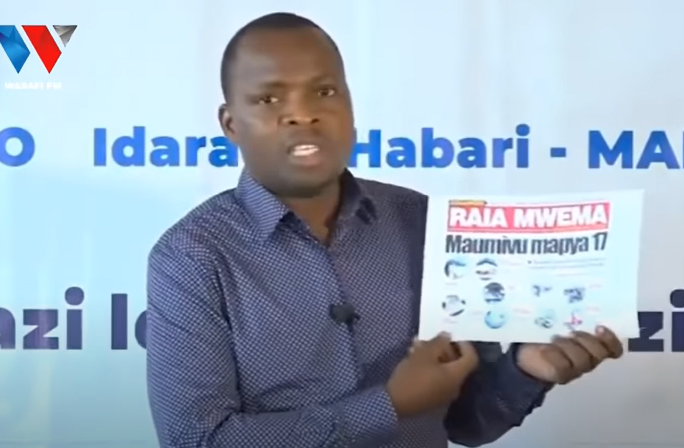

Nairobi, September 15, 2021 — Tanzanian authorities should immediately rescind the suspension of the Raia Mwema newspaper and cease banning media outlets, the Committee to Protect Journalists said today.

In a statement released on September 5, Tanzanian government spokesperson Gerson Msigwa announced a month-long suspension of the privately owned newspaper, beginning the following day. In that statement, he accused Raia Mwema of repeatedly breaking the law and violating professional journalism standards through misleading reporting and incitement.

Raia Mwema editor Joseph Kulangwa denied those allegations but said the newspaper would comply with the order and not file an appeal, according to a letter from the newspaper to Msigwa, which CPJ reviewed, and interviews Kalangwagave with local outlet The Chanzo and German broadcaster Deutsche Welle.

President Samia Suluhu Hassan, who took office in March, previously ordered the reversals of some media bans, and officials in her government have made statements committing to improve conditions for journalists, according to multiple news reports and CPJ reporting.

However, last month her government also suspended Uhuru, a newspaper owned by the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi party, for two weeks, as CPJ documented at the time.

“Promises by Tanzania’s government to improve the country’s press freedom climate will continue to ring hollow if authorities keep up the trend of taking newspapers off the streets on the flimsiest pretexts,” said CPJ Sub-Saharan Africa Representative Muthoki Mumo. “Tanzanian officials should drop their suspension of Raia Mwema and ensure that all newspapers can report the news without fear of suspensions and bans.”

Msigwa, a presidential appointee who is also in charge of Tanzania’s Information Services Department, which licenses newspapers, said in his statement that Raia Mwema broke the law in three separate reports.

He cited an August 21 article about proposed government fees for public locations playing music, saying it “creates panic among the community.” Speaking to Deutsche Welle, Kalangwa said that the report was not published with malicious intent but was meant to tell the public to prepare for the new fees.

Msigwa alleged that a September 3 article about the August 25 shooting of police officers by a person whom Raia Mwema linked to the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi party did not provide adequate evidence that the shooter was a member of that party and could incite hatred within it. He also alleged that the newspaper showed a lack of professionalism by mislabeling the date of that article.

In the letter from Raia Mwema and in Kalangwa’s interviews, the newspaper and editor said that the article only claimed that the shooter was a supporter of the party, not that he was a member, and said that they had visual evidence and witness statements to support that claim. Raia Mwema also asked why the party itself did not file a complaint. In the September 3 article, which CPJ reviewed, a man identified as the shooter is seen wearing a shirt with the party’s colors.

Msigwa also cited another September 3 article about a lawsuit against a former government official, saying that the newspaper failed to make clear in its headline that the official was no longer in office. In that article, which CPJ reviewed, the official is identified as having left office in the first paragraph.

In his statement, Msigwa accused Raia Mwema of breaching sections of the Media Services Act, a 2016 law which imposes prison terms of up to five years and fines of up to 20 million Tanzanian shillings (US$8,600) on those convicted of publishing false news; up to five years in prison and fines of up to 10 million shillings (US$4,300) for first-time offenders convicted of publishing and distributing seditious content; and prison terms of up to six years and fines of 20 million shillings (US$8,600) for publishing false information likely to cause alarm or disturb the peace.

In 2019, the East African Court of Justice ruled that the Media Services Act, which was also cited in the Uhuru case in August, was inimical to press freedom, as CPJ documented. However, Tanzania has not implemented the court’s directive to amend the law, according to multiple reports.

The law was also cited as justification for the closure of several publications under the previous government of President John Magufuli, including in 2017 when Raia Mwema was closed for 90 days, according to reports and CPJ research.

On September 6, CPJ emailed the Information Services Department for comment, but did not receive any reply.

On September 12, Samia moved that department from the Ministry of information, Culture, Arts, and Sports to the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, headed by a newly appointed minister, according to a statement shared by Msigwa and media reports.

After that reorganization, CPJ emailed the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology for comment on September 14, but did not receive any response, and the phone number listed on the ministry’s website did not connect.

CPJ repeatedly called Msigwa for comment and also contacted him via messaging app and Twitter, but did not receive any responses.