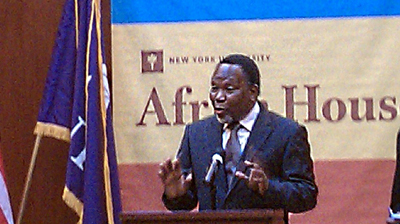

On Monday, in a public lecture at New York University, South African Deputy President Kgalema Motlanthe described as irreversible the democratic gains made since the end of apartheid, including the advancement of press freedom. “We have a constitution which guarantees basic human rights such as freedom of association, freedom of the press, and the independent judiciary,” he declared. Many in South Africa, however, are not so sure that press freedom’s future is secure.

During a Q&A session following the speech, I put to the deputy president the perception that South Africa’s status as a press freedom haven was in jeopardy because of the African National Congress’ increasing antagonism toward the private press. I referenced the controversial Protection of Information Bill, dubbed the “Secrecy Bill” by critics because it would give officials unchecked authority to classify any information in the name of vaguely defined “national interest.” I also referenced an ANC proposal to set up a media appeals tribunal run by parliament, a chamber dominated by ANC politicians, some of whom have been rightly or wrongly implicated in scandals of wasteful spending and corruption. Noting fears that South Africa might return to apartheid-era secrecy and press censorship, I offered the deputy president a chance to clarify the government’s commitment to press freedom.

My question triggered an instant reaction on Twitter from Nadia Neophytou, a New York-based South African journalist who was in the audience. “Issue of press freedom in SA has come up,” her tweet said in part. In response, Deputy President Motlanthe restated that press freedom is guaranteed by the South African Constitution. Then, in great detail, Motlanthe told a personal anecdote that appeared to cast the South African press in a single, simple caricature. “#Motlanthe is telling the story of the false headlines claiming he fathered a child” noted Neophytou on Twitter. “One morning I woke up to see a headline that read, ‘President impregnates 24-year-old’,” the deputy president said, adding “Not a word to check with me; they did not ask me if I know this girl.”

“That story about [Motlanthe] was ridiculous,” Lihle Mtshali, a New York-based columnist for Sunday Times, told me later. But Mtshali, who was using a hashtag for the occasion (#MotlantheinNY) on her Twitter account, took exception to Motlanthe’s portrayal of the South African press. “To make it look as if we all treat our subjects as tabloids do is completely wrong.”

Motlanthe further complained that the retraction of the story was not as prominent as the original headline, and said this was the basis for the ANC’s proposal to “investigate the desirability” of a statutory media appeals tribunal. He restated an earlier position that such a tribunal would not come into existence as long as self-regulatory mechanisms for the press were reinforced. “If indeed the print media is able to expand the capacity of the press ombudsman and give equal prominence to the retractions, I’m sure the ANC will say in its next conference that there is no need for this resolution.”

Motlanthe accused the press and activists of “conflating” the media appeals tribunal proposal with the Protection of Information Bill and then wrongly claiming they would “kill press freedom.”

Yet there seems to be plenty of potential danger from the Protection of Information Bill. Investigative stories based on leaked documents would simply disappear; that includes stories such as the alleged wasteful spending scandal surrounding a trip to New York by a delegation of 49 South African officials for a U.N. Gender summit. The Sunday Times journalists who broke the story over the weekend could be prosecuted and sentenced for up to 25 years in prison.

Motlanthe appeared to take offense at the public outcry triggered by the ANC’s proposals, saying critics “were not debating the issue and instead waged a campaign.” In fact, the administration has refused to amend the worst provisions of the bill, rebuffing suggestions to impose independent oversight of classification and to allow public interest as a defense for journalists. Further, activists say the ANC has dragged its feet in responding to proposals for media self-regulation reform.

Finally, Motlanthe attacked journalism training in South Africa. He charged that “journalists are trained to believe the government by nature is inherently corrupt.” The assertion reflects the ANC’s recent use of hostile rhetoric toward the press. “It’s quite disconcerting to hear someone so high in government say such things about media,” said Mtshali of the Sunday Times. “I don’t know any newsrooms where reporters are told not to trust government. We are taught from the the beginning to get facts and only facts.”

Describing the natural skepticism of journalists, Mtshali said: “We are not always going to agree with what government says. We are going to call them out on some things.”