Mission Journal: With a new presidential commission investigating the abduction of Ahmed Rilwan Abdulla and the murder of Yameen Rasheed, CPJ’s Asia program research associate Aliya Iftikhar travels to Malé in late February to speak with the bloggers’ families about their pursuit of justice, and with authorities about the progress and challenges in the cases.

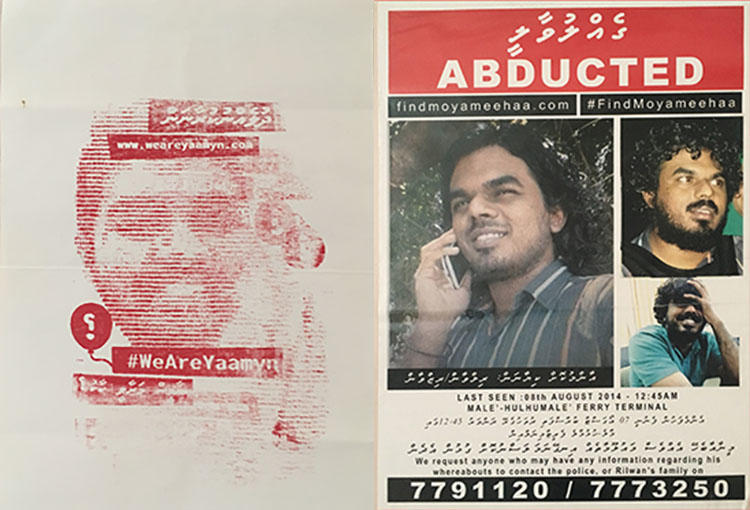

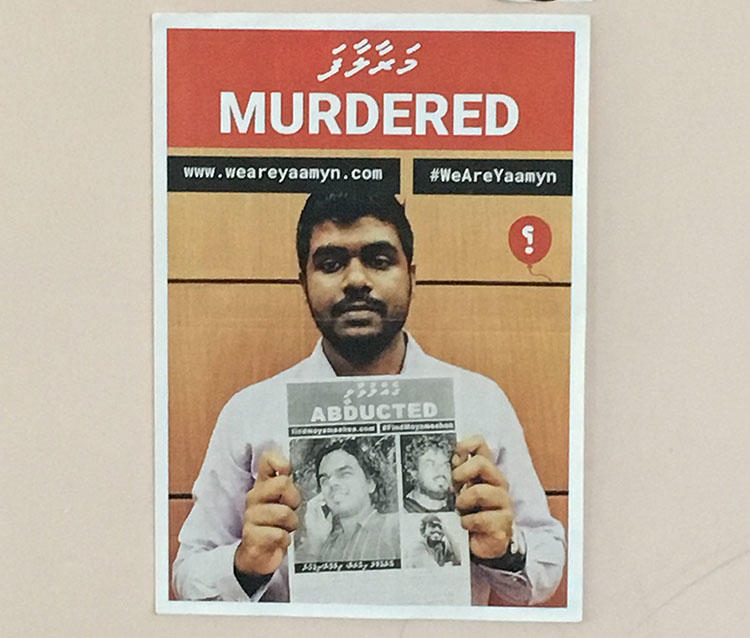

In her pink hijab and floral dress, Fathimath Shehenaz was easy to spot in the small crowd of protesters gathered outside the Malé parliament building, carrying signs emblazoned with #FindMoyameeha and #WeAreYaamyn. Shehenaz has been a mainstay at these protests, as she seeks answers to the abduction of her brother, Ahmed Rilwan, five years ago.

On the afternoon that we met at the protest, parliament had refused–for the fourth time–to vote on a bill to give investigative powers to a newly formed presidential commission on enforced disappearances and murders.

The commission has brought hope that justice will be served in several cases in the Maldives, including those of Rilwan and Yameen Rasheed, a blogger murdered in April 2017. However, without parliamentary approval of the investigative powers, the commission will be unable to work independently of the police and judiciary.

At roughly 2.5 square miles and with a population of about 142,000, Malé is the epicenter of politics, finance, and commerce in a nation comprised of 1,190 small islands and sandbanks. Given its small population, the attacks on Rilwan and Rasheed shook the city, both for their brazenness and violent nature. Through marches, campaigns, and protests, their families have ensured that the journalists’ names were not forgotten, and their cases became political campaign issues. As a presidential candidate, Ibrahim Mohamed Solih met both families last year, and promised to open investigations.

“We fought for this justice, and that is the only reason we’re talking about this, even after five years,” Rilwan’s brother, Moosa, told me. “If we had been silent, there wouldn’t even be a commission to investigate these things.”

At her home in the capital, Rilwan’s mother, Aminath Easa, said she was optimistic about the new commission and could see that it was trying, unlike under the past administration, whose officials never came to meet her and did not conduct a thorough investigation.

“I just want to know what happened, if he’s dead or alive,” Easa said, with tears in her eyes.

The commission was announced on Solih’s first day in office in November. His was a surprise win. His party–the Maldivian Democratic Party–first came to power in 2008 in the country’s first democratically held elections, but a coup in 2012 ousted the elected president. The following year, Abdulla Yameen Abdulla Gayoom came to office, bringing in a period of authoritative rule during which journalists were attacked and defamation cases threatened to send them to jail and their outlets into bankruptcy.

During this period, religiously motivated attacks targeted writers who were popular on social media, including blogger and former editor of Haveeru, Ismail Khilath Rasheed (known as Hilath), who survived an attempt on his life in June 2012; Afrasheem Ali, a former member of parliament, killed in October 2012; Rilwan; and Yameen Rasheed.

The attacks were connected, Husnu Al Suood, former attorney general and president of the commission, told me in his office. What did the four share in common? All spoke about social issues, human rights, and religion. And all were popular, with large followings, typically online. The attacks were masterminded by one group and were motivated by religious, militant elements, with gang involvement, Suood said, without naming the group.

The government was aware of the group as early as 2011, but failed to go after them for political reasons, Suood said, adding that the people were targeted over their writing. Aside from Saudi Arabia, the Maldives is one of the only other countries that bills itself as “100 percent Islamic.” Religion is an extremely sensitive topic, and politicians have historically kowtowed to sheikhs and religious leaders to help their political image.

“There was an identified group and the state knew that … and had they stopped or investigated and prosecuted the people behind Rilwan’s case then Yameen Rasheed’s would not have occurred,” he said. “Even in Hilath’s case, no action was taken at that time.” Suood added, “Had they stopped that in 2012, even Afrasheem’s case I doubt could have happened.”

During our meeting at the president’s office, Ibrahim Hood, the president’s chief communications strategist, said, “One of the reasons these groups thrive is the laissez-faire approach that has been taken with regards to them.” He added, “I think they had state protection. I don’t know whether it was deliberate or some kind of implicit arrangement of ‘these are the boundaries.’ We’ve taken a more no-nonsense approach. It’s no longer a free-for-all.”

Extremists have been more influential and growing in number, Rilwan’s brother, Moosa, said. Politicians use religion as a tool to achieve their agendas and get power, but they’re also afraid of them, he said.

Rilwan was a reporter for Minivan News (now the Maldives Independent), but he was better known for his blog where he was known as “Moyameehaa” or “madman” and wrote about social issues, human rights, and religion. Moosa remembers him as fun-loving, friendly, and kind. Two weeks before his abduction, he published a story about Maldivians leaving to fight for the extremist group Islamic State in Syria.

The state’s negligence in investigating Rilwan’s abduction has been well-documented, with a court last year reprimanding authorities when it acquitted two suspects. The complicity and involvement of authorities have also been established. Police surveilled Rilwan and there was interference in the investigation that followed, Suood said, adding that a suspect managed to flee to Syria, with help from authorities.

The former government has denied involvement. The Foreign Ministry told a U.N. working group on enforced disappearances that authorities rejected the allegations of responsibility or involvement.

In Rilwan’s case, Suood said, the commission has established a motive, something that had previously evaded authorities. He declined to elaborate, saying the information would be released in a report when the commission completes its investigation.

The current acting police commissioner, Mohamed Hameed, told me that police will review and take action against anyone named in that report as being complicit or negligent in the investigation.

One of the most active voices in pursuing justice for Rilwan was Rasheed, whose website, The Daily Panic, providing satirical social and political commentary. He was stabbed to death more than 36 times in the stairwell of his apartment building. Seven suspects were arrested and a trial started 18 months ago. Initially held in secret, the trial has been opened up, but the number of people allowed to attend is limited and no hearing has been held in nearly four months, Rasheed’s sister, Aisha, said.

“Yameen was relentless in pursuing Rilwan’s case, and it is very difficult, even if you look at Yameen’s case, for people to be continuously asking questions, fighting for justice, because everyone has their own life, but Yameen did that,” Aisha Rasheed said.

What is sad, she said, is the narrative created around bloggers–that they are atheist or irreligious– tarnishes their image and is used to justify the attacks.

In Rasheed’s case, authorities were also accused of negligence, though the civil court threw out a case filed by the family in 2017.

Aisha Rasheed, who previously worked in the police forensics department, said she saw discrepancies in the way the investigation was being carried out almost immediately, noting that the crime scene was processed in less than two hours.

“I know the procedures they have to follow. I didn’t feel they were doing that,” she said. “There was massive negligence on the police side, whether they admit it or not.”

By the time she and her family had returned from Rasheed’s funeral, the walls had been painted over, almost like nothing had happened just hours prior.

Suood said there was less indication of state-involvement in Rasheed’s case. But Aisha Rasheed said she finds that hard to believe, especially because authorities were aware of threats on her brother’s life. “I believe this is just the tip of the iceberg and that there is a huge organization behind this that is targeting people, training people, and radicalizing them,” she said. “The people at the top, they enjoy impunity.”

“[Rasheed] was outspoken, he didn’t mince words, he was brave … and he had mass appeal, he could communicate with a lot of people,” she said. “Of course he was afraid of the death threats, but it was more important to him to have a conscience than to bow down.”

“I think they wanted to make an example out of him … People are very afraid, because anything is possible in this country,” she said. “When they couldn’t win at words, they silenced him.”

Rilwan’s abduction also hangs over his former colleagues at the Maldives Independent. “I think we unconsciously dropped certain stories, and we began asking if it was worth it to put reporters at risk,” Ahmed Naish, the acting editor, said

Suood told CPJ that he was confident that the commission will bring the cases to prosecution. He said he believes the investigation already has enough new evidence in Rilwan’s case to appeal the acquittal last year. But, he said, the more time that goes by, the harder it will be for the courts to prosecute the Rasheed case. He added that the lapse in time allows perpetrators and their supporters to try to influence witnesses and judges.

Rilwan’s brother, Moosa, was less optimistic. He said he believes the key is to prosecute those in authority who were complicit and negligent.

The acting police commissioner, Hameed, said, “It’s quite evident that police hadn’t treated Rilwan’s case as a serious case from the start and that it was not carried out in a timely way.”

However, the commission president Suood said that without the investigative powers requested in parliament, its power will be limited.

Suood said he anticipates challenges and pushback, including threats from gangs and people complicit who are still in positions of power. “There will be a lot of challenges in that respect, because this is a small place and one is connected to several others who are influential and who are in power,” Suood said. “It will be difficult if we don’t get that legislation passed.”

[Reporting in Malé]