For Geneviève Zongo, every December 13 revives excruciating memories of the loss of her husband Norbert Zongo, editor of the weekly L’Indépendant. He was assassinated in 1998 while investigating the murder of a driver working at Burkina Faso’s presidential palace. More painful still is that the killers who ambushed Zongo’s car, riddling it with bullets and torching it, have never been brought to justice.

Early on this anniversary morning, as has become her ritual, Geneviève Zongo attended a prayer service at her local church in the capital, Ouagadougou, and headed home, she told me. She said she no longer visits Gounghin Cemetery, where her husband’s remains are buried. She sends her two sons, Benjamin, 13, and Constant, 20, to pay respects. “Constant never knew his father. He was barely a year old when [Norbert] was killed,” she told me. Buried in the same cemetery are the Zongo’s brother and two companions, passengers in journalist’s car on that tragic December 1998 night.

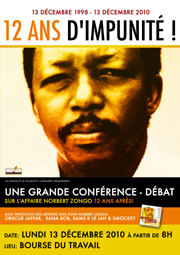

To revive the fading memories of Zongo and renew the struggle against impunity, friends, companions, colleagues, and supporters commemorated the day with a series of public events across the city. After a wreath-laying ceremony at the cemetery, participants gathered in front of the city’s trade union center for a public forum discussing the unsolved case, Abdoulaye Diallo, head of the Norbert Zongo National Press Center told me.

Zongo was killed while he was reporting on the torture and murder of David Ouédraogo, a driver assigned to François Compaoré, the president’s brother and a top aide. “With all the public, we have this thirst for justice, for truth which has not yet been established,” President Blaise Compaoré declared in a December 2008 interview with the daily Sidwaya. But he added: “We have had the impression that a lot of politicization has been made on issues that should really pertain to the judicial system.”

In fact, efforts to purse a thorough, transparent investigation have been frustrated by political pressure from Compaoré’s government–including the harassment of journalists and activists who have called for justice, according to CPJ research. Shortly after Zongo’s murder, a “commission of inquiry” named six officers of the Presidential Guard Regiment as prime suspects. But the examining magistrate in charge of the case, Wenceslas Ilboudo, indicted only one person and then dropped the case entirely in 2006.

The only man indicted was Marcel Kafando, who was convicted in the killing of driver Ouédraogo. Kafando died in 2009, as have two other suspects, according to Diallo. Abdoulaye Barry, the state prosecutor at the time, said the Zongo case would not be reopened until “new developments useful to the manifestation of truth” turned up, according to news reports. Barry was named a presidential adviser in July 2009.

On Monday, local musicians, including Obscur Jaffar, Sana Bob, Sams’K le Jah, and Smockey, had the last words with a rendition of their 2008 tribute song “Artistes Unis pour Norbert Zongo.” Le Jah, whose real name is Karim Sama, has received numerous death threats referencing the Zongo murder for his advocacy. Nevertheless, he told CPJ the artists were planning a series of awareness-raising forum in 2011 to raise awareness of youth about the case.