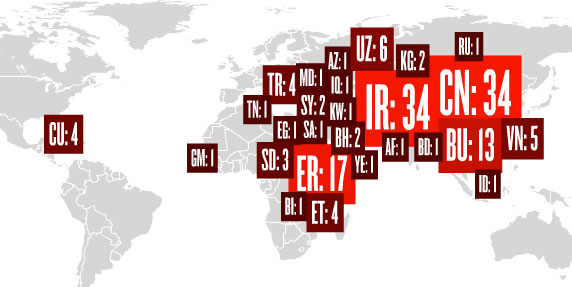

As of December 1, 2010 | » Read the accompanying report: “IRAN, CHINA DRIVE PRISON TALLY TO 14-YEAR HIGH”

Click on a country name to see summaries of individual cases.

Medium You need to upgrade your Flash Player

|

Charges You need to upgrade your Flash Player

|

Freelance / Staff You need to upgrade your Flash Player

|

Afghanistan: 1

Hojatullah Mujadadi, Radio Kapisa FM, Radio Television Afghanistan

Imprisoned: September 18, 2010

Afghan intelligence agents arrested Mujadadi in northeastern Kapisa province as he was covering the provincial governor’s visit to a voting station, news reports said. He was seized about the same time two other Afghan journalists were arrested by the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) on a vague accusation of Taliban links.

After an international outcry, ISAF issued a statement saying that all three were being released “without conditions,” but the Afghan National Directorate of Security did not free Mujadadi, according to multiple news reports.

Mujadadi had recently taken over as Radio Kapisa’s news director and had aggressively covered events throughout the province, where insurgent activity had been on the increase, according to news reports. No formal charges had been publicly disclosed by late year.

Azerbaijan: 1

Eynulla Fatullayev, Realny Azerbaijan and Gündalik Azarbaycan

Imprisoned: April 20, 2007

Authorities lodged a series of politically motivated criminal charges against Fatullayev, editor of the now-closed independent Russian-language weekly Realny Azerbaijan and the Azeri-language daily Gündalik Azarbaycan. The charges, which CPJ found to be fabricated, were filed after Fatullayev accused the government of a cover-up in the unsolved murder of his mentor, the editor Elmar Huseynov. In November 2009, CPJ honored Fatullayev with its International Press Freedom Award.

Authorities continued to hold Fatullayev in late year despite a March ruling by the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights, which ordered the journalist’s immediate release. The court found Azerbaijani authorities had violated Fatullayev’s rights to freedom of expression and fair trial. Azerbaijan appealed to the court’s Upper Chamber, which upheld the lower court in October. As a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights, Azerbaijan is bound to comply with rulings issued by the European Court.

Fatullayev was first charged in March 2007, after he published an in-depth piece that accused Azerbaijani authorities of ignoring evidence in Huseynov’s murder and obstructing the investigation. Fatullayev was charged initially with defaming Azerbaijanis in an Internet comment that the journalist said had been falsely attributed to him; he was sentenced to 30 months in prison in April 2007. Six months later, Fatullayev’s sentence was extended to eight and a half years on several other trumped-up charges, including terrorism, incitement to ethnic hatred, and tax evasion. The terrorism and incitement charges stemmed from a Realny Azerbaijan commentary that sharply criticized President Ilham Aliyev’s foreign policy regarding Iran. Fatullayev denied concealing income as the tax evasion charge alleged.

Just as the European Court’s deliberations on Fatullayev’s case were nearing an end, Azerbaijani authorities filed a new indictment. On December 30, 2009, they charged the editor with drug possession after prison guards claimed to have found heroin in his cell. Fatullayev said guards had planted the drugs while he was taking a shower. In July, a Garadagh District Court judge sentenced Fatullayev to another two and a half years in prison, a punishment not covered by the European Court ruling.

In November, the Azerbaijani Supreme Court ruled that the country would comply with the European Court’s decision, but Fatullayev remained imprisoned in late year based on the drug conviction. The drug charge was widely seen as a means by which authorities could continue to hold Fatullayev regardless of the European Court’s ruling. Based on Fatullayev’s account and authorities’ longstanding persecution of the editor, CPJ concluded that the drug charge was without basis.

Bahrain: 2

Abduljalil Alsingace, freelance

Imprisoned: August 13, 2010

Alsingace, a journalistic blogger and human rights activist, was arrested as part of a widespread government crackdown on political opponents, human rights defenders, and critical journalists ahead of October parliamentary elections.

The government sought to shield its actions from public scrutiny. On August 27, the public prosecutor issued a gag order barring journalists from reporting on the crackdown. Hundreds of people, mostly from the country’s Shiite majority, were arrested in the crackdown. Most were released, but the government put 23 prominent defendants on trial in October on multiple antistate charges.

Security agents detained Alsingace at Bahrain International Airport as he returned from London, where he had spoken about human rights violations in the kingdom, according to his lawyer, Mohamed Ahmed. Alsingace monitored human rights for the Shiite-dominated opposition Haq Movement for Civil Liberties and Democracy. Alsingace also wrote critically of the Bahraini government in articles published on his blog, Al-Faseela. Authorities briefly blocked local access to his blog in 2009.

Alsingace and other detainees said through their lawyers that they had been tortured in custody. In response to local and international concerns, Foreign Minister Sheikh Khaled bin al-Khalifa said his government would investigate the allegations, the Bahrain News Agency reported. No evident investigation had begun by late year.

Ali Abdel Imam, BahrainOnline

Imprisoned: September 5, 2010

Abdel Imam, a leading online journalist and the founder of the BahrainOnline news website, was arrested as part of broad government crackdown on political opponents, human rights defenders, and critical journalists ahead of October parliamentary elections.

The government sought to shield its actions from public scrutiny. On August 27, the public prosecutor issued a gag order barring journalists from reporting on the crackdown. Hundreds of people, mostly from the country’s Shiite majority, were arrested in the crackdown. Most were released, but the government put 23 prominent defendants on trial in October on multiple antistate charges.

BahrainOnline, which featured political news and commentary, had been blocked domestically since 2002 but was still widely read through proxy servers. The government shut its operations completely on the day Abdel Imam was arrested.

Bangladesh: 1

Mahmudur Rahman, Amar Desh

Imprisoned: June 1, 2010

Police raided the offices of the pro-opposition Bengali-language daily Amar Desh and arrested Rahman, a former opposition energy adviser and majority owner of the paper. Rahman, who was also serving as editor, was charged with unlawfully publishing the paper under an ex-employee’s name, local news reports said.

Dhaka Deputy Commissioner Muhibul Haque revoked Amar Desh’s publishing rights under the nation’s restrictive registration rules, causing the paper to close for about a month before the Supreme Court overturned the order and ruled the paper could reopen, according to an Amar Desh editor, Zahed Chowdhury.

Rahman obtained bail on the publishing charge but continued to be held on a number of other charges, including insult and defamation, that his supporters said were intended to suppress his critical journalism. During a court appearance on June 13, Rahman said police had blindfolded and beat him in custody, according to the local New Age newspaper. “On remand, he was seriously tortured and mistreated,” his lawyer said.

On August 10, the Supreme Court sentenced Rahman to six months in prison and fined him 100,000 taka (US$1,436) on charges of harming the court’s reputation. The charge stemmed from an April 21 Amar Desh article accusing the court of being biased in favor of the state, according to Agence France-Presse. Two colleagues were fined, and one served a month in prison, on the same charge, according to local news reports.

More than 20 defamation charges against Rahman, filed by members or allies of the ruling Awami League, including current energy adviser, Tawfik-e-Elahi Chowdhury, were pending in late year.

Burma: 13

Ne Min (Win Shwe), freelance

Imprisoned: February 2004

Ne Min, a lawyer and a former stringer for the BBC, was sentenced to 15 years in prison on May 7, 2004, on charges that he illegally passed information to “antigovernment” organizations operating in border areas, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners in Burma, a prisoner aid group based in Thailand.

It was the second time that Burma’s military government had imprisoned the well-known journalist, also known as Win Shwe, on charges related to disseminating information to news sources outside Burma. In 1989, a military tribunal sentenced Ne Min to 14 years of hard labor for “spreading false news and rumors to the BBC to fan further disturbances in the country” and “possession of documents including antigovernment literature, which he planned to send to the BBC,” according to official radio reports. He served nine years at Rangoon’s Insein Prison before being released in 1998.

Exiled Burmese journalists who spoke with CPJ said that Ne Min had provided news to political groups and exile-run news publications before his second arrest in February 2004.

Win Maw, Democratic Voice of Burma

Imprisoned: November 27, 2007

Win Maw, an undercover reporter for the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), was arrested with two friends by military intelligence agents in a Rangoon tea shop soon after visiting an Internet café. He was serving a 17-year jail sentence on charges related to his news reporting.

Authorities accused him of acting as the “mastermind” of DVB’s in-country news coverage of the 2007 Saffron Revolution, a series of Buddhist monk-led protests against the government that were put down by lethal military force, according to DVB.

Win Maw started reporting for DVB in 2003, one year after he was released from a seven-year prison sentence for composing pro-democracy songs, according to DVB. His video reports often focused on the activities of opposition groups, including the 88 Generation Students Group, according to DVB.

Win Maw was first sentenced in closed court proceedings to seven years in prison in 2008 for violations of the Immigration Act and sending “false” information to a Burmese exile-run media group. In 2009, he was sentenced to an additional 10 years for violations of the Electronic Act.

He was being held at the remote Thandwe Prison in northwestern Arakan state, nearly 600 miles from his Rangoon-based family. His family members alleged that police had tortured Win Maw during interrogations and denied him adequate medical attention.

Win Maw received the 2010 Kenji Nagai Memorial Award, an honor bestowed to Burmese journalists in memory of the Japanese photojournalist shot and killed by Burmese troops while covering the 2007 Saffron Revolution.

Nay Phone Latt (Nay Myo Kyaw), freelance

Imprisoned: January 29, 2008

Nay Phone Latt, also known as Nay Myo Kyaw, wrote a blog and owned three Internet cafés in Rangoon. He was arrested the morning of January 29, 2008, under the 1950 Emergency Provision Act on national security-related charges, according to news reports. His blog provided breaking news reports on the military’s crackdown on the 2007 Saffron Revolution, which were cited by several foreign news outlets, including the BBC. He also served as a youth member of the opposition National League for Democracy party, according to Reuters.

A court charged Nay Phone Latt in July 2008 with causing public offense and violating video and electronic laws when he posted caricatures of ruling generals on his blog, according to Reuters.

During closed judicial proceedings at Insein Prison on November 10, 2008, Nay Phone Latt was sentenced to 20 years and six months in prison, according to the Burma Media Association, a press freedom advocacy group, and news reports. The Rangoon Divisional Court later reduced the prison sentence to 12 years. Nay Phone Latt was transferred from Insein to Pa-an Prison in Karen state in late 2008, news reports said.

In 2010, he was honored with the prestigious PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award for his creative and courageous blog postings.

Sein Win Maung, Myanmar Nation

Imprisoned: February 15, 2008

A police raid on the offices of the weekly Myanmar Nation led to the arrest of editor Thet Zin and manager Sein Win Maung, according to local and international news reports. Police also seized the journalists’ cell phones, footage of monk-led antigovernment demonstrations that took place in Burma in September 2007, and a report by Paulo Sergio Pinheiro, U.N. special rapporteur for human rights in Burma, according to Aung Din, director of the Washington-based U.S. Campaign for Burma. The rapporteur’s report detailed killings associated with the military government’s crackdown on the 2007 demonstrators.

The New Delhi-based Mizzima news agency cited family members as saying that the two were first detained in the Thingangyun Township police station before being charged with illegal printing and publishing on February 25. On November 28, 2008, a closed court at the Insein Prison compound sentenced each to seven years in prison under the Printers and Publishers Registration Law, which requires that all publications be checked by a state censor before publication.

Police ordered Myanmar Nation’s staff to stop publishing temporarily, according to the Burma Media Association, a press freedom advocacy group with representatives in Bangkok. The exile-run news website Irrawaddy said the newspaper was allowed to resume publishing in March 2008; by October of that year, exile-run groups said, the journal had shut down for lack of leadership.

Thet Zin was among 7,000 prisoners released as part of a government amnesty on September 17, 2009, according to international news reports. Sein Win Maung remained behind bars in Kengtung Prison in Shan State, approximately 400 miles from his family in Rangoon.

Maung Thura (Zarganar), freelance

Imprisoned: June 4, 2008

Police arrested Maung Thura, a well-known blogger and comedian who used the professional name Zarganar, or “Tweezers,” at his home in Rangoon, according to news reports. The police also seized electronic equipment at the time of the arrest, according to Agence France-Presse.

Maung Thura had mobilized hundreds of entertainers to help survivors of Cyclone Nargis, which devastated Rangoon and much of the Irrawaddy Delta in May 2008. His footage of relief work in hard-hit areas was circulated on DVD and on the Internet. Photographs and DVD footage of the disaster’s aftermath were among the items police confiscated at the time of his arrest, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners in Burma and the U.S. Campaign for Burma.

In the week he was detained, Maung Thura gave several interviews to overseas-based news outlets, including the BBC, criticizing the military junta’s response to the disaster. The day after his arrest, state-controlled media published warnings against sending video footage of relief work to foreign news agencies.

During closed proceedings in August 2008 at Insein Prison in Rangoon, the comedian was indicted on at least seven charges, according to international news reports.

On November 21, 2008, the court sentenced Maung Thura to 45 years in prison on three separate counts of violating the Electronics Act. Six days later, the court added 14 years to his term after convicting him on charges of communicating with exiled dissidents and causing public alarm in interviews with foreign media, his defense lawyer, Khin Htay Kywe, told The Associated Press. The Rangoon Divisional Court later reduced the sentences to a total of 35 years.

The Electronics Act allows for harsh prison sentences for using electronic media, including the Internet, to send information outside the country without government approval.

Maung Thura had been detained on several occasions in the past, including a September 2007 episode in which he was accused of helping Buddhist monks during the Saffron Revolution protests, according to the exile-run press freedom group Burma Media Association. He had maintained a blog, Zarganar-windoor, detailing his work.

The Oslo-based Democratic Voice of Burma reported that Maung Thura was transferred in December 2008 to remote Myintkyinar Prison in Kachin state, where he was reported to be in poor health. His sister-in-law, Ma Nyein, told the exile news website Irrawaddy that the journalist suffered from hypertension and jaundice.

Zaw Thet Htwe, freelance

Imprisoned: June 13, 2008

Police arrested Rangoon-based freelance journalist Zaw Thet Htwe on June 13, 2008, in the town of Minbu, where he was visiting his mother, Agence France-Presse reported. The sportswriter had been working with comedian-blogger Maung Thura in delivering aid to victims of Cyclone Nargis and videotaping the relief effort.

The journalist, who formerly edited the popular sports newspaper First Eleven, was indicted in a closed tribunal on August 7, 2008, and was tried along with Maung Thura and two activists, AFP reported. The group faced multiple charges, including violating the Video Act and Electronic Act and disrupting public order and unlawful association, news reports said.

The Thailand-based Assistance Association for Political Prisoners in Burma said police confiscated a computer and cell phone during a raid on Zaw Thet Htwe’s Rangoon home.

In November 2008, Zaw Thet Htwe was sentenced to a total of 19 years in prison on charges of violating the Electronics Act, according to the Mizzima news agency. The Rangoon Divisional Court later reduced the term to 11 years, Mizzima reported. He was serving his sentence in Taunggyi Prison in Shan state.

The Electronics Act allows for harsh prison sentences for using electronic media to send information outside the country without government approval.

Zaw Thet Htwe had been arrested before, in 2003, and given the death sentence for plotting to overthrow the government, news reports said. The sentence was later commuted. AFP reported that the 2003 arrest was related to a story he published about a misappropriated sports grant.

Aung Kyaw San, Myanmar Tribune

Imprisoned: June 15, 2008

Aung Kyaw San, editor-in-chief of the Myanmar Tribune, was arrested in Rangoon along with 15 others returning from relief activities in the Irrawaddy Delta region, which was devastated by Cyclone Nargis, according to the Thailand-based Assistance Association for Political Prisoners in Burma and the Mizzima news agency.

Photographs that Aung Kyaw San had taken of cyclone victims appeared on some websites, according to the Burma Media Association, a press freedom group run by exiled journalists. Authorities closed the Burmese-language weekly after his arrest and did not allow his family visitation rights, according to the assistance association. On April 10, 2009, an Insein Prison court sentenced him to two years’ imprisonment for unlawful association, Mizzima reported.

Aung Kyaw San was formerly jailed in 1990 and held for more than three years for activities with the country’s pro-democracy movement, the association said. He was serving his sentence at the Taunggyi prison in Shan State, according to the association.

Ngwe Soe Lin (Tun Kyaw), Democratic Voice of Burma

Imprisoned: June 26, 2009

Ngwe Soe Lin, an undercover video journalist with the Oslo-based media organization Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), was arrested after leaving an Internet café in the old capital city of Rangoon, according to DVB. Before his conviction, DVB had publicly referred to him only as “T.”

He was one of two cameramen who took video footage of children orphaned by the 2008 Cyclone Nargis disaster for a documentary titled “Orphans of the Burmese Cyclone.” The film was recognized with a Rory Peck Award for best documentary in November 2009. DVB said that another video journalist, identified only as “Zoro,” went into hiding after Ngwe Soe Lin’s arrest.

On January 27, a special military court attached to Rangoon’s Insein Prison sentenced Ngwe Soe Lin, also known as Tun Kyaw, to 13 years in prison on charges related to the vague and draconian Electronics and Immigration acts, according to a DVB statement.

The Electronics Act allows for harsh prison sentences for using electronic media to send information outside the country without government approval.

Hla Hla Win, Democratic Voice of Burma

Myint Naing, freelance

Imprisoned: September 11, 2009

Hla Hla Win, an undercover reporter with the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), was arrested on her way back from a reporting assignment in Pakokku Township, Magwe Division, where she had conducted interviews with Buddhist monks in a local monastery. Her assistant, Myint Naing, was also arrested, according to the independent Asian Human Rights Commission.

Hla Hla Win was working on a story pegged to the second anniversary of the 2007 Saffron Revolution, Buddhist monk-led protests against the government that were put down by lethal military force, according to her DVB editors.

In October 2009, a Pakokku Township court sentenced Hla Hla Win and Myint Naing to seven years in prison for using an illegally imported motorcycle.

After interrogations in prison, Hla Hla Win was charged with violating the Electronics Act and sentenced to an additional 20 years on December 30, 2009. Myint Naing was sentenced to an additional 25 years under the act, the Asian Human Rights Commission said. The Electronics Act allows for harsh prison sentences for using electronic media to send information outside the country without government approval.

Hla Hla Win first joined DVB as an undercover reporter in December 2008. According to her editors, she played an active role in covering issues considered sensitive to the government, including local reaction to the controversial trial in 2009 of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

In 2010, Hla Hla Win received the Kenji Nagai Memorial Award, an honor bestowed to Burmese journalists in memory of the Japanese photojournalist shot and killed by Burmese troops while covering the 2007 Saffron Revolution.

Nyi Nyi Tun, Kandarawaddy

Imprisoned: October 14, 2009

A court attached to Rangoon’s Insein Prison sentenced Nyi Nyi Tun, editor of the news journal Kandarawaddy, to 13 years in prison on October 13, 2010, a year after his initial detention.

The court found Nyi Nyi Tun guilty of several antistate crimes, including violations of the Unlawful Associations, Immigration, and Wireless acts, according to Mizzima, a Burmese exile-run news agency.

Nyi Nyi Tun was first detained on terrorism charges on October 14, 2009, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners in Burma, a Thailand-based advocacy organization. Authorities originally tried to connect him to a series of bomb blasts in Rangoon but apparently dropped the allegations.

Nyi Nyi Tun told his family members that he had been tortured during his interrogation, Mizzima reported. After his arrest in 2009, Burmese authorities shut down Kandarawaddy, a local-language journal that operated out of the Kayah special region near the country’s eastern border, according to the Burma Media Association, a press freedom advocacy group.

Sithu Zeya, Democratic Voice of Burma

Imprisoned: April 15, 2010

Sithu Zeya, a video journalist with the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), was arrested while covering a grenade attack that left nine dead and hundreds injured during the annual Buddhist New Year water festival in Rangoon.

DVB editors said Sithu Zeya, 21, was near the crowded area where the blast occurred and started filming the aftermath as government authorities arrived on the scene. He was arrested immediately by police officials, who also seized his laptop computer and other personal belongings, DVB reported.

A police official, Khin Yi, said at a May 6 press conference that Sithu Zeya had been arrested for taking video footage of the attack. His mother, Yee Yee Tint, told DVB after a prison visit in May that he had been denied food and beaten during police interrogations that left a constant ringing in his ear.

DVB Deputy Editor Khin Maung Win told CPJ that Sithu Zeya had been forced to reveal under torture that his father, Maung Maung Zeya, also served as an undercover DVB reporter. They were both detained at Rangoon’s Insein Prison.

As of December 1, Sithu Zeya awaited a court verdict on charges related to the Unlawful Association, Immigration, and Electronic acts.

Maung Maung Zeya, Democratic Voice of Burma

Imprisoned: April 17, 2010

Maung Maung Zeya, an undercover reporter with the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), was arrested at his Rangoon house two days after his son and fellow DVB journalist, Sithu Zeya, was arrested for filming the aftermath of a fatal bomb attack during a Buddhist New Year celebration, according to DVB.

Maung Maung Zeya was first detained and interrogated at the Bahan Township police station in Rangoon and transferred June 14 to Rangoon’s Insein Prison. DVB editors said he was a “senior member” of their undercover team inside Burma and was responsible for operation management, including making reporting assignments to other DVB journalists.

Hearings in his trial on charges related to the Unlawful Association, Immigration, and Electronic acts began on June 22 at Western Rangoon’s Provincial Court. DVB Deputy Editor Khin Maung Win told CPJ that authorities had offered to free Maung Maung Zeya if he divulged the names of other undercover DVB reporters. Charges were pending as of December 1.

Burundi: 1

Jean-Claude Kavumbagu, Net Press

Imprisoned: July 17, 2010

Police arrested Kavumbagu, editor of the online news outlet Net Press, on treason charges stemming from commentary critical of the country’s security forces. The July 12 piece came a day after deadly twin bomb attacks in neighboring Uganda.

The hard-line Somali insurgency Al-Shabaab, which claimed responsibility for the Ugandan bombings, threatened more attacks if Uganda and Burundi did not withdraw military forces deployed in Somalia in support of the federal government there, according to news reports. Kavumbagu’s opinion piece questioned the ability of the Burundian security forces to prevent bomb attacks similar to those that struck Uganda.

Defense lawyer Gabriel Sinarinzi told CPJ that Kavumbagu was being held in pretrial detention at Mpimba Prison in Bugumbura. The charge could bring life imprisonment.

Kavumbagu had been imprisoned in 2008 on defamation charges related to an article critical of the amount of money spent on a presidential trip to the Beijing Olympics. That charge was eventually dismissed, Sinarinzi said.

China: 34

Xu Zerong (David Tsui), freelance

Imprisoned: June 24, 2000

Xu was serving a prison term on charges of “leaking state secrets” through his academic work on military history and “economic crimes” related to unauthorized publishing of foreign policy issues. Some observers believed that his jailing might have been related to an article he wrote for the Hong Kong-based Yazhou Zhoukan (Asia Weekly) magazine revealing clandestine Chinese Communist Party support for a Malaysian insurgency in the 1950s and 1960s.

Xu, a permanent resident of Hong Kong, was arrested in Guangzhou and held incommunicado for 18 months until trial. In December 2001, the Shenzhen Intermediate Court sentenced him to 13 years in prison; Xu’s appeal to Guangzhou Higher People’s Court was rejected in 2002.

According to court documents, the “state secrets” charges against Xu stemmed from his use of historical documents for academic research. Xu, also known as David Tsui, was an associate research professor at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies at Zhongshan University in Guangzhou. In 1992, he photocopied four books published in the 1950s about China’s role in the Korean War, which he then sent to a colleague in South Korea.

The verdict stated that the Security Committee of the People’s Liberation Army of Guangzhou determined that the books had not been declassified 40 years after being labeled “top secret.” After his arrest, St. Antony’s College at Oxford University, where Xu earned his doctorate and wrote his dissertation on the Korean War, was active in researching the case and calling for his release.

Xu was also the co-founder of a Hong Kong-based academic journal, Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Jikan (China Social Sciences Quarterly). The “economic crimes” charges were related to the “illegal publication” of more than 60,000 copies of 25 books and periodicals, including several books about Chinese politics and Beijing’s relations with Taiwan.

He was arrested just days before an article appeared in the June 26, 2000, issue of Yazhou Zhoukan, in which he accused the Communist Party of hypocrisy when it condemned countries that criticized China’s human rights record.

Xu began his sentence in Dongguan Prison, outside Guangzhou, but he was later transferred to Guangzhou Prison, where it was easier for his family to visit him. He was spared from hard labor and was allowed to read, research, and teach English in prison, according to the U.S.-based prisoner advocacy group Dui Hua Foundation. He suffered from high blood pressure and diabetes.

Dui Hua said Xu’s family members had been informed of sentence reductions that would move his scheduled release date to 2011. In 2009, the Independent Chinese PEN Center honored him with a Writers in Prison Award.

Jin Haike, freelance

Xu Wei, freelance

Imprisoned: March 13, 2001

Jin and Xu were among four members of an informal discussion group called Xin Qingnian Xuehui (New Youth Study Group) who were detained and accused of “subverting state authority.” Prosecutors cited online articles and essays on political and social reform as proof of their intent to overthrow the Communist Party leadership.

The two men, along with their colleagues, Yang Zili and Zhang Honghai, were charged with subversion on April 20, 2001. More than two years later, on May 29, 2003, the Beijing No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court sentenced Jin and Xu each to 10 years in prison, while Yang and Zhang each received sentences of eight years. All of the sentences were to be followed by two years’ deprivation of political rights.

The four young men were students and recent university graduates who gathered occasionally to discuss politics and reform with four others, including an informant for the Ministry of State Security. The most prominent in the group, Yang, posted his own thoughts, as well as reports by the others, on topics such as rural poverty and village elections, along with essays advocating democratic reform, on the popular website Yangzi de Sixiang Jiayuan (Yangzi’s Garden of Ideas). Xu was a reporter at Xiaofei Ribao (Consumer’s Daily). Public security agents pressured the newspaper to fire him before his arrest, a friend, Wang Ying, reported online.

The court cited a handful of articles, including Jin’s “Be a New Citizen, Reform China” and Yang’s “Choose Liberalism,” in the 2003 verdict against them. The Beijing High People’s Court rejected their appeal without hearing defense witnesses. Three of the witnesses who testified against the four men were fellow members of the group who later tried to retract their testimony.

Yang and Zhang were released on the expiration of their sentences on March 13, 2009, according to international news reports. Xu and Jin remained imprisoned at Beijing’s No. 2 Prison. Jin’s father told CPJ in October that his son’s health had improved. He had suffered from abdominal pain, for which he had undergone surgery in 2007. Xu was suffering from psychological stress while in prison, according to the Independent Chinese PEN Center.

Abdulghani Memetemin, freelance

Imprisoned: July 26, 2002

Memetemin, a writer, teacher, and translator who had actively advocated for the Uighur ethnic group in the northwestern Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, was detained in Kashgar, Xinjiang province, on charges of “leaking state secrets.”

In June 2003, the Kashgar Intermediate People’s Court sentenced Memetemin to nine years in prison, plus a three-year suspension of political rights. Radio Free Asia provided CPJ with court documents listing 18 specific counts against him, which included translating state news articles into Chinese from Uighur; forwarding official speeches to the Germany-based East Turkistan Information Center (ETIC)—a news outlet that advocated for an independent state for the Uighur ethnic group—and conducting original reporting for ETIC. The court also accused him of recruiting reporters for ETIC, which was banned in China.

Memetemin did not have legal representation at his trial.

Huang Jinqiu (Qing Shuijun, Huang Jin), freelance

Imprisoned: September 13, 2003

Huang, a columnist for the U.S.-based website Boxun News, was arrested in Jiangsu province, and his family was not notified of his arrest for more than three months. On September 27, 2004, the Changzhou Intermediate People’s Court sentenced him to 12 years in prison on charges of “subversion of state authority,” plus four years’ deprivation of political rights. The sentence was unusually harsh and appeared linked to his intention to form an opposition party.

Huang worked as a writer and editor in his native Shandong province, as well as in Guangdong province, before leaving China in 2000 to study journalism at the Central Academy of Art in Malaysia. While he was overseas, he began writing political commentary for Boxun News under the penname Qing Shuijun. He also wrote articles on arts and entertainment under the name Huang Jin. Huang’s writings reportedly caught the attention of the government in 2001. He told a friend that authorities had contacted his family to warn them about his writings, according to Boxun News.

In January 2003, Huang wrote in his online column that he intended to form a new opposition party, the China Patriot Democracy Party. When he returned to China in August 2003, he eluded public security agents just long enough to visit his family in Shandong province. In the last article he posted on Boxun News, titled “Me and My Public Security Friends,” he described being followed and harassed by security agents.

Huang’s appeal was rejected in December 2004. He was given a 22-month sentence reduction in July 2007, according to the U.S.-based prisoner advocacy group Dui Hua Foundation. The journalist, who suffered from arthritis, was serving his sentence in Pukou Prison in Jiangsu province.

Kong Youping, freelance

Imprisoned: December 13, 2003

Kong, an essayist and poet, was arrested in Anshan, Liaoning province. A former trade union official, he had written articles online that supported democratic reforms, appealed for the release of then-imprisoned Internet writer Liu Di, and called for a reversal of the government’s “counterrevolutionary” ruling on the pro-democracy demonstrations of 1989.

Kong’s essays included an appeal to democracy activists in China that stated, “In order to work well for democracy, we need a well-organized, strong, powerful, and effective organization. Otherwise, a mainland democracy movement will accomplish nothing.” Several of his articles and poems were posted on the Minzhu Luntan (Democracy Forum) website.

In 1998, Kong served time in prison after he became a member of the Liaoning province branch of the China Democracy Party (CDP), an opposition party. In 2004, he was tried on subversion charges along with co-defendant Ning Xianhua, who was accused of being vice chairman of the CDP branch in Liaoning, according to the U.S.-based advocacy organization Human Rights in China and court documents obtained by the U.S.-based Dui Hua Foundation. On September 16, 2004, the Shenyang Intermediate People’s Court sentenced Kong to 15 years in prison, plus four years’ deprivation of political rights. Ning received a 12-year sentence.

Kong suffered from hypertension and was imprisoned in the city of Lingyuan, far from his family. He received a sentence reduction to 10 years after an appeal, according to the Independent Chinese PEN Center. The group reported that his eyesight was deteriorating.

Shi Tao, freelance

Imprisoned: November 24, 2004

Shi, the former editorial director of the Changsha-based newspaper Dangdai Shang Bao (Contemporary Trade News), was detained near his home in Taiyuan, Shanxi province, in November 2004.

He was formally charged with “providing state secrets to foreigners” by sending an e-mail on his Yahoo account to the U.S.-based editor of the website Minzhu Luntan (Democracy Forum). In an anonymous e-mail sent several months before his arrest, Shi transcribed his notes from local propaganda department instructions to his newspaper, which included directives on coverage of the Falun Gong and the upcoming 15th anniversary of the military crackdown on demonstrators at Tiananmen Square.

The National Administration for the Protection of State Secrets retroactively certified the contents of the e-mail as classified, the official Xinhua News Agency reported.

On April 27, 2005, the Changsha Intermediate People’s Court found Shi guilty and sentenced him to a 10-year prison term. In June of that year, the Hunan Province High People’s Court rejected his appeal without granting a hearing.

Court documents in the case revealed that Yahoo had supplied information to Chinese authorities that helped them identify Shi as the sender of the e-mail. Yahoo’s participation in the identification of Shi and other jailed dissidents raised questions about the role that international Internet companies play in the repression of online speech in China and elsewhere.

In November 2005, CPJ honored Shi with its annual International Press Freedom Award for his courage in defending the ideals of free expression. In November 2007, members of the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs rebuked Yahoo executives for their role in the case and for wrongly testifying in earlier hearings that the company did not know the Chinese government’s intentions when it sought Shi’s account information.

Yahoo, Google, and Microsoft later joined with human rights organizations, academics, and investors to form the Global Network Initiative, which adopted a set of principles to protect online privacy and free expression in October 2008.

Human Rights Watch awarded Shi a Hellman/Hammett grant for persecuted writers in October 2009.

Zheng Yichun, freelance

Imprisoned: December 3, 2004

Zheng, a former professor, was a regular contributor to overseas news websites, including the U.S.-based Epoch Times, which is affiliated with the banned religious movement Falun Gong. He wrote a series of editorials that directly criticized the Communist Party and its control of the media.

Because of police warnings, Zheng’s family remained silent about his detention in Yingkou, Liaoning province, until state media reported that he had been arrested on suspicion of inciting subversion. Zheng was initially tried by the Yingkou Intermediate People’s Court on April 26, 2005. No verdict was announced and, on July 21, he was tried again on the same charges. As in the April 26 trial, proceedings lasted just three hours. Though officially “open” to the public, the courtroom was closed to all observers except close family members and government officials. Zheng’s supporters and a journalist were prevented from entering, according to a local source.

Prosecutors cited dozens of articles written by the journalist, and listed the titles of several essays in which he called for political reform, increased capitalism in China, and an end to the practice of imprisoning writers. On September 20, the court sentenced Zheng to seven years in prison, to be followed by three years’ deprivation of political rights.

Sources familiar with the case believe that Zheng’s harsh sentence may be linked to Chinese leaders’ objections to the Epoch Times series “Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party,” which called the Chinese Communist Party an “evil cult” with a “history of killings” and predicted its demise.

Zheng is diabetic, and his health declined after his imprisonment. After his first appeal was rejected, he intended to pursue an appeal in a higher court, but his defense lawyer, Gao Zhisheng, was himself imprisoned in August 2006. Zheng’s family was unable to find another lawyer willing to take the case.

In summer 2008, prison authorities at Jinzhou Prison in Liaoning informed Zheng’s family that he had suffered a brain hemorrhage and received urgent treatment in prison. However, no lawyer would agree to represent Zheng in an appeal for medical parole, according to Zheng Xiaochun, the journalist’s brother, who spoke with CPJ by telephone.

Yang Tongyan (Yang Tianshui), freelance

Imprisoned: December 23, 2005

Yang, commonly known by his penname Yang Tianshui, was detained along with a friend in Nanjing, eastern China. He was tried on charges of “subverting state authority,” and on May 17, 2006, the Zhenjiang Intermediate People’s Court sentenced him to 12 years in prison.

Yang was a well-known writer and member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He was a frequent contributor to U.S.-based websites banned in China, including Boxun News and Epoch Times. He often wrote critically about the ruling Communist Party, and he advocated for the release of jailed Internet writers.

According to the verdict in Yang’s case, which was translated into English by the U.S.-based Dui Hua Foundation, the harsh sentence against him was related to a fictitious online election, established by overseas Chinese citizens, for a “democratic Chinese transitional government.” His colleagues say that without his prior knowledge, he was elected to the leadership of the fictional government. He later wrote an article in Epoch Times in support of the model.

Prosecutors also accused Yang of transferring money from overseas to Wang Wenjiang, who had been convicted of endangering state security. Yang’s defense lawyer argued that this money was humanitarian assistance to the family of a jailed dissident and should not have constituted a criminal act.

Believing that the proceedings were fundamentally unjust, Yang did not appeal. He had already spent 10 years in prison for his opposition to the military crackdown on demonstrators at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

In June 2008, Shandong provincial authorities refused to renew the law license of Yang’s lawyer, press freedom advocate Li Jianqiang, who also represented imprisoned journalist Zhang Jianhong. In 2008, the PEN American Center announced that Yang was a recipient of the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award.

Zhang Jianhong, freelance

Imprisoned: September 6, 2006

The founder and editor of the popular news and literary website Aiqinhai (Aegean Sea) was taken from his home in Ningbo, in eastern China’s Zhejiang province. In October 2006, Zhang was formally arrested on charges of “inciting subversion.” He was sentenced to six years in prison by the Ningbo Intermediate People’s Court in March 2007, followed by one year’s deprivation of political rights.

Authorities did not clarify their allegations against Zhang, but supporters believed they were linked to online articles critical of government actions. An editorial he wrote two days before his detention called attention to international organizations’ criticism of the government’s human rights record and, in particular, to the poor treatment of journalists and their sources two years before the start of the Olympics. Zhang referred to the situation as “Olympicgate.”

Zhang was an author, screenwriter, and reporter who served a year and a half of “re-education through labor” in 1989-90 on counterrevolutionary charges for his writing in support of protesters. He was dismissed from a position in the local writers association and began working as a freelance writer.

His website, Aiqinhai, was closed in March 2006 for unauthorized posting of international and domestic news. He had also been a contributor to several U.S.-based Chinese-language websites, including Boxun News, the pro-democracy forum Minzhu Luntan, and Epoch Times.

In September 2007, Shandong provincial authorities refused to renew the law license of Zhang’s lawyer, press freedom advocate Li Jianqiang, who represented other imprisoned journalists as well.

Zhang’s health deteriorated significantly in jail, according to his wife, Dong Min, who spoke with CPJ by telephone in October 2008. He suffered from a debilitating disease affecting the nervous system and was unable to perform basic tasks without help. Appeals for parole on medical grounds were not granted and, by 2009, he was no longer able to write, according to the Independent Chinese PEN Center. His scheduled release date is September 2012.

Yang Maodong (Guo Feixiong), freelance

Imprisoned: September 14, 2006

Yang, commonly known by his penname Guo Feixiong, was a prolific writer, activist, and legal analyst for the Beijing-based Shengzhe law firm. Police detained him in September 2006 after he reported and gave advice on a number of sensitive political cases facing the local government in his home province of Guangdong.

Yang was detained for three months in 2005 for “sending news overseas” and disturbing public order after he reported on attempts by villagers in Taishi, Guangdong, to oust a village chief. He was eventually released without prosecution, but remained vocal on behalf of rights defenders, giving repeated interviews to foreign journalists. A police beating he sustained in February 2006 prompted a well-known human rights lawyer, Gao Zhisheng, to stage a high-profile hunger strike. Police in Beijing detained Yang for two days that February after he protested several government actions, including the closing of the popular Yunnan bulletin board, where he had posted information about the Taishi village case.

Yang’s September 2006 arrest was for “illegal business activity,” international news reports said. After a 15-month pretrial detention, a court convicted him of illegally publishing a magazine in 2001, according to U.S.-based advocacy groups. One of a series of magazines he had published since the 1990s, Political Earthquake in Shenyang, exposed one of the largest official graft cases in China’s history in Shenyang, Liaoning province, according to the Dui Hua Foundation. CPJ’s 2001 International Press Freedom Awardee, Jiang Weiping, spent five years in prison for reporting on the same case for a magazine in Hong Kong.

Although police had interrogated his assistant and confiscated funds in 2001 concerning the unauthorized publication charge, the case attracted no further punitive measures until Yang became involved in activism.

Yang’s defense team from the Mo Shaoping law firm in Beijing argued that a five-year limit for prosecuting illegal publishing had expired by the time of his trial, according to the Dui Hua Foundation, which published the defense statement in 2008. But Yang was still sentenced to five years in prison.

Yang has gone on hunger strike several times to protest ill treatment by authorities in Meizhou Prison in Guangdong. He was brutally force-fed on at least one of these occasions and remained in poor health, according to the advocacy group Human Rights in China (HRIC). The group said his treatment in the detention center before his trial was so aggressive that he attempted suicide. Police subjected him to around-the-clock interrogations for 13 days, HRIC said, and administered electric shocks. The group also said that Yang’s family had been persecuted since his imprisonment: His wife was laid off and his two children were held back in school in retribution for his work.

Sun Lin, freelance

Imprisoned: May 30, 2007

Nanjing-based reporter Sun was arrested along with his wife, He Fang, on May 30, 2007, according to the U.S.-based website Boxun News. Sun had previously documented harassment by authorities in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, as a result of his audio, video, and print reports for the banned Chinese-language news site. Boxun News said authorities confiscated a computer and video equipment from the couple at the time of their arrest.

In the arrest warrant, Sun was accused of possessing an illegal weapon, and a police statement issued on June 1, 2007, said he was the leader of a criminal gang. Lawyers met with Sun and He that June, but the couple was later denied visits from legal counsel and family members, according to a Boxun News report. A trial was postponed twice for lack of evidence.

A four-year prison sentence for possessing illegal weapons and assembling a disorderly crowd was delivered on June 30, 2008, in a hearing closed to Sun’s lawyers and family, according to The Associated Press.

Witness testimony about Sun’s possession of weapons was contradictory, according to news reports. The disorderly crowd charge was based on an incident in 2004, three years before his arrest. Police accused him of disturbing the peace while aiding people evicted from their homes, but the journalist said he had broken no laws.

Sun’s wife, He, was given a suspended sentence of 15 months in prison on similar charges, according to Sun’s defense lawyer, Mo Shaoping. She was allowed to return home after the hearing. The couple has a 12-year-old daughter.

Prison authorities transferred Sun to Jiangsu province’s Pukou Prison in September 2008, according to a report published by Boxun News. The report said Nanjing authorities refused to return the confiscated equipment. Because seeking a sentence reduction would involve admitting guilt, Sun has resolved to serve the time in full, according to the report.

Qi Chonghuai, freelance

Imprisoned: June 25, 2007

Qi and a colleague, Ma Shiping, criticized a local official in Shandong province in an article published June 8, 2007, on the website of the U.S.-based Epoch Times, according to Qi’s lawyer, Li Xiongbing. On June 14, the two posted photographs on Xinhua news agency’s anticorruption Web forum showing a luxurious government building in the city of Tengzhou.

Police in Tengzhou detained Ma on June 16 on charges of carrying a false press card. Qi, a journalist of 13 years, was arrested in his home in Jinan, the provincial capital, more than a week later, and charged with fraud and extortion, Li said. Qi was convicted and sentenced to four years in prison on May 13, 2008.

Qi was accused of taking money from local officials while reporting several stories, a charge he denied. The people from whom he was accused of extorting money were local officials threatened by his reporting, Li said. Qi told his lawyer and his wife, Jiao Xia, that police beat him during questioning on August 13, 2007, and again during a break in his trial. Qi was being held in Tengzhou Prison, a four-hour trip from his family’s home, which limited visits.

Ma, a freelance photographer, was sentenced in late 2007 to one and a half years in prison. He was released in 2009, according to Jiao Xia.

Lü Gengsong, freelance

Imprisoned: August 24, 2007

The Public Security Bureau in Hangzhou, capital of eastern Zhejiang province, charged Lü with “inciting subversion of state power,” according to human rights groups and news reports. Officials also searched his home and confiscated his computer hard drive and files soon after his detention in August 2007. Police did not notify his wife, Wang Xue’e, of the arrest for more than a month.

The detention was connected to Lü’s articles on corruption, land expropriation, organized crime, and human rights abuses, which were published on overseas websites. Police told his wife that his writings had “attacked the Communist Party,” she told CPJ. The day before his arrest, he reported on the trial and two-year sentence of housing rights activist Yang Yunbiao. Lü, a member of the banned China Democracy Party, was also author of a 2000 book, Corruption in the Communist Party of China, which was published in Hong Kong.

The Intermediate People’s Court in Hangzhou convicted Lü of subversion after a closed-door, one-day trial on January 22, 2008. The court handed down a four-year jail term the next month. The journalist’s wife, Wang Xue’e, told CPJ in October 2010 that she was able to visit Lü at Xijiao Prison in Hangzhou about once a month.

Hu Jia, freelance

Imprisoned: December 27, 2007

Police charged Hu, a prominent human rights activist and essayist, with “incitement to subvert state power” based on six online commentaries and two interviews with foreign media in which he criticized the Communist Party. On April 3, 2008, he was sentenced to three and a half years in prison.

Hu had advocated for AIDS patients, defended the rights of farmers, and promoted environmental protection. His writings, which appeared on his blog, criticized the Communist Party’s human rights record, called for democratic reform, and condemned government corruption. They included an open letter to the international community about China’s failure to fulfill pledges to improve human rights before the 2008 Olympics. He frequently provided information to other activists and foreign media to highlight human rights abuses in China.

Hu’s wife, human rights activist Zeng Jinyan, applied in April 2008 for medical parole for her husband, who suffered from chronic liver disease, but the request was turned down, according to updates posted on her blog, Liao Liao Yuan. The day of the Olympic opening ceremony in August 2008, Zeng was taken to the city of Dalian, Liaoning province, and only allowed to return to her Beijing home after 16 days. She reported this on her blog with no further explanation.

The European Parliament awarded Hu a prestigious human rights accolade, the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, in October 2008. The Chinese ambassador to the European Union warned that the prize would “bring serious damage to China-EU relations,” according to The Associated Press.

In October 2008, Hu was transferred to the Beijing Municipal Prison, according to Zeng’s blog. He raised human rights issues in jail, prompting security officials to cut off family visitation rights from November 2008 to February 2009, according to online news reports. Zeng reported that Hu’s health was deteriorating and that the prison did not have facilities to treat his liver condition.

Human Rights Watch awarded Hu a Hellman/Hammett grant for persecuted writers in October 2009.

Dhondup Wangchen, Filming for Tibet

Imprisoned: March 26, 2008

Police in Tongde, Qinghai province, arrested Wangchen, a Tibetan documentary filmmaker, shortly after he sent footage filmed in Tibet to colleagues, according to the production company, Filming for Tibet. A 25-minute film titled “Jigdrel” (Leaving Fear Behind) was produced from the tapes. Wangchen’s assistant, Jigme Gyatso, was also arrested, once in March 2008, and again in March 2009, after speaking out about his treatment in prison, Filming for Tibet said.

Filming for Tibet was founded in Switzerland by Gyaljong Tsetrin, a relative of Wangchen, who left Tibet in 2002 but maintained contact with people there. Tsetrin told CPJ that he had spoken to Wangchen on March 25, 2008, but that he had lost contact after that. He learned of the detention only later, after speaking by telephone with relatives.

Filming for the documentary was completed shortly before peaceful protests against Chinese rule of Tibet deteriorated into riots in Lhasa and in Tibetan areas of China in March 2008. The filmmakers had gone to Tibet to ask ordinary people about their lives under Chinese rule in the run-up to the Olympics.

The arrests were first publicized when the documentary was first shown in August 2008 before a small group of foreign reporters in a hotel room in Beijing on August 6. A second screening was interrupted by hotel management, according to Reuters.

Officials in Xining, Qinghai province, charged the filmmaker with inciting separatism and replaced the Tibetan’s own lawyer with a government appointee in July 2009, according to international reports.

On December 28, 2009, the Xining Intermediate People’s Court in Qinghai sentenced Wangchen to six years imprisonment on subversion charges, according to a statement issued by his family.

Wangchen was born in Qinghai but moved to Lhasa as a young man, according to his published biography. He had recently relocated with his wife, Lhamo Tso, and four children to Dharamsala, India, before returning to Tibet to begin filming, according to a report published in October 2008 by the South China Morning Post.

Tsetrin told CPJ that Wangchen’s assistant, Gyatso, was arrested on March 23, 2008. Gyatso, released on October 15, 2008, later described having been brutally beaten by interrogators during his seven months in detention, according to Filming for Tibet. The Dharamsala-based Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy reported that Gyatso was rearrested in March 2009 and released the next month.

Chen Daojun, freelance

Imprisoned: May 9, 2008

Police arrested Chen in Sichuan province shortly after he was involved in a “strolling” nonviolent protest against a proposed petrochemical plant in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, according to English- and Chinese-language news reports.

In November 2008, he was found guilty of inciting subversion against the state, according to international news reports. He was sentenced to three years in prison.

Prosecutors introduced three articles by Chen to demonstrate a purportedly anti-government stance, according to the Independent Chinese PEN Center. In one piece, an article for the Hong Kong-based political magazine Zheng Ming, Chen portrayed antigovernment protests in Tibet in a positive light. That article, first published in April 2008, was reposted on overseas websites. He also published an online article objecting to the Chengdu project, but it was not among the articles cited by the prosecution.

Huang Qi, 6-4tianwang

Imprisoned: June 10, 2008

The website 6-4tianwang reported that its founder, Huang, had been forced into a car along with two friends on June 10, 2008. On June 18, news reports said police had detained him and charged him with illegally holding state secrets.

In the aftermath of the Sichuan earthquake in May 2008, Huang’s website reported on the shoddy construction of schools that collapsed during the quake, killing hundreds of children, and on efforts to help victims of the disaster. His arrest came shortly after the site reported the detention of academic Zeng Hongling, who posted articles critical of earthquake relief on overseas websites.

Huang was denied access to a lawyer until September 23, 2008. One of his defense lawyers, Mo Shaoping, told reporters that Huang had been questioned about earthquake-related reports and photos on the website immediately after his arrest, but that the state secrets charge stemmed from documents saved on his computer. He said that his client was deprived of sleep during a 24-hour interrogation session after his June arrest.

Huang pleaded not guilty in closed proceedings at Chengdu Wuhou District Court on August 5, 2009. Police arrested a defense witness to prevent him from testifying on Huang’s behalf, according to the New York-based advocacy group Human Rights in China.

He was sentenced to three years in prison during a brief hearing in November 2009. The reason for the unusually drawn-out legal proceedings was not clear. Analysts speculated that it indicated the weakness of the case against Huang and disagreement among authorities as to the severity of the punishment.

Beginning in 2000, Huang had spent five years in prison on charges of inciting subversion in articles posted on his website.

Du Daobin, freelance

Imprisoned: July 21, 2008

Police rearrested Du during an apparent crackdown on dissidents before the Beijing Olympics in August 2008. His defense lawyer, Mo Shaoping, told CPJ that public security officials arrested the well-known Internet writer at his workplace in Yingcheng in the province of Hubei.

Du had been serving a four-year probationary term, handed down by a court on June 11, 2004, for inciting subversion of state power in articles published on Chinese and overseas websites. The probationary terms included reporting monthly to authorities and obtaining permission to travel. Alleging that he had violated the conditions, police revoked Du’s probation and jailed him, according to news reports.

Mo told CPJ in October 2008 that the defense team had sought to challenge the police decision, but Chinese law does not allow such appeals. Du was in Hanxi Prison in Wuhan, the provincial capital.

Mehbube Abrak (Mehbube Ablesh), freelance

Imprisoned: August 2008

Abrak, a state radio employee in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, was serving a three-year prison term for promoting “splittism,” according to information the Chinese government provided in June 2010 to the California-based human rights advocacy organization Dui Hua Foundation.

An employee of the advertising department of the state-run Xinjiang People’s Radio Station, she was removed from her post in August 2008 and imprisoned. Her colleagues told the U.S.-government funded Radio Free Asia that her imprisonment stemmed from articles criticizing the government that were posted on overseas websites. Radio Free Asia referred to her as Mehbube Ablesh.

Authorities imprisoned a number of journalists who covered ethnic unrest in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, a politically sensitive issue that is considered off-limits.

Liu Xiaobo, freelance

Imprisoned: December 8, 2008

Liu, a longtime advocate for political reform in China and the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was imprisoned for “inciting subversion” through his writing.

Liu was an author of Charter 08, a document promoting universal values, human rights, and democratic reform in China, and was among its 300 original signatories. He was detained in Beijing shortly before the charter was officially released, according to international news reports.

Liu was formally charged with subversion in June 2009, and he was tried in the Beijing Number 1 Intermediate Court in December of that year. Diplomats from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Sweden were denied access to the trial, the BBC reported. On December 25, 2009, the court convicted Liu of “inciting subversion” and sentenced him to 11 years in prison and two years’ deprivation of political rights.

The verdict cited several articles Liu had posted on overseas websites, including the BBC’s Chinese-language site and the U.S.-based websites Epoch Times and Observe China, all of which had criticized Communist Party rule. Six articles were named—including pieces headlined, “So the Chinese people only deserve ‘one-party participatory democracy?’” and “Changing the regime by changing society”—as evidence that Liu had incited subversion. Liu’s income was generated by his writing, his wife told the court.

The court verdict cited Liu’s authorship and distribution of Charter 08 as further evidence of subversion. The Beijing Municipal High People’s Court upheld the verdict in February 2010.

In October, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Liu its 2010 Peace Prize “for his long and nonviolent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.”

Kunchok Tsephel Gopey Tsang, Chomei

Imprisoned: February 26, 2009

Public security officials arrested Kunchok Tsephel, an online writer, in Gannan, a Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in the south of Gansu province, according to Tibetan rights groups. Kunchok Tsephel ran the Tibetan cultural issues website Chomei, according to the Dharamsala-based Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy. Kate Saunders, U.K. communications director for the International Campaign for Tibet, told CPJ by telephone from New Delhi that she learned of his arrest from two sources.

The detention appeared to be part of a wave of arrests of writers and intellectuals in advance of the 50th anniversary of the 1959 uprising preceding the Dalai Lama’s departure from Tibet in March. The 2008 anniversary had provoked ethnic rioting in Tibetan areas, and foreign reporters were barred from the region.

In November 2009, a Gannan court sentenced Kunchok Tsephel to 15 years in prison for disclosing state secrets, according to The Associated Press.

Kunga Tsayang (Gang-Nyi), freelance

Imprisoned: March 17, 2009

The Public Security Bureau arrested Kunga Tsayang during a late-night raid, according to the Dharamsala-based Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, which said it had received the information from several sources.

An environmental activist and photographer who also wrote online articles under the penname Gang-Nyi (Sun of Snowland), Tsayang maintained his own website titled Zindris (Jottings) and contributed to others. He wrote several essays on politics in Tibet, including “Who Is the Real Instigator of Protests?” according to the New York-based advocacy group Students for a Free Tibet.

Kunga Tsayang was convicted of revealing state secrets and sentenced in November 2010 to five years in prison, according to the center. Sentencing was imposed during a closed court proceeding in the Tibetan area of Gannan, Gansu province.

Several Tibetans, including journalists, were arrested around the March 10 anniversary of the failed uprising in 1959 that prompted the Dalai Lama’s departure from Tibet. Security measures were heightened in the region in the aftermath of ethnic rioting in March 2008.

Tan Zuoren, freelance

Imprisoned: March 28, 2009

Tan, an environmentalist and activist, had been investigating the deaths of schoolchildren killed in the May 2008 earthquake in Sichuan province when he was detained in Chengdu.

Tan, believing that shoddy school construction contributed to the high death toll, had intended to publish the results of his investigation ahead of the first anniversary of the earthquake, according to international news reports.

His supporters believe Tan was detained because of his investigation, although the formal charges did not cite his earthquake reporting. Instead, he was charged with “inciting subversion” for writings posted on overseas websites that criticized the military crackdown on demonstrators at Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989.

In particular, authorities cited “1989: A Witness to the Final Beauty,” a firsthand account of the events published on overseas websites in 2007, according to court documents. Several witnesses, including the prominent artist Ai Weiwei, were detained and blocked from testifying on Tan’s behalf at his August 2009 trial.

On February 9, 2010, Tan was convicted, and sentenced to five years in prison, according to international news reports. On June 9, 2010, Sichuan Provincial High People’s Court rejected his appeal.

Gulmire Imin, freelance

Imprisoned: July or August 2009

Imin was one of an unknown number of administrators of Uighur-language Web forums who were arrested after July 2009 riots in Urumqi, in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region.

In August 2010, Imin was sentenced to life in prison on charges of separatism, leaking state secrets, and organizing an illegal demonstration, a witness to her trial told the U.S. government-funded broadcaster Radio Free Asia.

Imin held a local government post in Urumqi. As a sidelight, she contributed poetry and short stories to the cultural website Salkin, and had been invited to help as a moderator in late spring 2009, her husband, Behtiyar Omer, told CPJ.

Authorities accused Imin of being an organizer of major demonstrations on July 5, 2009, and of using the Uighur-language website to distribute information about the event, Radio Free Asia reported. Imin had been critical of the government in her online writings, readers of the website told Radio Free Asia. The website was shut after the July riots and its contents were deleted.

She was also accused of leaking state secrets by phone to her husband, who lives in Norway. Her husband said he had called her on July 5 only to be sure she was safe.

The riots, which began as a protest of the death of Uighur migrant workers in Guangdong province, turned violent and resulted in the deaths of 200 people, according to the official Chinese government count. Chinese authorities shut down the Internet in Xinjiang for months after the riots as hundreds of protesters were arrested, according to international human rights organizations and local and international media reports.

Nureli, Salkin

Nijat Azat, Shabnam

Imprisoned: July or August 2009

Authorities imprisoned Nureli, who goes by one name, and Azat in an apparent crackdown on Uighur-language website managers. Azat was sentenced to 10 years and Nureli three years for endangering state security, according to international news reports. The precise dates of their arrests and convictions were not clear.

Their sites, which have been shut down by the government, had run news articles and discussion groups concerning Uighur issues. The New York Times cited friends and family members of the men who said they were prosecuted because they had failed to respond quickly enough when they were ordered to delete content that discussed the difficulties of life in Xinjiang.

Dilixiati Paerhati, Diyarim

Imprisoned: August 7, 2009

Paerhati, who edited the popular Uighur-language website Diyarim, was one of several online forum administrators arrested after ethnic violence in Urumqi in July 2009.

Paerhati was sentenced to a five-year prison term in July 2010 on charges of endangering state security, according to international news reports. He was detained and interrogated about riots in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region on July 24, 2009, but released without charge after eight days.

Agents seized Paerhati from his apartment on August 7, 2009, although the government issued no formal notice of arrest, his U.K.-based brother, Dilimulati, told Amnesty International. International news reports, citing his brother, said authorities had demanded Paerhati delete anti-government comments on the website.

Gheyrat Niyaz (Hailaite Niyazi), Uighurbiz

Imprisoned: October 1, 2009

Security officials arrested website manager Niyaz, sometimes referred to as Hailaite Niyazi, in his home in the regional capital, Urumqi, according to international news reports. He was convicted under sweeping charges of “endangering state security.”

According to international media reports, Niyaz was punished because of an August 2, 2009, interview with Yazhou Zhoukan (Asia Weekly), a Chinese-language magazine based in Hong Kong. In the interview, Niyaz said authorities had not taken steps to prevent violence in the July 2009 ethnic unrest that broke out in China’s far-western Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. At the time, media reports said about 200 people had been killed in the violence.

Niyaz, who once worked for the state newspapers Xinjiang Legal News and Xinjiang Economic Daily, also managed and edited the website Uighurbiz until June 2009. A statement posted on the website quoted Niyaz’s wife as saying that while he did give interviews to foreign media he had no malicious intentions.

Authorities blamed local and international Uighur sites for fueling the violence between Uighurs and Han Chinese in the predominantly Muslim Xinjiang region.

Uighurbiz founder Ilham Tohti was questioned about the contents of the site and detained for more than six weeks, according to international news reports.

Tashi Rabten, freelance

Imprisoned: April 6, 2010

Public security officials detained Rabten, a student at Northwest Minorities University in Lanzhou, according to Phayul, a pro-Tibetan independence news website based in New Delhi. No formal charges or trial proceedings had been disclosed by late year.

Rabten edited the magazine Shar Dungri (Eastern Snow Mountain) in the aftermath of ethnic rioting in Tibet in March 2008. The magazine was swiftly banned by local authorities, according to the International Campaign for Tibet. The journalist later self-published a collection of articles titled “Written in Blood,” saying in the introduction that “after an especially intense year of the usual soul-destroying events, something had to be said,” the campaign reported. The book and the magazine discussed democracy and recent anti-China protests; the book was banned after he had distributed 400 copies, according to the U.S. government-funded Radio Free Asia.

Rabten had been detained once before, in 2009, according to RFA and international Tibetan rights groups.

Dokru Tsultrim (Zhuori Cicheng), freelance

Imprisoned: May 24, 2010

A monk at Ngaba Gomang Monastery in western Sichuan province, Dokru Tsultrim was detained in April 2009 for alleged anti-government writings and articles in support of the Dalai Lama, according to the Dharamsala-based Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy and the International Campaign for Tibet. Released after a month in custody, he was detained again in May 2010, according to the Dharamsala-based Tibet Post International. No formal charges or trial proceedings had been disclosed by late 2010.

At the time of his 2010 arrest, security officials raided his room at the monastery, confiscated documents, and demanded his laptop, a relative told The Tibet Post International. He and a friend had planned to publish the writings of Tibetan youths detailing an April 2010 earthquake in Qinghai province, the relative said.

Dokru Tsultrim, originally from Qinghai province, which is on the Tibetan plateau, also managed a private Tibetan journal, Khawai Tsesok (Life of Snow), which ceased publication after his 2009 arrest, the center said. “Zhuori Cicheng” is the Chinese transliteration of his name, according to Tashi Choephel Jamatsang at the center, who provided CPJ with details by e-mail.

Buddha, freelance

Jangtse Donkho (Rongke), freelance

Kalsang Jinpa, freelance

Imprisoned: June and July 2010

The three men, contributors to the banned Tibetan-language magazine Shar Dungri (Eastern Snow Mountain), were detained in Aba, a Tibetan area in southwestern Sichuan province, the U.S. government-funded broadcaster Radio Free Asia (RFA) reported.

Jangtse Donkho, an author and editor who wrote under the penname Nyen, meaning Wild One, was detained on June 21, RFA reported. The name on his official ID is Rongke, according to the International Campaign for Tibet. Many Tibetans use only one name.

Buddha, a practicing physician, was detained on June 26 at the hospital where he worked in the town of Aba. Kalsang Jinpa, who wrote under the penname Garmi, meaning Blacksmith, was detained on June 19, the broadcaster reported, citing local sources.

On October 21, they were tried together in the Aba Intermediate Court. The charge was not disclosed, but a source told RFA that it may have been inciting separatism based on articles they had written in the aftermath of ethnic rioting in March 2008. No verdict had been disclosed in late year.

Shar Dungri was a collection of essays published in July 2008 and distributed in western China before authorities banned the publication, according to the advocacy group International Campaign for Tibet, which translated the journal. The writers assailed Chinese human rights abuses against Tibetans, lamented a history of repression, and questioned official media accounts of the March 2008 unrest.

Buddha’s essay, “Hindsight and Reflection,” was presented as part of the prosecution, RFA reported. According to a translation of the essay by the International Campaign for Tibet, Buddha wrote: “If development means even the slightest difference between today’s standards and the living conditions of half a century ago, why the disparity between the pace of construction and progress in Tibet and in mainland China?”

The editor of Shar Dungri, Tashi Rabten, was also jailed in 2010.

Cuba: 4

Pedro Argüelles Morán, Cooperativa Avileña de Periodistas Independientes

Imprisoned: March 18, 2003

The Cuban government freed 17 journalists arrested in the Black Spring crackdown of 2003, but four independent reporters and editors remained in prison when CPJ conducted its annual census on December 1.

Argüelles Morán was sentenced in April 2003 to 20 years in prison under Law 88 for the Protection of Cuba’s National Independence and Economy, which punishes anyone who commits acts “aiming at subverting the internal order of the nation and destroying its political, economic, and social system.”

Argüelles Morán, director of the independent news agency Cooperativa Avileña de Periodistas Independientes in the central province of Ciego de Ávila, was being held at the Canaleta Prison in his home province, his wife, Yolanda Vera Nerey, told CPJ. She said her husband, 62, had bone and respiratory ailments and cataracts in both eyes.

In July 2010, the Catholic Church brokered an agreement with Cuban authorities to release 52 political prisoners arrested in the 2003 crackdown. Spanish government officials also participated in the talks. The Cuban government did not explicitly demand that freed prisoners leave the country as a condition of release, but it’s clear that is what authorities wanted: All 17 of the reporters released as of December 1 were immediately exiled to Spain. (One later relocated to Chile.)