An alleged sex scandal involving one of the wives of Africa’s last absolute monarch, King Mswati III of Swaziland, has made worldwide headlines. Yet, in the southern African mountain kingdom, media coverage has been subdued, shying away from questioning the silence of the monarchy over the reports.

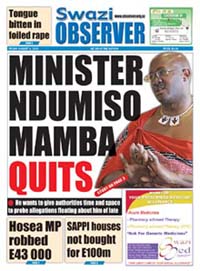

So, while City Press, a newspaper in neighboring South Africa, went as far as publishing an exclusive photo showing the alleged moment when married Swazi Justice and Constitutional Affairs Minister Ndumiso Mamba was caught in a hotel room with the Inkhosikati LaDube, King Mswati’s 12th wife, both the government daily and leading independent newspaper Times of Swaziland barely reported that the minister was forced to resign following unspecified “allegations” about him.

The Times, however, reported that Swazi plainclothes police arrested a man on Tuesday in the commercial capital, Manzini, for photocopying the City Press article. The paper quoted Swazi Police Deputy Public Relations Officer Superintendent Wendy Hleta as confirming that the Criminial Investigation Department had charged the man with “contravening the Copyright Act.”

No wonder. Media in Swaziland, a small country landlocked between South Africa and Mozambique, is strictly controlled by the king. All radio stations are under the state agency known as the Swaziland Broadcasting and Information Service (SBIS). The head of the government, Swaziland Prime Minister Barnabas Dlamini, is editor-in-chief of SBIS and state television station Swazi TV. The only other TV station in Swaziland, Channel Swazi, is privately owned but follows the monarch’s line in news broadcasts. One of Swaziland’s two newspaper groups, the Swazi Observer Group, is part of a company that is in effect owned by King Mswati. That leaves the Times of Swaziland as the only independent newspaper in the kingdom.

Media is generally frightened of the power the king wields. The Times has fallen afoul of him in the past. In 2007, King Mswati ordered the Times Sunday to publish an apology for an article it sourced from Norway that said the king was partly responsible for Swaziland’s economic ills. He also demanded that the features editor of the Times Sunday be dismissed for allowing the report to be published and warned the newspaper never again refer to him as a “dictator” (even though the report did not use this word). The King said if his demands were not met he would close down the Times Sunday and the other newspapers published by its owner. The publisher went along with the demands.

More recently, in 2009, the Times was forced to make an abject public apology to King Mswati after it reported that he had bought 20 luxury and armored Mercedes Benz S600 Pullman Guard cars that cost US$250,000 each. The story was true and had been published extensively by news media internationally.

As a result, censorship and self-censorship is rife in the Swaziland media. Research published by the Media Institute of Southern Africa in 2008 revealed that fear of the monarchy and the power it has over the kingdom and media houses within it was by far the main cause of censorship in Swaziland. This is both the censorship imposed by King Mswati and self-censorship. There are also high levels of self-censorship around the king and the queen mother, since editors, aware of threats made in the past by the king, do not want to get themselves into trouble. There is a rule, generally accepted among journalists in all media houses, that you don’t criticise him.

There are serious concerns about human rights generally and media freedom in particular in Swaziland. The U.S. State Department in its review of human rights in Swaziland for 2009 reported: “The constitution provides for freedom of speech and of the press, but the king may waive these rights at his discretion, and the government restricted these rights during the year. Although no law bans criticism of the monarchy, the prime minister and other officials warned journalists that publishing such criticism could be construed as an act of sedition or treason, and media organizations were threatened with closure for criticizing the monarchy.”

As if to illustrate this point, last month, King Mswati’s elder brother, Prince Mahlaba, declared in a public conference that “journalists who continue to write bad things about the country will die.” However, as Times of Swaziland columnist Vusi Sibisi pointed out in an August 4 column: “Contrary to popular opinion within government, the media is not a lapdog to sing praises of the political establishment. The media have a far important and crucial role of ensuring transparency and public accountability instead of singing praises whatever the size of the carrot government dangles to journalists or the threat of the stick it wields to drive the fear of God into scribes.”

Richard Rooney is a former associate professor in journalism and mass communication at the University of Swaziland. He blogs at Swazi Media Commentary.