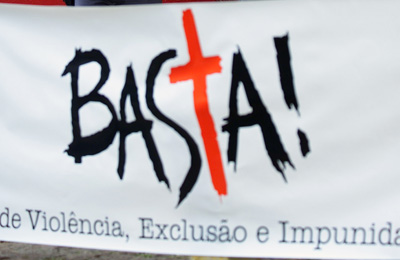

Brazil, Pakistan, and India–three nations with high numbers of unsolved journalist murders–failed an important test last month in fighting the scourge of impunity. Delegates from the three countries took the lead in raising objections to a U.N. plan that would strengthen international efforts to combat deadly anti-press violence.

• CPJ’s 2012

Impunity Index

Meeting in Paris, delegates of UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Council of the International Programme for Development of Communication were expected to endorse the U.N. Inter-Agency Plan of Action for the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity. But a debate that was scheduled for two hours raged for nearly two days, ending without the 39-state council’s endorsement.

The plan, which had been in the works for more than a year, is still proceeding through other U.N. channels, although implementation and funding could face continued difficulties if these nations persist in raising objections. Perhaps more important: Brazil, Pakistan, and India–each ranked among the world’s worst on the Committee to Protect Journalists’ 2012 Impunity Index–missed an opportunity to send a strong message that they do not condone anti-press violence.

Among its many security-related measures, the plan would strengthen the office of the U.N. special rapporteur for free expression, assist member states in developing national laws to prosecute the killers of journalists, and establish a U.N. inter-agency mechanism to evaluate journalist safety. “The U.N. plan is a unique road map, designed by U.N. agencies, programs, and funds, as well as professional associations, NGOs, and member states to address the issue of the safety of journalists,” said Sylvie Coudray, the UNESCO senior program specialist who has managed the plan’s development. CPJ participated in UNESCO’s consultative process.

During the two-day UNESCO debate, representatives from India and Pakistan repeatedly questioned whether the initiative was appropriate under UNESCO’s mandate. They also dominated the session with calls for greater “transparency” in UNESCO’s sources for information on anti-press attacks. Brazil raised procedural objections, asserting that UNESCO did not have authority to enact the plan.

Delegates from the United Kingdom, the United States, the Netherlands, Niger, Albania, and other countries countered that the plan is imperative in light of the growing number of victims of anti-press violence. “Not endorsing this plan,” the Albanian delegate said, “would send the wrong message to the world and to the perpetrators.”

In the end, the council adopted a compromise resolution that allows the plan to move ahead through the U.N. Chief Executives Board, which centralizes operations of specialized U.N. bodies. But UNESCO will have to present another work plan at its executive meeting in spring 2013.

“The failure of the council to formally endorse the action plan, as it was invited to do, is a setback and gives its opponents a chance to renew their hostile attack on the plan and to delay it as it moves on through the other hurdles it must overcome in the U.N. system to get approval and become reality,” said William Horsley, the international director of the Centre for Freedom of the Media at the University of Sheffield, who has been closely monitoring the plan.

In written responses to CPJ queries, a senior Pakistani official said that while his country “welcomes attempts at the international level to find a workable solution,” the U.N. plan “has to be tackled in a comprehensive manner with the cooperation of maximum number of member states at appropriate for[ums].” While acknowledging that Pakistani journalists had been killed, the official said it would be “unfair to say outrightly that Pakistan has a high rate of unresolved cases.” He questioned whether journalist deaths were work-related, and attributed Pakistan’s fatality rate to his country’s war on terror.

Pressure within nations may be a key to keeping the plan on track. In Pakistan, CPJ International Press Freedom Awardee Umar Cheema took his government to task, while Brazilian news media put their government on the defensive with extensive coverage of the story. In an interview last week with CPJ, a senior Brazilian official framed his delegation’s objections as procedural, and said the country would not stand in the way of the plan’s further progress. “We are 95 percent in favor of all the articles here, but some of them we think should follow a different procedure,” the official said. “We are very committed to protecting journalists, although we recognize we have many problems that need to be addressed.”

Despite some dissenting nations’ calls for “transparency” in UNESCO’s information sources, the statistics themselves are clear. More than 560 journalists have been murdered with impunity worldwide over the past two decades, CPJ research shows. Already this year, eight journalists have been murdered across the globe. Pakistan, Brazil, and India all have among the highest rates of unsolved journalist murders per capita in the world, CPJ’s new Impunity Index shows.

States shouldn’t delay this plan. The killers of journalists are acting now.