A Chinese dissident who writes about rights abuses is ending an involuntary exile in Japan on Friday. Or so he hopes.

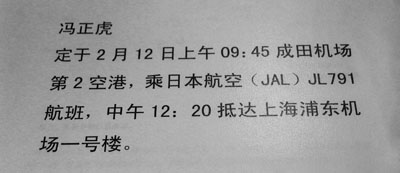

Feng Zhenghu has booked a flight departing Japan’s Narita Airport for Shanghai at 9:45 a.m. on February 12. That was the topic of an impromptu press conference held Monday afternoon in the brightly lit lobby of the Nippon Press Center Building in central Tokyo. A small crowd of Chinese and Japanese journalists clustered round him snapping photos while an anxious security guard paced up and down, interrupting every now and then to ask the group to disperse.

Travel arrangements don’t usually constitute breaking news, but Feng’s recent attempts to fly home have drawn international attention. Chinese airport security have repeatedly refused him entry to the country since his scheduled return in June 2009. His last flight, on November 3, ended with police at Shanghai’s airport bundling him back onto a return flight the next day. Feng has a valid Chinese passport and was given no reason for the action.

Instead of settling back down in Japan, Feng, at left, elected to camp out in the immigration hall. Ninety-two days passed, as did several tense visits from security representatives from both countries, before he finally received assurances from Chinese authorities last week that he would be allowed home.

Over coffee in the plush interior of the Japanese National Press Club upstairs in the Nippon Press Center, Feng, an economist by training, described how he came to earn the ire of Shanghai’s local government. A pro-democracy activist since 1989 and a passionate defender of the rule of law, two years ago he began printing and distributing a bulletin on local rights abuses called Ducha Jianbao (“Supervision Report”). Roughly a thousand copies of the publication—almost all his own reporting—are issued at personal expense a few times a month, calling attention to cases of injustice. His persistent activism hit home: While he was in Tokyo, where he has both family and business interests, someone decided that they’d rather not have him back again.

A calm, well-dressed man in his mid-40s, Feng blends among the middle-aged Japanese men at the Press Club. His suit and tie might almost convince the casual observer that he might take an attempt to exclude him from his homeland lying down. Only a glint in his eye suggests the stubbornness, the sense of mischief, and the flare for self-promotion that characterized his airport stakeout, which he performed in a scruffy white T-shirt with the details of his injustice scrawled across the front in black marker for the benefit of fellow travelers. Narita is a well-equipped airport with shower, food, and rest facilities aplenty, but taking advantage of those would have meant re-entering Japan. He lived on biscuits.

Feng’s confident that by Friday evening he will be home. But the reception that awaits him is uncertain at best. This doesn’t deter him: He’s been ruthless in documenting his own battle for justice, on Twitter and in numerous media interviews, and has no intention of stopping doing the same on behalf of others.

We discuss the possibility of arrest—18 out of 24 journalists currently imprisoned in China were jailed for working online. Feng himself was imprisoned from 2001-2003 for illegally publishing a business directory, and detained without charge for several days in 2008 and 2009. He described the hassle his supporters caused by amassing outside the detention center in protest. “I’ve been arrested,” he scoffed.

So Feng report will continue to publish his report. “Did you never think about giving it all up?” I asked. Feng shook his head and grinned, saying, “I’m having much too much fun.”

(Reporting from Tokyo)