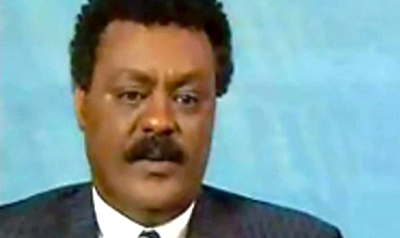

On Wednesday, the Swedish newspaper Expressen published what it described as an exclusive interview with Ali Abdu–Eritrea’s long-time information minister, government spokesman, and censor-in-chief–who vanished from public view in November. The piece confirmed that Ali had gone into exile, but it shed no light on the whereabouts and well-being of more than two dozen imprisoned journalists.

The newspaper actually communicated with Ali’s brother, Saleh Younis, who said he was speaking for the former minister; most journalists said the report appeared to be credible. Ali, 47, was a close confidante of President Isaias Afewerki and for many years managed the country’s tightly controlled system of news and information. The government shut down the country’s private press in a September 2001 crackdown on dissent, and eventually barred all international journalists as well. All news is provided through state media. CPJ considers Eritrea the most censored country in the world.

The Red Sea nation also holds 28 journalists in secret prisons, according to CPJ research. These journalists, some held now for more than a decade, were never charged with crimes or put on trial. As the years have passed, less and less has been known of their fates; unconfirmed reports say several have died. Over the years, Ali repeatedly dismissed or ignored international inquiries about their fates.

The interview specifically addressed the case of Swedish-Eritrean journalist Dawit Isaac, co-founder of Setit, once Eritrea’s largest newspaper. Ali, incredibly, claimed that neither he nor other members of the government have any knowledge of the fates of the jailed journalists, Saleh recounted for the paper.

In a subsequent column on his news site Gedab News, Saleh also sought to absolve his brother of responsibility. “If the entire journalistic staff of Expressen was to interview [Eritrean government cabinet ministers] for days, weeks, months; if they were to water-board them, they would not be able to get a single useful information on the whereabouts of Dawit Isaac or any of the thousands of Eritreans who have been made to disappear,” he wrote. Saleh asserted that the Eritrean government operated on oral orders without any paper trail; security forces carrying out arrests had no knowledge of who they were picking up; and guards had no idea how long inmates would be in custody.

Yet in November 2005, after Dawit Isaac was briefly set free from years of secret detention without trial, Ali told Agence France-Presse that the journalist would be returned to prison, describing the release as a temporary leave for medical tests. In 2007, Ali confirmed to CPJ reports that one of his employees, TV presenter Paulos Kidane, had died while attempting to escape the country. Ali declined to say how Paulos died, leaving unaddressed wide speculation that the journalist was shot by Eritrean border guards.

Former state news media employees, who form one of the largest diasporas of exiled journalists in the world, do not believe the former minister. “I am sure he has detailed information; he knows who is dead and who is alive, but he is trying to set himself free by shouldering the blame to the president,” Aaron Berhane, once the editor-in-chief of Setit, told CPJ. “Ali knows very well the whereabouts of Dawit Isaac and the rest of the journalists.”

Esayas Isaac, who has launched a tireless campaign to free his brother Dawit, is understandably frustrated. “After 11 years waiting for answers, you feel angry, you feel frustration,” he said. Ali’s obfuscation may be due to the fact that his own family is now in prison. After he left the country, Eritrean authorities arrested his father, teenage daughter, and brother, according to news reports.

The imprisonment of family members has meant that Ali Abdu shares the same sort of anguish that Esayas Isaac has long endured. “I actually hope Ali Abdu now understands the situation better since he has members of his own family in prison,” Esayas said. Esayas says that despite his anger, he is willing to build a relationship with Ali if the former minister agrees to help him find his brother.