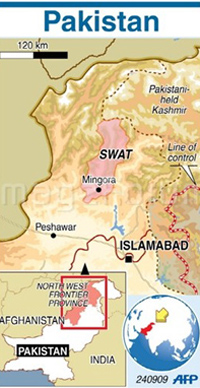

The September 30 Daily Times in Pakistan headlined a story “Peace being gradually restored in Swat,” although daily skirmishes continue between the military and militants. A few days earlier, a massive car bomb in the heart of Peshawar killed at least 10 people and left some 70 wounded, while an explosion destroyed a police station in Bannu. Qari Hussain Mehsud, a Taliban commander in North Waziristan told The Associated Press that his organization had become only stronger after leader Baitullah Mehsud had been killed in a missile strike, most likely fired from a U.S. drone. Clearly, the government offensive that started in April to reclaim the Swat Valley and surrounding areas from militant groups has not marked the end of conflict. Journalists, many of them local reporters who are in the middle of this fighting, will continue to face extraordinary risks and difficulties.

The September 30 Daily Times in Pakistan headlined a story “Peace being gradually restored in Swat,” although daily skirmishes continue between the military and militants. A few days earlier, a massive car bomb in the heart of Peshawar killed at least 10 people and left some 70 wounded, while an explosion destroyed a police station in Bannu. Qari Hussain Mehsud, a Taliban commander in North Waziristan told The Associated Press that his organization had become only stronger after leader Baitullah Mehsud had been killed in a missile strike, most likely fired from a U.S. drone. Clearly, the government offensive that started in April to reclaim the Swat Valley and surrounding areas from militant groups has not marked the end of conflict. Journalists, many of them local reporters who are in the middle of this fighting, will continue to face extraordinary risks and difficulties.

I went to Peshawar and Islamabad recently to talk with Pakistani journalists who covered the military’s first all-out assault against militant groups that had spread beyond their traditional stronghold of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas along the border with Afghanistan into the neighboring Swat Valley and Mingora district. In a series that we’ll post over the next five days, I’ll describe the pressures Pakistani journalists face in covering the fighting, the restrictions on their coverage, and the thoughts of a reporter who embedded with the military. Our series will revisit the 2006 killing of frontier journalist Hayatullah Khan; the government has not only failed to solve this case, it has kept secret its own investigations. And I’ll offer recommendations on how to take some of the pressure off Pakistani journalists who are covering a war of global importance that is being fought in their own hometowns.

Some of these journalists, in fact, lost their homes. Behroz Khan was one.

On the night and early morning of July 8 and 9, a group of armed men came to Khan’s home in Balo Khan village in the dusty district of Buner in Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province. A month before, armed men had ransacked and looted the house; a failed arson attempt had followed that. The houses in Buner are not easily destroyed: They are stout, with thick earthen brick walls, generations old. But on this occasion in July, the men left nothing to chance. After ordering everyone out, they dynamited the home, destroying it. At virtually the same time, a similar attack was carried out at the home of another prominent Buner journalist, Rahman Bunairee.

Khan reported for Pakistan’s English-language daily The News for years from the border areas with Afghanistan. His family is wealthy, with land holdings and businesses in their district. They have been there for generations, and could be considered among the landed gentry of the ethnically Pashtun area. Khan has been a regular contact for CPJ for years, and I met with him and some 20 other journalists from the area in July in Peshawar, capital of the North West Frontier Province, or NWFP, and the jumping off point for journalists covering the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

In a national broadcast on May 7, Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani had gone on the air to announce that Pakistan was at war. Operations had started on April 27 with attacks on insurgents in several small towns; they were in full swing through May and June.

The combat, which is ongoing, is unique in Pakistan. The Pentagon called it the largest military operation that the Pakistani government had ever carried out. It was an all-out assault by the Pakistani military on what is generally reported to be the Taliban, but could be more accurately described as sometimes united clusters of militants with local political and economic ties, some operating from a sense of religious obligation. Some have cross-border links with Pashto and Taliban organizations in Afghanistan, but most have a narrower, sometimes village-level power base. Some have criminal ties, including involvement in the opium trade.

In the year or two before the military’s attacks, the militants had spread beyond the neighboring Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), where the government has never held full authority over the local population, largely ethnic Pashtuns. They administered courts, settled disputes, enforced traditional dress codes and either overran police stations, or used the police to administer the harsh justice they were meting out. To many residents they offered an antidote to the inefficient and corrupt policies that had been passed down from Islamabad. Many Pakistanis across the country saw them as fellow Muslims and countrymen unfairly demonized and attacked by the United States in a spillover from the war in Afghanistan.

There were two distinct groups of journalists who covered the fighting in and around Swat. Khan and Bunairee were typical of the local journalists across the NWFP. About 260 local reporters wound up joining the general population in fleeing the all-out attacks by the Pakistani military, according to the Khyber Union of Journalists. Some stayed behind to take their chances, but their coverage was severely limited by the danger. Much of the coverage was ultimately left to Pakistani reporters from outside the region who had embedded with the military. They confronted the limitations that embedding implies: skewed viewpoints, self-imposed censorship, and outright military control of information.

The attack on Behroz Khan’s house, while extreme, was not unique. Many of the journalists I met said they were under pressure from all sides; even those who were long-term residents felt there was little to no room to operate neutrally in the battlefield. Several said that self-censorship, born out of fear of retribution, was a reality to which they had long ago resigned themselves.

Why were Khan’s enemies so adamantly determined to destroy his house? “I never received any threat,” he said. “But when these men used to visit our village, they would ask for the names of me and my brothers and cousins. But no one has claimed responsibility.”

The same night they dynamited Khan’s house, militants also blew up the house of Rahman Bunairee. There was no doubt, in this instance, as to their reason: They told Bunairee’s family they were retaliating for his reporting.

“They had come to destroy our house, and they told us so. They told my father, ‘We have orders to blow up the house because of your son’s criticism of the Taliban.” he said. Bunairee was a popular reporter for Khyber TV, a national, privately owned broadcaster in Pakistan, and the U.S. government-funded Voice of America’s Deewa service, which targets the Pashto-speaking audience in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border area. Bunairee thinks it is because of his reporting on VOA that he was singled out for retribution.

After the explosion, Bunairee joined his wife and four children in Pakistan’s southern port city of Karachi. Khyber and VOA offered him support as he sorted out what to do next, but he didn’t have the luxury to think for long. Around July 20, in separate incidents, small groups of gunmen climbed the wall at Khyber TV’s Karachi bureau looking for Bunairee. He wasn’t in the office when they came for him, he told me. He was holed up in a guest house in the capital, trying to figure his next move.

He did not know exactly who his assailants in Karachi were—or at least he didn’t feel safe speculating—but he said he knew they were a militant Islamic group angry with his reporting. A few days later, Bunairee fled the country for the United States, reluctantly leaving his family behind as he sought refuge for them all.

The series:

Part 3: Coverage of the fighting was left in large part to Pakistani reporters from outside the region who had embedded with the military.

Part 4: Hayatullah Khan was murdered in 2006 in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. The government investigated—and then kept its reports secret.

Part 5: Government, media can undertake reforms to improve security.