable or unwilling to protect them, Pakistani journalists have come to realize they must act on their own. Already, there are noteworthy instances of unity: When Umar Cheema, a prominent political reporter for the English-language daily The News (and a recipient of CPJ’s International Press Freedom Award), was abducted on September 4, 2010, held overnight, stripped, beaten, humiliated, and abused before being bound and dumped on a roadside, the English-language daily Dawn, a direct competitor of The News, voiced its solidarity and anger. In an editorial, Dawn‘s staff wrote: “No half-hearted police measures or words of consolation from the highest offices in the land will suffice in the aftermath of the brutal treatment meted out to journalist Umar Cheema of The News. This paper’s stand is clear: The government and its intelligence agencies will be considered guilty until they can prove their innocence.”

Founded more than 50 years ago, the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists and its local chapters have long been a source of protest and pressure on the government when it comes to journalists’ safety. The groups regularly turn out to protest attacks on colleagues in other cities, and there is a strong identity of journalism as a profession and a culture. The country’s abysmal record of impunity has strengthened the groups’ resolve, if not its ability to reconfigure Pakistan’s culture of violence.

Journalists and media companies have put some basic steps in place. To remind reporters and photographers to take precautions while covering everyday violence, Dawn displayed posters and distributed handbooks for field crews with safety tips drawn from detailed guides by CPJ, the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), and other international journalist organizations. IFJ has prepared posters in Urdu. Dawn‘s sister organization, Geo TV, has done something similar and is backing up the guidelines by sending select staff members abroad to get practical, if expensive, training that they pass on to their colleagues. The Khyber Union of Journalists issued its own coverage guidelines after the double bombing of a market in Peshawar on June 11 that killed two reporters.

Concerned by the violence, after meeting with President Zardari and Interior Minister Malik on May 3 and 4, CPJ hosted a discussion on May 5 in Karachi. Haroon, who is chief executive of Dawn Media Group along with heading the All Pakistan Newspapers Society, led a conversation about the creation of a press organization to monitor and compile data on anti-press attacks. Haroon wants to create a hub of experts and gather knowledge about the assaults, kidnappings, and murders of journalists over the years.

Others in Karachi have a similar idea. The Citizen Police Liaison Committee is a private organization, run by the local business community. It supports a 24-hour hotline to police and the Interior Ministry. The idea arose in the 1990s when the abductions of wealthy businessmen in Karachi were a serious problem. The committee met with some success in solving the problem, though it was far from a total success. Zaffar Abbas, the editor of Dawn, suggested that a similar model would work for members of the journalist community when threatened or in immediate danger. Amin Yousuf, the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists secretary-general at the Karachi Press Club, said the union would be interested in working with such a group. The task is to bring the two ideas together.

Pakistan’s media are vibrant, with the larger groups commercially successful and the smaller ones proving viable over the long term. Large and small, they are owned by strong-willed, successful businesspeople with deep political connections, part of the country’s ruling class. For now, whatever solutions exist will have to be found by people in the profession. Among their many challenges will be confronting a government unable and unwilling to stand up for a free press.

Bob Dietz, coordinator of CPJ’s Asia program, has reported across the continent for news outlets including CNN and Asiaweek. He led a CPJ mission to Pakistan in April and May 2011.