How Burmese journalism survives in one of the world’s most repressive regimes.

|

The ruling junta enforces obligatory and capricious censorship at every turn. A host of topics are off-limits, from heavy rainstorms to local politics, losing soccer matches to details of the World Trade Center attacks. But there is a strong literary tradition in Burma, and many living journalists and writers remember past freedoms and dream of better days to come. At the end of 2001, there were 12 journalists jailed for their work in Burma, according to CPJ research. The writers and editors who are still allowed to work must contend with a vast web of regulation and censorship imposed in the name of national security. Despite these challenges, certain courageous journalists within Burma and in the overseas Burmese community still manage to report the facts about their appalling government. On a recent visit to Burma, CPJ found surprising good humor and energy in a situation that would drive most reporters to despair. CPJ’s correspondent was welcomed by dozens of local journalists. Many had suffered harassment and jail time for their work. They risked their freedom just by talking to an international human rights organization. “Never mind, we are used to the threats,” said a retired newspaper editor who has spent years in prison during the last four decades. “If you haven’t been in jail you haven’t been a reporter here.” The impasse Modern Burma is deadlocked between pro-democracy forces on one side and the military regime on the other. Given strict censorship and government control over news content, it is virtually impossible for the Burmese people to engage in a frank national dialogue about their future.

The press restrictions put Suu Kyi herself at a marked disadvantage. If she hammers out a secret power-sharing deal with the junta, she and her allies will merely be perpetuating the undemocratic practices of the past 40 years. But government officials clearly fear that any crack in the façade of repression could lead to a reprise of the 1988 democratic uprising, which was brutally crushed by the current junta. Hence the general ban on domestic press coverage of the negotiations For the first time in years, however, state newspapers have been permitted to mention Suu Kyi without attaching ritual insults to her name. The official New Light of Myanmar, for example, no longer refers to Suu Kyi as an “evil tool of foreign interests.” The Myanmar Times, a new English-language weekly that is pitched mainly at foreign readers and maintains close links with Burmese military intelligence, has even been allowed to cover the releases of some political prisoners and the reopening of offices of Suu Kyi’s political party, the National League for Democracy. Operating outside the direct control of the Ministry of Information, the paper has been billed as evidence that the junta is becoming more tolerant of independent political speech. That is not the case. Most Burmese read neither the The Myanmar Times nor the handful of imported English-language publications available in Rangoon. For the vast majority of Burma’s people, the talks are just another rumor in the wind. They fear that the government is only raising expectations in order to undermine the opposition even further. “If we see some reality, then we will believe,” said the editor of one magazine. Past and present

In those days, Rangoon was a prosperous and fairly cosmopolitan Southeast Asian capital. Everything changed in 1962, when General Ne Win seized power and imposed the “Burmese Road to Socialism,” a policy designed to isolate the country from outside influences. One of his first moves was to nationalize all newspapers and establish a Press Scrutiny Board to impose strict censorship on all forms of information. The board remains fully active today. The current junta has made a few cosmetic changes since it seized power in 1988, notably by changing its name, in 1997, from the sinister-sounding State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) to the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC). A public relations offensive of sorts has been underway since then, largely directed by the Office of Strategic Studies (OSS), a think tank run by Lt. Gen. Khin Nyunt, head of military intelligence and effectively the junta’s third-ranking member. But the repressive mechanism remains essentially unchanged, and efforts to paint a picture of economic vitality under the new dispensation have not prospered. In March 2001, Khin Nyunt explained the regime’s press policy to an audience of Information Ministry staffers. “The staff should know the importance of the news value in line with the time and condition,” said the general, according to the New Light of Myanmar. “As the staff…are experienced persons in the journalism field, they have the ability to differentiate between the news which will benefit the nation and the people and the news which will have a bad effect on the nation and the people.” In practice, of course, this means that the regime sets the agenda, determines most news content, and only allows “safe” subjects to pass the censors. As a result, local journalists are reduced to writing tame lifestyle and business features for a range of anodyne weekly journals and monthly magazines. Occasionally, some try to push the envelope by inserting veiled political references into their copy. When their efforts are censored, they often pass manuscripts around to one another or share banned magazines they have managed to save from the scrap heap. “If we stop trying, there will soon be no journalism in Burma,” said an editor at a business magazine. A retired journalist who spent long years in prison, sacrificing health and career in the process, went out of his way to assist CPJ in meeting some of his colleagues and friends, a risky proposition in Burma. “I do this because this is what I can do,” he whispered. “They won’t let me write.” A younger journalist with a university degree in urban planning spent a long day driving CPJ’s reporter around Rangoon. “I want to show you what they’ve done to our people,” he explained as we passed through the drab outskirts of the city. About an hour outside the city center, he stopped at one of the “satellite towns” constructed after the anti-government uprising of 1988 as a way of emptying central Rangoon of the urban workers who helped swell the ranks of demonstrators. “There are no hospitals out here, few schools,” he said, adding that the inhabitants had been forcibly relocated. “There are very few factories and people have to queue for hours for buses into the city. People are sad. There is a lot of drinking.” Could he ever write about this? “I do,” he said as we drove slowly through the fetid squalor of a cramped shantytown carved out of a rice field. “In my private journal. I come here sometimes to talk with the people, but it is very dangerous for them to speak with outsiders. Anyway, it will never be published.” Meanwhile, he makes his living writing for a teen fashion magazine. Streets of terror

Numerous unofficial papers began appearing in mid-August as the uprising gathered steam and the military largely retreated behind closed gates. Even the doctrinaire state press joined the upheaval and started printing lively and uncensored reports. Amid the chaos, a quiet lady named Daw Aung San Suu Kyi returned from England to the country of her birth. The daughter of the country’s assassinated independence hero, Gen. Aung San, she quickly became a symbol swept up in the struggle for change. But instead of negotiating with the emerging democracy movement, another set of generals seized power. On September 18, the coup leaders announced the formation of a new junta called the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC)1 to replace Ne Win’s failed socialist regime. A maelstrom of killing ensued over the following days as machine guns swept the streets of protesters, leaving thousands of corpses in their wake. The underground and independent newspapers were immediately closed following the coup. Many of the journalists involved in Burma’s brief flirtation with press freedom fled to exile in neighboring Thailand or joined the underground resistance. Others were rounded up and jailed in the months and years following the crackdown. There was no independent Burmese press left to follow the story, and international media were largely transfixed by the Seoul Olympics. Fast forward

The freewheeling media debates of 1988 are long gone. They have been replaced by state newspapers such as the New Light of Myanmar, whose pages bristle with dour headlines about how Secretary Number One of the ruling junta met with the Fisheries Secretary to discuss the prawn industry. Opinion pages are frequently given over to multi-part diatribes against foreign reporters whose coverage is allegedly part of an elaborate global plot to besmirch the good name of the country. Other matters of national importance are also off limits. In the mid-1990s, the government conducted a sustained military offensive against several insurgent ethnic minority forces based in northern Burma. The local press ignored the story completely until the regime announced a series of negotiated settlements with purported minority representatives. Burma is a global center for the narcotics trade, but the problem is not covered except for government pronouncements. Former warlord Khun Sa is wanted for drug trafficking outside Burma. He is said to live in Rangoon, but the fact cannot be mentioned in the domestic press. A severe AIDS crisis is spreading rapidly, according to international experts, but there is little independent reporting allowed on the issue and all domestic coverage must follow the lead of the government. The issue of forced labor, which made Burma a virtual pariah state in the eyes of the International Labor Organization (ILO), is rarely a subject for media discussion, even though the junta is now allowing ILO representatives to monitor the issue. Outside information There is no public Internet access in Burma, apart from a handful of expensive e-mail accounts that pass through a central military server where messages can be delayed for hours while the censors read them. Fax machines must be licensed, and it can take years to obtain a permit to carry a cellular phone. State television is a joke. Satellite television is available in foreign homes and hotels, but few Burmese can afford it.

Ordinary people depend on Burmese-language broadcasts beamed into the country by Radio Free Asia, the VOA, the BBC, and the Democratic Voice of Burma, a dissident news service based in Norway. Hungry for news, people keep track of the world on tiny short wave receivers, hiding them from authorities and listening only in the privacy of their homes. Foreign journalists are generally barred from living in Burma. The international press corps in Rangoon consists of a single correspondent from the Chinese state news agency Xinhua. Foreign reporters must apply for special journalist visas to enter the country, along with a “Permit to Conduct Journalistic Activities.” The rules change unpredictably and there are no access guarantees. In recent months, perhaps because of the ongoing talks with Suu Kyi, some foreign correspondents have found it easier to enter Burma. The PR-savvy OSS has organized press junkets to Burma in order to promote tourism and publicize the regime’s drug control efforts. But all visiting reporters are followed and monitored by intelligence agents and it is almost impossible to interview Suu Kyi, who has been under house arrest for years. International journalists who write negative stories about Burma can be banned indefinitely. Bertil Lintner, a Thailand-based Swedish reporter for the Far Eastern Economic Review, has been unable to visit for fifteen years, although he is an internationally respected authority on Burma who has published several books on the country. A number of other Bangkok-based foreign correspondents are unable to obtain visas, perhaps because the regime thinks they know too much. Reporters who please the regime, on the other hand, have special access. “It is not a fair system,” said Aung Zaw, editor of the Burmese exile magazine The Irrawaddy, which is published in Thailand. “The government rewards the foreign journalists they like and punishes those who are too critical.” For years, much of the information from inside Burma has come from foreign embassies whose staffers can field phone calls from reporters abroad with relative security. International wire services must otherwise rely on Burmese stringers who operate under constant scrutiny. Wary of talking openly to CPJ for fear of government reprisals, a number of these reporters say they are regularly called in for questioning when their agencies run stories that are too critical of the regime. “It is a constant dance,” said one stringer. “We have to be very careful.” The reporters must frequently disguise their sources and plead ignorance on stories they write, especially when they cover human rights issues or anything concerning Aung San Suu Kyi. Overseas news editors sometimes change bylines on sensitive stories or add a Bangkok dateline in order to protect their colleagues inside Burma. Several Burmese stringers told CPJ that they can work sources inside the military government but must be very careful how they report the information. “Up there, among…the generals, there is difference of opinion,” said one wire agency stringer. “Sometimes we can get stories from them.” Burmese censors are extremely wary of bad news. The September 11 attacks were ignored by state television and only mentioned in passing by government newspapers. Police confiscated contraband videotapes of CNN’s September 11 coverage and threatened vendors with arrest. Even the news of junta leader Than Shwe’s letter of condolence to the United States was delayed by several days. When the national soccer team was eliminated from the regional Tiger Cup tournament in the early rounds in late 2000, the official censorship board quietly ordered newspapers to refrain from reporting the results. “We just enjoyed the trip. They wouldn’t let us do any work,” said a reporter who covered the tournament, which was held in Thailand. Others are less relaxed about the restrictions. “To me it is mental genocide. They are not killing the Burmese people physically but they are killing our ability to think,” said Pe Thet Nee, the editor of the Burmese Independent News Agency (BINA), a small exile news service that covers Burmese politics from Thailand. “It is a tragedy.” Voices of power

All four of Burma’s daily newspapers are published by the News and Periodicals Enterprise (NPE), a division of the Information Ministry. These dull rags are almost exclusively vehicles for government propaganda. In addition, some 50 private weekly and monthly magazines are allowed to exist under strict government supervision. It is a corrupt, Kafkaesque system in which journalists must do constant battle with the regime. “The censorship board has told us we must not write about AIDS, corruption, education, or the situation of students,” said the editor of a monthly magazine whose publishing license is held by a government ministry. “We also cannot write about any bad news and we must be careful about everything political. That does not leave very much for us to publish.” The only substantial change in censorship policy has been the gradual elimination, in the late 1990s, of the practice of inking out offending pages or ripping out whole sections of magazines. But the current system is hardly an improvement. Under laws dating back to the 1960s, each edition of every publication must be submitted in advance to the Press Scrutiny Board, an agency of the powerful Ministry of Information. If the censors object to any portion of a story, the entire layout must be redone to remove the offending material. Even after the censors have cleared the magazine, they must review all changes again after printing. Magazines must frequently scrap entire print runs because of last-minute objections from the censors. All this creates a powerful incentive toward self-censorship. The censorship process is also said to be rife with bribery. Censors must often be bribed to clear each new edition for publication. Publishers say they must also turn over up to 20 percent of each print run to the censors, who sell them on the street. One editor told CPJ that his magazine and others even had to pick up the tab for a Press Scrutiny Board holiday junket in 2000. “Even without the political problems, they are making money from us,” said the publisher of a beauty magazine. “Every time we turn around we have to pay.” Corruption and censorship notwithstanding, some outside observers see the emergence of semi-independent publications as a hopeful sign. “Burma is in transition from being…one of the most closed societies in the world,” said historian and Burma-watcher Martin Smith, who notes that business publications have “found a niche that didn’t exist before.” It is difficult to sustain even such tempered optimism in conversation with journalists inside the country. Two monthly business publications, Dana (Prosperity) and Myanmar Dana were launched in the 1990s as part of the regime’s drive to privatize state-owned industries and attract foreign investors. These publications are qualitatively among the best in Rangoon, but they operate within very narrow confines. “If we could report what we know, that would be one thing, but we can’t,” said one staffer. Under the radar

The board even spiked a local film critic’s review of The Man in the Iron Mask. Why? Because he quoted the Musketeer slogan, “One for all and all for one!” The censors apparently decided that “one” referred to Aung San Suu Kyi and “all” to the Burmese people. Tin Maung Than, the editor of the journal, Thintbawa (Your Life), fled into exile with his family in late 2000. Tin Maung Than got into trouble for circulating photocopies of a speech by a government official who criticized Burma’s economic policies. The military also watched him closely because he was once associated with Suu Kyi’s opposition political party, an affiliation he gave up many years ago to concentrate on writing. “Real journalism is not possible in Burma,” he told CPJ. “We have to say everything in general terms and let the readers feel the meaning for themselves.” Not much has changed since Tin Maung Than’s departure. During CPJ’s visit to Rangoon, one magazine was forced to delay publication after censors objected to a personal memoir that ran under the headline “Foolish Father, Foolish Daughter.” “They don’t like the word ‘foolish,'” explained the author of the story. “They think it shows disrespect for authority.” No bad news

International media reported the bare details of the disaster, but Burmese journalists mostly avoided it. However, one enterprising local reporter thought he had found a way to slip past the censors and into the story. He went to the flood area with his camera and notebook and documented relief efforts organized by the local people. “I took the angle that the Burmese people help one another in times of crisis and natural disaster,” the reporter recalled. “I didn’t say anything about the reason for the dam breaking or the maintenance problem.” Instead, he played up a spontaneous flood relief donation drive launched in Mandalay to help the victims and reflected on the Buddhist devotion that such charity implied. His editor showed me the layout that was sent to the censors. It was a 16-page photo essay, with dramatic pictures of the flood’s aftermath and quotes from survivors, a disaster story straight out of Journalism 101. But the public will never read it. “They censored it. I never got an explanation,” the writer said. That month, the magazine went to press 16 pages short of its normal length. And today, the censored article exists only in a handful of page proofs that were printed prior to the censor’s decision. “It is so silly,” said an editor. “What country does not have floods, accidents, natural disasters, conflicts? Yet they tell us that the image of the nation will suffer if we report these things.” More equal than others

With good color separation, quality paper, and a slick layout, The Myanmar Times is unlike any other publication sold on the streets of Rangoon. But the US$2 cover price is more than four times the cost of any other weekly journal and well beyond the means of most Burmese readers. A recently launched Burmese language version is also expensive in local terms. The Myanmar Times is exempt from many of the rules that govern other publications in Rangoon, a fact that annoys its competitors no end. For example, the Times is the only Burmese paper to have carried fairly straight coverage of the ongoing talks between Aung San Suu Kyi and members of the ruling junta. On occasion, Suu Kyi’s picture even appears on the inside pages of the paper. The Myanmar Times is also the only local paper to have mentioned recent releases of political prisoners and to have noted that the ILO recently accused the Burmese military of using forced labor in rural areas. Dunkley plugs his new weekly as the first “truly free press” in recent Burmese history. In fact, Dunkley’s enterprise is the brainchild of intelligence chief Lt.-Gen. Khin Nyunt, Secretary Number One of the ruling junta, and members of the Office of Strategic Studies (OSS), the government think tank over which he presides. Earlier this year, the Times even carried a rare interview with Khin Nyunt. The Myanmar Times is a key part of Khin Nyunt’s strategy to rehabilitate the battered international image of the military junta, says The Review’s Bertil Lintner, who has covered Burmese affairs for 20 years. Lintner and other analysts believe that Khin Nyunt disagrees with the Information Ministry’s heavy-handed approach to propaganda. An influential OSS officer named Col. Thein Swe is frequently quoted in The Myanmar Times and appears to be actively involved in running the paper. When the Times was launched, Thein Swe told Asiaweek that the paper would be “different, more flexible” than other papers. For his part, Dunkley downplays his paper’s obvious closeness to the regime. “Officially we go through military scrutiny, but the reality is that we have an amicable dialogue, and 95 percent [of the paper] is not subject to censorship,” Dunkley told Agence France-Presse earlier this year. “I just report the facts,” he added. When reached by phone in Rangoon, Dunkley refused to speak with a CPJ reporter. He referred all questions to an assistant who subsequently could not be reached despite repeated calls. The cost The net effect of years of isolation and censorship has been to starve the Burmese people of news access that is taken for granted in most countries. By comparison, even China is an open society despite its heavy-handed system of media control. As the world moves ever faster toward a more open global information society, the people of Burma are stuck in the past. Many of the social and political problems that plague Burma–ethnic tensions, rampant corruption, poverty–are worsened by the lack of information and debate on the issues. The regime apparently fears that any media liberalization could provoke a political transition in which it would risk loss of power and subsequent reprisals. Whatever happens to the current regime, one lasting legacy of military rule will be the generals’ steadfast opposition to press freedom. For almost 40 years, ever since Ne Win staged his coup in 1962, the country has been run as the parochial playground of whatever band of officers is in power, with the result that not only the financial capital but also the intellectual capital of the country has been depleted. It will be a long time in recovery. “If we were allowed to, we could set up newspapers tomorrow because we have the presses,” said a frail former editor who once spent seven years in solitary confinement because of his newspaper work. “But where would we find the journalists? I am one of the last…who remembers what it was like to have real newspapers in this country.” |

|

In Thailand, exiled Burmese journalists struggle to report on their own country. Mae Sot, Thailand–The Burma Border Press Club is in session tonight at an empty, dimly lit Chinese restaurant in this dusty trading town near the Burmese border. At the table, six reporters are eagerly discussing their work. These journalists, five men and one woman, most of them former political activists exiled now in Thailand, are stringers for wire agencies and Burmese language short-wave radio services. They cover ongoing ethnic rebellions along the border, as well as the thousands of Burmese refugees inside Thailand. The task is daunting. Some 100 Burmese exiles are now working as journalists along the Thai-Burmese border. Their reports form the basis for news items that are then beamed back into Burma by the BBC, VOA, Radio Free Asia, and the Oslo-based Democratic Voice of Burma, via short-wave radio. It is illegal and dangerous for these journalists to enter Burma. If they sneak in, they face possible arrest. Burmese military intelligence agents are believed to operate inside Thai border towns and refugee camps. Thai military intelligence agents routinely monitor the activities of these journalists, checking their papers, milking them for information, and sometimes threatening them with deportation. Exiled Burmese political leaders also exert pressure on reporters, trying to enforce their own version of political correctness on coverage of news from across the border. “We have to be afraid of the Thai authorities, the Burmese authorities and the rebel authorities,” says Win Myint, a BBC stringer based in Mae Sot. These émigré reporters are among the very few news professionals who are able to obtain reasonably accurate information about the ethnic insurgencies inside Burma. The reporters interview Burmese refugees, migrant workers, and traders who move between the two countries. Occasionally, they even take daring jaunts across the border. Exiled Burmese journalists are denied both Thai passports and political refugee status. Thai authorities tolerate the Burmese journalists but refuse to grant them legal status for fear of offending the Burmese junta. During periods of political tension–as in 2000, when a band of Burmese rebels attacked a Thai hospital and briefly took the staff hostage–the journalists face harassment and possible deportation. The English-language magazine The Irrawaddy has built an international reputation since it began about ten years ago as a newsletter in the Thai living room of its editor, Aung Zaw. Now operating out of a substantial office in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai, The Irrawaddy hopes to become an independent national news magazine in Burma once the military regime is gone. “Our goal is always to go back home,” said Aung Zaw, a one-time student activist who fled to Thailand following the 1988 pro-democracy uprising. Other exile publications have a narrower focus. The Shan Herald Agency for News (SHAN), for example, grew out of the struggle for independence inside the Shan State in northern Burma. When Khun Sa, a drug lord who was the main Shan military leader, struck a deal with the Burmese junta in 1996, many other Shan who remained committed to the independence struggle were forced into exile. Relying on informants inside the Shan State, SHAN puts out Independence, a monthly magazine that focuses on Shan community issues, including the surviving Shan rebel groups. “Outside of our community, people know very little about the Shan,” said Khun Sai, the editor of Independence. “We want to increase awareness. We believe that in order to become free and democratic, we need a free press.” Similar publications cover the Karen community inside Burma, the only ethnic group that has not yet struck a deal with the junta. There are also newsletters tied to the National League for Democracy, Aung San Suu Kyi’s opposition political party, and to exiled student groups. The National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma, a shadow government in exile with links to the political opposition, puts out its own newsletters. Most of these groups try to distribute their publications inside Burma, although just being caught reading one of these newsletters can result in a lengthy jail sentence. Independence, which publishes in both Burmese and Shan, claims to circulate 500 of its 2,000 copies a month inside the country, but editors say it is risky even to get the paper across the border. The publications must patch their funding together from international donors whose priorities are constantly shifting. Most publications operate on a hand to mouth basis. It is tough work, performed by dedicated reporters, most of whom could seek an easier life by applying for political asylum in the West. “We have no place to go,” said VOA stringer Aye Aye Mar, one of the few women journalists working on the border. “But we are here to be journalists and we want to work on the border. We want to stay as close as we can to our country.” –A. Lin Neumann |

|

A. Lin Neumann is CPJ’s Asia consultant, based in Bangkok, Thailand. He was one of only four foreign journalists who were actually in Rangoon when the pro-democracy uprising was brutally crushed in September 1988. Many of the names in this report have been changed for the protection of those who dared speak freely. |

Rangoon–The most surprising thing about the Burmese press is that it still exists. Governed repressively since 1962 and currently under military rule, Burma is by far the most information-starved country in Southeast Asia. And yet the press refuses to die.

Rangoon–The most surprising thing about the Burmese press is that it still exists. Governed repressively since 1962 and currently under military rule, Burma is by far the most information-starved country in Southeast Asia. And yet the press refuses to die. In 2001, for example, the local press barely commented on closed-door talks–the first since 1994–between the regime and opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The United Nations-brokered negotiations were widely covered everywhere except Burma. “We have no idea about this,” said one local journalist. “The talks cannot be discussed.”

In 2001, for example, the local press barely commented on closed-door talks–the first since 1994–between the regime and opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The United Nations-brokered negotiations were widely covered everywhere except Burma. “We have no idea about this,” said one local journalist. “The talks cannot be discussed.” For a time, starting with independence from Britain in 1948 and ending when the military seized power in 1962, Burma enjoyed a fair measure of press freedom. Literary journals, mass market dailies, and political party newspapers competed freely for readers. It was a tumultuous period in which competing ideologies vied for popular support.

For a time, starting with independence from Britain in 1948 and ending when the military seized power in 1962, Burma enjoyed a fair measure of press freedom. Literary journals, mass market dailies, and political party newspapers competed freely for readers. It was a tumultuous period in which competing ideologies vied for popular support. In 1988 there was a popular uprising against the semi-socialist dictatorship of General Ne Win. The streets were filled with thousands of young demonstrators calling for democracy. The demonstrators formed street committees to try and govern a capital that had seemingly been abandoned by its government. Official buildings had been ransacked and the bureaucracy was at a standstill. Even customs and immigration officials were scarcely at their posts.

In 1988 there was a popular uprising against the semi-socialist dictatorship of General Ne Win. The streets were filled with thousands of young demonstrators calling for democracy. The demonstrators formed street committees to try and govern a capital that had seemingly been abandoned by its government. Official buildings had been ransacked and the bureaucracy was at a standstill. Even customs and immigration officials were scarcely at their posts. More than thirteen years later, Rangoon remains a city out of time. The stunning Shwedagon Pagoda complex still glistens magically in the sun and the charmingly faded British colonial skyline has changed little. A handful of new buildings rose in the mid 1990s to herald Burma’s planned debut as an Asian economic tiger. A few new hotels were built or refurbished to cater to a tourist wave that never landed. The splendid century-old Strand Hotel, which was a shadow of its Victorian grandeur in 1988, has been restored to its original glory. But the occupancy? “None sir,” said the bellman with a sad nod of the head. “No guests this week, sir.” The elegant lobby bar only buzzes when the small diplomatic community gathers to swap rumors on Friday evening.

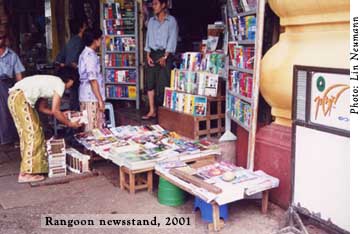

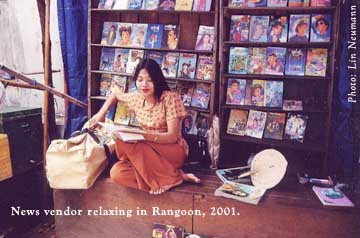

More than thirteen years later, Rangoon remains a city out of time. The stunning Shwedagon Pagoda complex still glistens magically in the sun and the charmingly faded British colonial skyline has changed little. A handful of new buildings rose in the mid 1990s to herald Burma’s planned debut as an Asian economic tiger. A few new hotels were built or refurbished to cater to a tourist wave that never landed. The splendid century-old Strand Hotel, which was a shadow of its Victorian grandeur in 1988, has been restored to its original glory. But the occupancy? “None sir,” said the bellman with a sad nod of the head. “No guests this week, sir.” The elegant lobby bar only buzzes when the small diplomatic community gathers to swap rumors on Friday evening. Tattered copies of foreign newsmagazines are sold as virtual contraband from street stalls. For a premium, passing motorists can also buy smuggled week-old copies of the Bangkok Post and the Nation, both English dailies from neighboring Thailand. The papers are hawked by skittish newsboys who keep a watchful eye out for the police.

Tattered copies of foreign newsmagazines are sold as virtual contraband from street stalls. For a premium, passing motorists can also buy smuggled week-old copies of the Bangkok Post and the Nation, both English dailies from neighboring Thailand. The papers are hawked by skittish newsboys who keep a watchful eye out for the police. Private publications operate under a Byzantine regulatory framework. To obtain a publishing license, which can be revoked at any time, they must pay stiff fees (as well as bribes) to government agencies such as the Department of the Navy and the Drug Control Board. The licensing agencies generally appoint officials as nominal chief editors.

Private publications operate under a Byzantine regulatory framework. To obtain a publishing license, which can be revoked at any time, they must pay stiff fees (as well as bribes) to government agencies such as the Department of the Navy and the Drug Control Board. The licensing agencies generally appoint officials as nominal chief editors. The July 2001 issue of a journal called Sabai Phyu (White Jasmine) featured a cover quote from the Western social theorist Edward de Bono: “You can analyze the past, but you must design the future. Otherwise it may be no better than the past.” One editor said the quote probably escaped censorship only because the censors didn’t understand what it meant. The editor of a fashion magazine told CPJ that the list of banned topics he had encountered included everything from deposed dictators such as Slobodan Milosevic of Yugoslavia and Suharto of Indonesia to floods, plane crashes, and train wrecks. Staffers knew not to write anything even remotely critical about the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the ten-member regional alliance that Burma joined in 1997. “We are encouraged, though, to write anything bad about Thailand,” said the editor, noting that the two countries are currently embroiled in a border dispute. “But that could also change.”

The July 2001 issue of a journal called Sabai Phyu (White Jasmine) featured a cover quote from the Western social theorist Edward de Bono: “You can analyze the past, but you must design the future. Otherwise it may be no better than the past.” One editor said the quote probably escaped censorship only because the censors didn’t understand what it meant. The editor of a fashion magazine told CPJ that the list of banned topics he had encountered included everything from deposed dictators such as Slobodan Milosevic of Yugoslavia and Suharto of Indonesia to floods, plane crashes, and train wrecks. Staffers knew not to write anything even remotely critical about the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the ten-member regional alliance that Burma joined in 1997. “We are encouraged, though, to write anything bad about Thailand,” said the editor, noting that the two countries are currently embroiled in a border dispute. “But that could also change.” In June 2001, a dam broke near Wundwin township, about 100 miles south of the city of Mandalay in central Burma. The barrier had silted over and become unstable due to poor maintenance and unusually heavy rains. When it finally gave way, some 200 villages were flooded. As many as 1,000 people died, some of them bitten by poisonous snakes that had been swept along by the deluge.

In June 2001, a dam broke near Wundwin township, about 100 miles south of the city of Mandalay in central Burma. The barrier had silted over and become unstable due to poor maintenance and unusually heavy rains. When it finally gave way, some 200 villages were flooded. As many as 1,000 people died, some of them bitten by poisonous snakes that had been swept along by the deluge. In March 2000, The Myanmar Times opened for business. The weekly English language paper features snazzy graphics and good paper. It is published by an Australian entrepreneur named Ross Dunkley, who prepared for the job by serving as managing director of the Vietnam Investment Review, one of the first private magazines in that heavily censored country.

In March 2000, The Myanmar Times opened for business. The weekly English language paper features snazzy graphics and good paper. It is published by an Australian entrepreneur named Ross Dunkley, who prepared for the job by serving as managing director of the Vietnam Investment Review, one of the first private magazines in that heavily censored country.