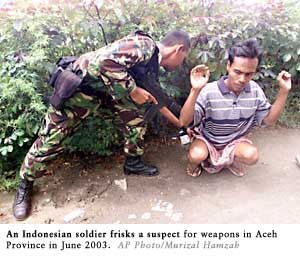

Borrowing a page from the U.S. playbook, the Indonesian military is restricting and controlling coverage of their war in the restive province of Aceh.

Aceh on the map

Jakarta, Indonesia, July 16, 2003–Journalists trained in combat awareness and embedded with military units. Daily press briefings detailing the latest government victories. Official appeals encouraging journalists to be patriotic. Strict controls preventing journalists from entering enemy territory.

Sound familiar? Yes, but this is not the war against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. It is Indonesia’s internal offensive against rebels in the far northern province of Aceh on the island of Sumatra, who are calling for an independent state. Taking a cue from U.S. relations with the media during the Iraq war, Indonesia has implemented a policy that keeps local journalists hemmed in and effectively bars foreign correspondents from the scene of the conflict.

The current military operation in Aceh is the largest staged by Indonesia since it seized East Timor, which was part of an island off the coast of Australia, in 1975. With 50,000 troops on the ground to combat some 5,000 guerrillas, the offensive began in mid-May in “shock and awe” fashion, with scripted parachute drops and fighter planes screaming across the skies for the television cameras. The government confidently proclaimed that the rebels of the Free Aceh Movement (known by the Indonesian acronym GAM) would be defeated in six months, marking an end to an insurgency that began in the mid-1970s. But the war is dragging on, casualty tolls are mounting, and less information than ever is coming out of Aceh.

The current military operation in Aceh is the largest staged by Indonesia since it seized East Timor, which was part of an island off the coast of Australia, in 1975. With 50,000 troops on the ground to combat some 5,000 guerrillas, the offensive began in mid-May in “shock and awe” fashion, with scripted parachute drops and fighter planes screaming across the skies for the television cameras. The government confidently proclaimed that the rebels of the Free Aceh Movement (known by the Indonesian acronym GAM) would be defeated in six months, marking an end to an insurgency that began in the mid-1970s. But the war is dragging on, casualty tolls are mounting, and less information than ever is coming out of Aceh.

The latest offensive in Aceh began on May 19, after peace talks were suspended, a six-month cease-fire ended, and the government declared martial law in the region. Since then, the Indonesian military has introduced progressively tougher restrictions and has issued pointed suggestions aimed at ensuring a compliant media. Local reporters are given a military training course before being embedded with combat units, just as reporters with U.S. troops were before the Iraq war. The domestic media have also been told that it is their duty as Indonesians to support the military effort.

As soon as the offensive began, military authorities ordered local press not to print GAM statements. According to the daily Jakarta Post, armed forces chief Gen. Endriartono Sutarto met with chief editors of major newspapers and broadcast outlets to rally support for the offensive. “In solving the Aceh case, public support plays a major role. If Indonesian media report news coming from GAM, we should question the depth of their nationalism,” Endriartono told reporters after the meeting. The military threatened newspapers that published early reports of military atrocities in the campaign with lawsuits, said the Jakarta Post.

Foreign reporters, meanwhile, have been kept well away from the action and, in recent weeks, have not even been allowed into the province at all.

“These regulations were sent to us by the U.S. Pacific Command. It is what they used in Iraq,” Maj. Gen. Sjafrie Sjamsuddin, chief of information for the Indonesian Armed Forces (known by the Indonesian acronym TNI), told foreign reporters at a press briefing here in the capital, Jakarta, on June 20 to formally unveil the tight regulations on foreign journalists trying to cover Aceh. “Of course, we have adapted them to our local environment.”

“These regulations were sent to us by the U.S. Pacific Command. It is what they used in Iraq,” Maj. Gen. Sjafrie Sjamsuddin, chief of information for the Indonesian Armed Forces (known by the Indonesian acronym TNI), told foreign reporters at a press briefing here in the capital, Jakarta, on June 20 to formally unveil the tight regulations on foreign journalists trying to cover Aceh. “Of course, we have adapted them to our local environment.”

Despite a generally free press since the ouster of former dictator Suharto in 1998, the Indonesian military’s implementation of U.S.-inspired policies has turned Aceh into one of the most restrictive places in the world for the press. Indonesia has a civilian government with some checks and balances, but Aceh is ruled solely by the military.

Major General Sjafrie, a Special Forces intelligence officer once implicated by U.N. investigators in crimes committed in East Timor during that territory’s bloody separation from Indonesia in 1999, said that the TNI’s chief aim was not only to protect journalists’ safety but also to prevent reporters from visiting GAM strongholds. “You are not allowed to go into GAM areas. That is the regulation. We are not going to permit reporters to enter those areas on purpose or accidentally, so don’t think of doing it,” he told reporters during the June 20 briefing.

Sjafrie said that foreign reporters are barred from being embedded with military units, and that the press must inform the military of all their movements in the province. In addition, reporters are prohibited from publishing “enemy propaganda.” Asked for clarification, he defined enemy propaganda as “trying to improve the GAM’s image in front of the public. That is not OK,” in news reports, he said.

In addition to military guidelines, reporters have to cope with other restrictions. Before going to Aceh, journalists must secure permission in writing from the Foreign Affairs Department. Once that letter is given, the Justice Department must grant another clearance. Only after journalists have these two documents can they fly to Aceh. Then, upon arrival, they must register with both the police and the military.

Authorities have also banned local television stations from selling footage to foreign agencies and have instructed local journalists not to share information with foreign colleagues–a rule that resurrects similar policies used by the Suharto regime to control the media.

As if all these restrictions were not enough, local military commanders have gotten into the act, toughening the various regulations. On June 26, Maj. Gen. Endang Suwarya, Aceh’s martial law administrator, issued a decree that all foreigners must enter and leave the province through Aceh’s capital, Banda Aceh, making it illegal for foreigners to travel by road in the region. He also banned all foreign visitors from traveling outside the capital and into other major cities.

As if all these restrictions were not enough, local military commanders have gotten into the act, toughening the various regulations. On June 26, Maj. Gen. Endang Suwarya, Aceh’s martial law administrator, issued a decree that all foreigners must enter and leave the province through Aceh’s capital, Banda Aceh, making it illegal for foreigners to travel by road in the region. He also banned all foreign visitors from traveling outside the capital and into other major cities.

The Jakarta Foreign Correspondents Club (JFCC) wrote a letter of complaint on June 26 to Indonesian officials about the mounting number of restrictions, stating that “a series of delays and constantly changing government and military rulings is in fact preventing foreign media access to Aceh.” The association noted that, despite numerous meetings with officials to try to work out a way to cover the story, regulations were making it extremely difficult. “We find it hard not to conclude that there is a concerted effort to permanently impose severe restrictions on foreign media from reporting on the integrated operation in Aceh,” the letter stated. As of this writing, the JFCC had received no response.

One reason things have gotten so tough may be military anger at one journalist who broke the rules. While Maj. Gen. Sjafrie was formally presenting the new press restrictions on June 20, American free-lance journalist William Nessen was traveling with GAM guerrillas in Aceh. Local military commanders were furious when they discovered that Nessen was in GAM territory. The military ordered Nessen to surrender, claiming that he was a GAM sympathizer and a spy for the rebels. Nessen denies the military’s charges. The journalist, who was accredited to write from Indonesia for the San Francisco Chronicle, told CPJ that he was writing a book about the Aceh conflict and gathering material for a documentary. Fearing for his life, however, Nessen turned himself over to Sjafrie and a U.S. Embassy representative on June 24. Indonesian authorities immediately arrested him, and he is now detained in Aceh on alleged immigration violations.

One reason things have gotten so tough may be military anger at one journalist who broke the rules. While Maj. Gen. Sjafrie was formally presenting the new press restrictions on June 20, American free-lance journalist William Nessen was traveling with GAM guerrillas in Aceh. Local military commanders were furious when they discovered that Nessen was in GAM territory. The military ordered Nessen to surrender, claiming that he was a GAM sympathizer and a spy for the rebels. Nessen denies the military’s charges. The journalist, who was accredited to write from Indonesia for the San Francisco Chronicle, told CPJ that he was writing a book about the Aceh conflict and gathering material for a documentary. Fearing for his life, however, Nessen turned himself over to Sjafrie and a U.S. Embassy representative on June 24. Indonesian authorities immediately arrested him, and he is now detained in Aceh on alleged immigration violations.

Other foreign journalists found in Aceh without permission are also subject to deportation and detention. Takaki Tadakomo, a 25-year-old Japanese free-lance photographer, was detained for two days in Aceh before the military sent him out of the province because he did not have official clearance to work in the area.

But there is certainly more to the restrictions than simple anger over one or two free-lancers. At stake, some believe, is Indonesia’s world image. The TNI already has a reputation for brutality earned during decades of internal conflicts and dictatorship in the country. The more that public scrutiny can be kept away from the battlefield–and away from potential human rights abuses–the less chance there is for widespread international condemnation of the current offensive.

And it is not only journalists who are being kept away from the area. Virtually all foreigners have been banned from visiting Aceh, and almost all humanitarian and nongovernmental organizations–foreign and local–have been forced to pull their staff out of the area, either because of the restrictions or due to security concerns.

Even diplomats must secure special permission to visit Aceh, so many embassies claim to have little direct information about what is happening with the war. “They aren’t letting us up there and they don’t tell us much,” said one senior diplomat in Jakarta.

It also appears that the lessons the TNI learned from the East Timor debacle are being applied in some ways in Aceh. In East Timor in 1999, the TNI used violent pro-Jakarta militias to attack and harass the press, especially in the days following a referendum in which voters chose to separate from Indonesia. Once the press, both foreign and local, was essentially driven out of East Timor, a scorched-earth policy went into effect, and the territory was looted or burned to the ground. To this day, almost no visual record of the destruction exists since the media were unable to operate there.

The latest restrictions are in stark contrast to the very early days of the current conflict, when it was fairly easy for the foreign press to enter Aceh and move with relative freedom around the province, despite the inherent danger of working in a war zone. Journalist Matthew Moore of the Sydney Morning Herald, for example, visited villages in Aceh in mid-May, just days after the offensive began, and related in graphic detail how local residents were being beaten and summarily executed on suspicion of being GAM rebels. In his May 25 story, “In Aceh, Death Has A Pattern,” Moore wrote that he found evidence of 13 men and two boys who appeared to have been summarily executed after being beaten. The military explanation for the killing was that a firefight with the rebels had occurred.

The latest restrictions are in stark contrast to the very early days of the current conflict, when it was fairly easy for the foreign press to enter Aceh and move with relative freedom around the province, despite the inherent danger of working in a war zone. Journalist Matthew Moore of the Sydney Morning Herald, for example, visited villages in Aceh in mid-May, just days after the offensive began, and related in graphic detail how local residents were being beaten and summarily executed on suspicion of being GAM rebels. In his May 25 story, “In Aceh, Death Has A Pattern,” Moore wrote that he found evidence of 13 men and two boys who appeared to have been summarily executed after being beaten. The military explanation for the killing was that a firefight with the rebels had occurred.

Moore, along with other members of the Jakarta press corps, has not received permission to return to Aceh. He now has to file stories with a Jakarta dateline. “In practice, since these regulations came out, no one is getting into Aceh,” says a Jakarta-based foreign correspondent. “So now covering the story is a hit-or-miss thing. You can’t rely on what the TNI says, and you can’t trust what GAM says either, and you can’t see for yourself.”

For Indonesian journalists, the dilemma is somewhat different but no less worrisome. Those covering the conflict as “embeds” are expected to get nearly all of their information from military sources. In exchange, reporters are given a seven-day military training course, allowed on limited military operations, and provided with security and housing in the field with the troops. Indonesian military officials have praised the policy, saying it has made the current Aceh war more transparent than any previous military operation. Some, however, say this is not a good policy for balanced journalism.

“This is a big debate among journalists now,” notes Eko Maryadi, director of advocacy for the Alliance of Independent Journalists in Jakarta (AJI). “It seems like it is putting us in the position of having to be on the side of the military.”

Many observers say that the war in Aceh is popular with the Indonesian public, who fear the breakup of their country and may still be stung by the loss of East Timor in 1999. “It is important to safeguard the territorial integrity of the state. [Indonesians] really believe that,” says Riza Primadi, the news director of TransTV. “So appeals to patriotism have an impact even on the media. A lot of [journalists] saw the occupation of East Timor as illegal, but Aceh has always been part of Indonesia. The Acehnese were leaders in our struggle against the Dutch. We do not want our country to disintegrate.”

Journalists in Jakarta say that direct pressure to be pro-military is consistent and hard to resist, especially for those embedded with military units. State Communications and Information Minister Syamsul Mu’arif, for example, told journalists recently that printing information from GAM rebels is unpatriotic. “We ask the media to be wise. Frankly, publishing statements from GAM will only hamper the [military] operation and alienate the TNI from the people,” he said, according to the Jakarta Post.

Journalists in Aceh are increasingly caught between the two sides and are at great risk of attack or worse. In several instances early in the campaign, unidentified gunmen shot at journalists as they drove through the province. On June 17, Jamaluddin (many Indonesians have only one name), a cameraman with state broadcaster TVRI, was found shot to death after having been kidnapped by unknown individuals shortly after the start of the offensive. The military blamed his death on GAM, a charge the rebels denied.

Meanwhile, Alif Imam Nurlambang, a reporter for Jakarta-based Radio 68H, reported that soldiers kicked and beat him on July 3 when he tried to interview a family of refugees in a rural village. “We are deeply concerned about the violence perpetrated by the security troops and strongly protest their uncontrolled, violent actions,” 68H’s director, Santoso, said in a statement.

GAM rebels have admitted to abducting a three-man crew of the TV network RCTI on June 29 on suspicion that they were too close to the military. But in a strange twist, military investigators have summoned journalists in Aceh for questioning about the abduction, saying they suspect that the crew was actually trying to report on GAM activities illegally.

The situation in Aceh looks set to be a protracted and messy guerrilla struggle. Last week, the military announced that the campaign against the rebels will likely continue much longer than the originally projected six months, leaving open the prospect that Indonesia’s fragile democracy may have a semi-permanent military regime acting within its borders for months, even years, to come.

The situation in Aceh looks set to be a protracted and messy guerrilla struggle. Last week, the military announced that the campaign against the rebels will likely continue much longer than the originally projected six months, leaving open the prospect that Indonesia’s fragile democracy may have a semi-permanent military regime acting within its borders for months, even years, to come.

With journalists subject to military pressure, and foreigners unable to travel in Aceh, learning anything of substance about the conflict, or about military actions against journalists, is almost impossible. And it is sobering to think that the inspiration for media manipulation and control in Aceh is the U.S. military policy in the Middle East.

“I can say that for the last several weeks, all the newspapers–or most anyway–and the TV are just quoting TNI, just carrying the TNI side,” says AJI’s Eko. “It is not sitting well with the journalists. They are all asking, ‘Why should we be patriotic? Why should we follow this crap policy from the United States that the TNI is using?'”

A Lin. Neumann is CPJ’s Asia program consultant. He is based in Bangkok, Thailand.