When Hugo Bustíos Saavedra was killed in 1988, Peru’s government was embroiled in conflict with leftist guerilla groups, many civil liberties had been suspended, and efforts to seek justice in the journalist’s death seemed futile. CPJ and other press freedom groups unsuccessfully tried for years to pressure Peru’s government to investigate Bustíos’ murder, including by asking the Inter-American Human Rights Commission to censure the Peruvian government. Then came several breakthroughs. In 2002, Peru’s Supreme Court effectively struck down an amnesty law that protected soldiers from prosecution for human rights abuses committed during the war. In 2007, two officers were convicted in connection to the Bustíos killing. They, in turn, implicated former army general Daniel Urresti Elera who in April was convicted and sentenced to 12 years in prison for taking part in the killing.

The Bustíos case shows that persistence can pay off. “The sentencing of Daniel Urresti for the murder of journalist Hugo Bustíos is an important step toward ending impunity for crimes against the press in Peru, and a powerful reminder of the long and painful road for families seeking justice,” said CPJ’s Carlos Martínez de la Serna.

Below is a timeline of the key moments in the decades-long fight for justice for Bustíos:

February 20, 1950

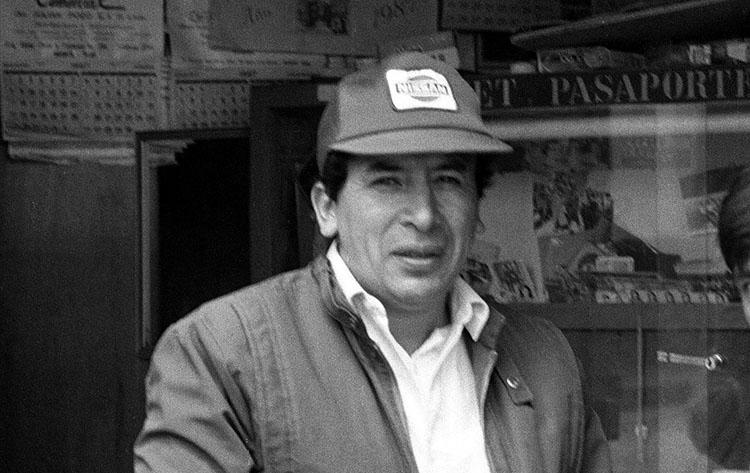

Hugo Bustíos Saavedra is born in the Andean Mountain town of Huanta.

May 17, 1980

Conflict breaks out in Peru after the Shining Path revolutionary group commits the first attack in its “people’s war” against Peruvian government troops. The war lasts two decades and kills or disappears 70,000 people, mostly civilians.

March 1, 1984

The army captures, interrogates, and tortures Bustíos, who is held for 11 days at the Huanta soccer stadium on suspicion of being a Shining Path collaborator. After his release, Bustíos begins working for the Lima newsmagazine Caretas, often writing about human rights abuses committed by both sides in the war.

November 24, 1988

Bustíos is killed in an ambush while reporting for Caretas on the outskirts of Huanta, where Daniel Urresti Elera was the army’s intelligence chief. Witnesses and another reporter wounded in the attack say Bustíos was deliberately targeted by an army patrol. Bustíos was 38.

.

May 10, 1990

CPJ and other watchdogs file a complaint with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, asking it to censure the Peruvian government for violating Bustíos’ human rights and to protect the witnesses in the case. Along with CPJ are Human Rights Watch and the Center for Justice and International Law.

1991

A military tribunal absolves two suspects: Huanta army base commander Victor La Vera Hernández and officer Amador Vidal Sanbento, one of the alleged gunmen in the Bustíos killing.

June 14, 1995

Peru’s congress passes an amnesty law protecting military officers from prosecution for human rights abuses committed during the war against Shining Path rebels.

October 16, 1997

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights finds Peru responsible for Bustíos’ murder and calls for it to carry out a new and impartial investigation into the facts of the case.

Global Impunity Index 2023 Table of contents

2002

Peru’s Supreme Court effectively strikes down the 1995 amnesty law protecting military officers. Judges reopen about 200 of Peru’s most notorious human rights cases, including Bustíos.’

October 2, 2007

A Peruvian criminal court convicts La Vera and Amador. La Vera is found guilty of plotting to kill Bustíos and Amador of taking part in the murder. The court also orders government investigators to determine if others were involved in the murder.

2011

Urresti retires from the army with the rank of general and is put in charge of a Peruvian government unit combatting illegal gold mining. La Vera is released from prison and implicates Urresti in the Bustíos murder.

2014-2015

Urresti serves as Peru’s Interior Minister.

February 27, 2015

Urresti is charged with the murder of Bustíos. CPJ later that year publishes a special report on the Bustíos case as Urresti considers running for president of Peru.

October 4, 2018

A Peruvian court clears Urresti in the Bustíos case.

April 12, 2019

Peru’s Supreme Court overturns Urresti’s 2018 exoneration and orders a new trial.

October 2, 2022

Urresti runs for mayor of Lima, losing the race by less than 1% of the vote.

April 13, 2023

A Peruvian criminal court convicts Urresti nearly 35 years after Bustíos was killed and sentences him to 12 years in prison for taking part in the ambush that killed the journalist. “Justice has been done,” Sharmelí Bustíos Patiño, the journalist’s daughter, said on X (formerly Twitter) on the day Urresti was sentenced. “The road has been hard and painful. Today all that remains is to give thanks.”