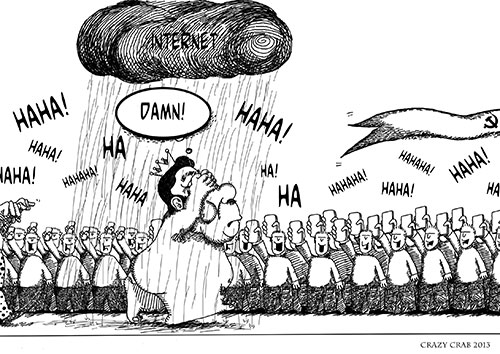

1. Beyond censors’ reach, free expression thrives, to a point

By Sophie Beach

On March 24, 2012, investigative journalist Yang Haipeng posted on his Sina Weibo microblog a story he had heard that alleged a link between Neil Heywood, an English businessman who had been found dead in a Chongqing hotel, and Bo Xilai, the powerful Chongqing Communist Party chief. His post is widely recognized as the first significant public mention of a connection between the two men and it spread like wildfire online before being deleted the next day. A month later, Yang’s Sina Weibo account, which had 247,000 followers, was shut down.

Yang’s experience shows both the power and the limitations of the Internet in advancing free expression in China. Within days of Yang’s post, the world knew of the connections between Heywood, Bo, and Bo’s wife, Gu Kailai; Gu has since been handed down a suspended death sentence for Heywood’s murder and Bo has been expelled from the Communist Party and is facing criminal charges. But Yang, a well-respected and popular journalist and microblogger, is still prevented from communicating freely with his followers on Sina Weibo, China’s most popular microblogging platform.

CHALLENGED IN CHINA

• Table of Contents

Interactive graphic

• Internet Use

Video

• Censored: An Inside View

In print

• Download the pdf

In other languages

• 中文(pdf)

Over the past 10 years, China’s media environment has been transformed by the explosion of the Internet and, since 2010, the phenomenon of weibo, or microblogs, which now have more than 309 million users. Weibo have created a new online ecosystem where news breaks and spreads faster than censors can catch it. This in turn influences public opinion of, and political responses to, certain events. News of the high-speed train crash in Wenzhou in 2011, which killed 40 people, first broke on weibo. In 2011, there were 4.5 million microblog posts on the story, according to a white paper by business intelligence firm CIC and Ogilvy Public Relations—most of them criticizing the government’s poor handling of the disaster. Partly as a result, authorities imposed stricter safety regulations on high-speed train networks. While the Chinese government has justified its control over the media and Internet as a way to prevent social instability, the Wenzhou train crash provides one example of how freer expression in China can help advance the public interest.

However, while discussions on weibo are much more freewheeling and open than elsewhere in the Chinese public sphere, strict limitations on what topics can be broached are still firmly in place. Posts are censored, accounts are closed down, and search results are filtered for sensitive political content. The proliferation of rumors has justified widespread crackdowns on unwelcome content. Weibo users have been questioned and, occasionally, imprisoned for content that they post.

The Chinese government did not respond to CPJ’s written request, sent via the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., to comment for this report.

Beijing clearly sees the economic benefit of fostering communications technology. While blocking popular global social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter, the Chinese government has encouraged domestic equivalents as a way to boost growth and innovation. The results are impressive: Sina Weibo is a feature-rich, user-friendly platform that enjoys immense popularity, as do other social media sites such as Tencent, which provides the second-largest microblogging platform, YouKu, a video-sharing site, and Renren and Kaixin, Facebook-like social networking sites.

Yet these companies are caught between their users, who often demand more freedom, and censorship authorities, who require the companies to self-censor their platforms or risk losing their license to operate. Companies that did not comply with government expectations did not excel in the market: For example, Fanfou, China’s earliest microblogging platform, was closed down for 16 months in 2009-10 after users posted information about riots in Urumqi, Xinjiang. Bill Bishop, Beijing-based editor of the Sinocism newsletter, tells CPJ that Sina rose to the top of the market both by building a great product and because, “it knew what it needed to do to stay in good graces with the government, unlike Fanfou.”

Microblog platforms use a variety of methods to comply with government censorship requests. Keyword filtering is the most widely deployed method to limit content. Some terms will prevent a post from being published at all; others will mark it for editorial review, while other terms cannot be searched through the platform’s search engine, making those posts difficult to access. China Digital Times researches and maintains lists of terms banned by Sina Weibo search and has collected almost 2,000 banned or temporarily banned search words since April 2011. In addition, Sina Weibo users often report that their posts have been published for only the author to see, so they may not realize at first that they have been censored.

If a user posts on a forbidden topic despite these filtering techniques, their account can be closed temporarily as a warning, or permanently for repeated offenses. According to an internal management notice from Sina that was leaked online, any “harmful” information that is posted must be deleted within five minutes, and posts by blacklisted users, who are still allowed to have an account, must be checked before publishing. Also, weibo service providers are required to give public security agencies access to their back end, through which officers can directly enter keywords that should be blocked and immediately delete videos and photos. Since his account was first closed in April 2012, Yang Haipeng has tried at least 65 times to reopen a Sina Weibo account with various coded user names, but each time his account has been closed.

According to a detailed exposé from Hong Kong-based Phoenix Weekly, which was widely distributed through Chinese cyberspace when it was published in March 2012, Sina has created a three-tier monitoring system, which works in tandem with the filtered keyword system described above. The first tier uses technology to search for banned keywords. The second tier uses personnel to manually review content before publishing, and transfer that information to the third tier. The staff on the third tier tracks current events to help the front end improve and update their banned keyword lists. Sina Chief Executive Charles Chao told Forbes in March 2011, that the company employs “at least 100” personnel to manually censor posts, but this is widely considered to be an underestimate.

Sina also has mechanisms in place for a targeted response to some incidents. According to the Phoenix report, Sina has a team of at least 600 people, all volunteers, who can be mobilized to respond to an emergency, such as the high-speed train crash in Wenzhou. This team includes Sina staff as well as former editors and temporary workers. Sina selects these “reserve forces” through open invitations to the Sina community and recruitment of weibo users who are generally “enthusiastic about network security and safety,” according to the Phoenix report. In other words, weibo users who actively post in support of the government’s Internet control policies and practices are rewarded by being asked to join the Sina team.

This corresponds with a new policy implemented by Sina in 2012, in which users reward or penalize fellow users with a point system. Users gain points for providing personal information, while points are deducted if a user distributes “false” information or makes personal attacks, according to a notice posted on Sina’s Weibo Community Management Center in May 2012. If a user’s point reserve reaches zero, his or her account is closed. But the definition of “false” information lies in the hands of the censors, who can use that term to define any politically unsavory posts.

This point system and a real-name registration system have both been inconsistently implemented. In December 2011, the Beijing Municipal Government issued rules requiring microblog services to collect and verify real name information by March 16, 2012, for all users who post publicly on their platform. The rules, if fully implemented, would impose a chill in online discussions, as much of the freedom of weibo platforms stems from users’ anonymity. However, Sina admitted that it had been unable to enforce the rule fully, “for reasons including existing user behavior, the nature of the microblogging product, and the lack of clarity on specific implementation procedures,” according to a company filing to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for fiscal year 2011. In the filing, Sina acknowledged that, “our noncompliance exposes us to potentially severe punishment by the Chinese government.” In December 2012, the National People’s Congress expanded rules for real-name registration to all companies that provide Internet access, including mobile phone companies.

Authorities also attempt to guide online conversations by employing large numbers of paid Internet commentators who post pro-government opinions on weibo and other online forums. Internet users have nicknamed these commentators the “fifty-cent party” for the fee they are rumored to be paid for each post. In the New Statesman in October 2012, artist and documentarian Ai Weiwei interviewed a member of the “fifty-cent party” who estimated that up to 20 percent of comments in online forums are written by paid commentators.

Weibo has created a new public sphere for Internet users in China—who tend to be urban, educated, middle- or upper-class citizens—that is changing the national conversation in significant ways. While users may chafe at the censorship, many realize that it is the price Sina pays for existing. Sinocism’s Bishop tells CPJ, “Yes, users get angry at Sina, in part as a proxy for anger at the government, but the sophisticated ones understand that Sina has already expanded the boundaries of discourse significantly and if they do not keep the government happy the service could be neutered or worse.”

Despite their obligations to government censors, Internet companies themselves find subtle ways to promote freedom of expression. In January 2013, a manager at Sina Weibo responded to criticism that his company had censored posts, explaining that even within the bounds of censorship, information can still be widely distributed before it is deleted. He wrote:

You are all crazily posting weibo, and those “little secretaries” are busily deleting them all. But with the situation as it is, has your ability to see this information been hindered? If they didn’t delete individual weibo posts, they would just directly shut down entire accounts. […] In fact, pressure already exists right when, and even before, a situation breaks out. But we can deal with it. The fact that all information can make it out represents a hard-fought victory in itself.

Siding with their users in promoting freedom of expression can, in some situations, provide a competitive advantage for companies. Sina Weibo closed down the account of prominent blogger and free speech advocate Isaac Mao, who had about 40,000 followers, in June 2012 after he criticized China’s space program as a waste of funds. Sina told him he had no recourse to appeal because the order had been given by “relevant authorities,” and was outside the company’s control. Subsequently, Tencent invited Mao to its microblog service, in what he told CPJ he believes was a move to one-up the competition. He currently has 10,000 followers on Tencent but is not as active there and acknowledges being more cautious after his experience with Sina.

For China’s journalists, weibo have provided an unprecedented platform to publish information that they cannot report in the traditional media, including censorship orders. China’s propaganda regime has traditionally strictly forbidden journalists from reporting on their orders, which are generally classified as state secrets. Shi Tao, a journalist in Hunan Province, was sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2005 after he transmitted online government propaganda orders. Now, reporters often post censorship directives online anonymously and they spread before censors can delete them. These leaked orders have become so common that Chinese Internet users have begun to refer to them as Directives from the Ministry of Truth, a reference to the propaganda department in George Orwell’s novel 1984. In turn, the term “Ministry of Truth” (真理部) is one of the most frequently deleted terms on weibo, according to researchers at Carnegie Mellon University.

Nevertheless, even on the strictly censored Chinese search engine Baidu, a search for the Chinese phrase “Ministry of Truth” will yield about 188,000 results. (China Digital Times collects and regularly translates into English Ministry of Truth Directives.)

Weibo have also empowered journalists to build solidarity in fighting censorship. In January 2013, journalists at the independent-minded Southern Weekly (also translated as Southern Weekend) in Guangzhou went on strike after local propaganda authorities unilaterally replaced the paper’s New Year greeting, which advocated constitutionalism and respect for rule of law, with a pro-government message. Angered by the censors’ excessive interference in their editing process, editors took to weibo to call for the dismissal of Tuo Zhen, the Guangdong provincial propaganda chief. In an unprecedented move, newspapers, individual journalists, and other Internet users around the country used their weibo accounts to rally support for Southern Weekly and speak out for press freedom. It soon became a major issue as movie stars and mainstream media posted both explicit and coded messages of support on their sites and weibo accounts.

As Internet users have access to more varied sources of news and information, the tone of discussions online has changed. Several years ago, the loudest and most dominant voice online in China belonged to the “angry youth,” as strident young nationalists are called. This shifted when other social issues moved to the forefront and as the Internet has increasingly allowed a broader spectrum of voices to be heard. Hu Yong, a prominent media professor at Beijing University, marks the changing point as 2008; as he wrote for China News Weekly in 2012, “nationalistic agendas have increasingly taken a back seat to agendas relating to popular welfare.” People now go online to find solidarity with other citizens who see problems in Chinese society—such as corruption, abuse of power, and environmental degradation—in their day-to-day lives. In his China News Weekly article, Hu wrote: “The winds have shifted. When your child cannot drink safe milk, cannot sit in a safe car, when you go out to dinner and are served ‘gutter oil,’ when the air in your city is hazy and gray and you don’t know the true PM2.5 [air quality] reading, you become more concerned with the direction Chinese society is taking and the problems of Chinese people’s happiness, rather than fighting another Boxer Rebellion [a violent anti-foreigner rebellion in 1900].” This was evident during the anti-Japan protests that raged through Chinese cities in September 2012 over disputed claims to the Diaoyu Islands. On the streets, government-sanctioned protests were heated and often violent as participants uniformly condemned Japan and even called for war. Online, the discussion was more multifaceted, with many Internet users taking a cynical view of the protests and the government’s role in encouraging them. One weibo user wrote: “Actually, my biggest question is, who in China owns the Diaoyu? It certainly isn’t me, and it certainly isn’t you. Maybe it’s ‘the people.’”

Internet users now feel much more empowered to counter official propaganda. Hu Xijin, the editor of the official Global Times, regularly uses his Sina Weibo account to post nationalistic, pro-government views. Each of his posts routinely receives hundreds, sometimes thousands, of comments harshly critical of his position. Regularly, as the government publishes its version of events surrounding an important issue, Internet users respond with their own views, often questioning the official information. Weibo users who scaled the Great Firewall to read and repost the daily air quality readings on the Twitter feed of the U.S. Embassy in Beijing began to loudly question the Chinese government’s statistics, which showed significantly less pollution. When Beijing declared the U.S. Embassy’s collection of air quality data illegal in June 2012, weibo users were outraged. The attention focused on this issue eventually helped to prod some Chinese cities to provide more accurate readings, and in January 2013, the government announced a website that would post air quality readings in 74 cities. Also that month, when record high levels of pollution blanketed northern and central China, Xinhua and other official media showed a shift in attitude on the issue by reporting in an unusually transparent manner on the levels of pollution, the causes, and the need for public oversight in finding solutions.

The shifting dynamic online does not change the fact that the Chinese government still does not allow a free press to report on issues of local and national importance. Without trusted, legitimate sources of news, the void is too often filled by unsubstantiated reports, half-truths, and rumors. In March 2012, the spread of rumors reached fever pitch when reports abounded that Bo Xilai’s allies in Beijing were staging a coup. With media forbidden from reporting on Bo’s situation, and international journalists prevented access to key figures, the public was left not knowing which reports they could trust.

In response, the government cracked down on the spreading of rumors, closing weibo accounts of those accused of spreading false information and arresting others. Sina and Tencent closed their comment functions for three days during this period (Chinese weibo platforms are more sophisticated than Twitter and allow comments on posts). Following the coup rumors, authorities closed 16 websites and detained six people, while an undisclosed number of people were “admonished and educated,” for spreading rumors, according to a report in the official People’s Daily. Capital Week financial magazine journalist Li Delin briefly disappeared around the same time after he reported on his weibo account of hearing gunfire in Beijing, according to Radio Free Asia. Since 2010, the government has launched regular campaigns to crack down on “false information” and rumors by closing websites. However, these campaigns often have broader targets. In an internal work order on limiting false news and information, issued by Dongzhi County Propaganda Department in Anhui Province in 2010, the orders were to “establish a specific monitoring system, following closely those influential, sensitive websites. For online false information, we need to discover them in a timely manner, accurately make judgments, handle them swiftly, and resolutely crack down on harmful information that attacks the Party and government and the news management system.” Under this order, any “sensitive” websites that are seen as criticizing the government could be targeted for closure.

As a new generation of leadership takes power in Beijing, they will rule over a citizenry that is far more informed, interconnected, and worldly than any of their predecessors. The Chinese people will no longer accept government propaganda as news, nor will they sit quietly when officials lie to them about issues that affect their lives. Yet the new leadership also possesses the world’s most sophisticated and powerful tools to control citizens’ access to information.

Rebecca MacKinnon, author of Consent of the Networked and a CPJ board member, has argued that rather than being a force that will topple the Communist Party, the Internet may in fact help prolong its rule. By allowing citizens a forum where they can discuss local issues, the country’s leaders both are given an opportunity to fix sources of widespread dissatisfaction while also giving citizens an outlet to vent frustrations so they will be less likely to demand political change. MacKinnon told The Wall Street Journal, “You have more give-and-take between government and citizens without the system having to change.”

Yet there is no doubt that access to the Internet, for those who can regularly go online in China, has had a profound impact on how people view the news and their government, and how they respond to injustices in their day-to-day lives. Already, before the new leadership even took the helm, the public knew far more about their new leaders than they have at any time in the past—information that censors have fought hard to keep hidden. Without weibo, the public may not yet know why Bo Xilai was removed from his post or his connection to Neil Heywood. What is publicly known about these recent scandals has likely only touched the surface of the whole story. But, as blogger and free speech advocate Mao told CPJ: “Weibo gave Chinese common people a chance to ‘know what they don’t know,’ even under fierce and ridiculous censorship practices.”

Sophie Beach is the executive editor of China Digital Times. She is a former senior Asia research associate at the Committee to Protect Journalists and received her master’s degree from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. She is based in Berkeley, Calif.