A journalist in China uploaded a video to YouTube criticizing the Chinese government’s response to the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan. Another, in Vietnam, left a state-owned newspaper but continued posting stories they wouldn’t let her cover on Facebook. In Egypt, a freelance photographer streamed an anti-government protest from his balcony on Facebook Live. In Iran, two journalists operated a Telegram channel for months after their news website was shut down.

Besides their reliance on social media, these five people have one other thing in common: On December 1, they were all behind bars, according to CPJ’s 2020 annual census of journalists imprisoned for their work. Three were awaiting trial: Zhang Zhan, in China, for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” by fabricating false information (up to 5 years in prison); Tran Thi Tuyet Dieu, the former professional in Vietnam, for conducting anti-state propaganda (up to 20 years in prison); and Egyptian photographer Sayed Abd Ellah, for spreading false news and membership of a terrorist group, among other charges. In Iran, Roohollah Zam and Arash Shoa-Shargh were sentenced to death in connection with their work for the Iranian Amad News website and Telegram channel; Shoa-Shargh’s sentence was commuted to 10 years; Zam’s was upheld. On December 12, state-linked Iranian media reported that he had been executed by hanging, an injustice CPJ condemned in the strongest possible terms.

Gone are the days when CPJ would fax authorities to urge a journalist’s release from prison; now we frequently utilize Twitter or WhatsApp to engage recalcitrant officials. Social media platforms provide a direct line for both reporting and advocacy. In Egypt, Abd Ellah’s wife documented his arrest on YouTube, and much of what we know about his case is thanks to Facebook posts from press freedom advocate Khaled el-Balshy.

But social media also complicates CPJ research, most notably when journalists’ posts and accounts go missing from global platforms. Despite incremental progress toward transparency, social media is still a black box for press freedom research. It’s often not clear when or how content was removed, even when it forms the basis of an unjust criminal prosecution, like the ones on CPJ’s list.

The need for more complete, granular transparency is becoming more urgent. Justifiable pressure to remove “terrorist” or criminal content from the internet is propelling efforts to streamline regulation across platforms or jurisdictions, as CPJ has noted. Those efforts are welcome, as long as it’s clear how they will distinguish terrorists and criminals from journalists who are accused and convicted in reprisal for reporting. Transparency is a first step to revealing how individuals and institutions answer the difficult questions that are all too familiar to CPJ staff: Was this punishment for reporting, and how do we know?

The journalists described above are not unique. At least three other imprisonments in Vietnam are linked to Facebook posts; Zam and Shoa-Shargh were two of six cases in Iran involving Telegram channels. Nor are their countries outliers: Social media activity was cited as evidence in at least 7 out of 37 cases in Turkey.

Social media posts often attract scrutiny from prosecutors because global platforms provide an essential alternative source of information. In Azerbaijan, for example, the independent news website Azel.tv was offline when CPJ reviewed it after the arrest of its editor, Afgan Sadygov, on retaliatory extortion charges in May 2020. But the site’s YouTube channel remained operational when we were researching the census, providing CPJ with a record of that work which might otherwise have been lost.

When social media activity is the basis of a criminal charge, CPJ assesses it for journalistic intent, even without professional accreditation. Social media provides a platform for many who would be excluded from the profession, especially in countries where independent media is repressed; the Vietnamese Ministry of Information and Communications revoked Tran Thi Tuyet Dieu’s official press card in 2017.

Making these calls relies on our close review of the content. Yet often, by the time we become aware of it, it’s not there. Posts may be deleted or set to private—voluntarily or under duress—as prosecution looms. But in published transparency reports, many social media companies also acknowledge removing information and accounts following notification either from a court or official flagging legal violations, or from an individual complaining under terms of service.

Journalists who are deemed to have violated local law are likely subjects of such notifications, but when content is missing, the rationale and the remedy are rarely clear to third parties. Some items hidden following legal demands are labeled in the country and remain visible overseas, as CPJ has explored with journalistic Twitter posts in Turkey and India. But Tran Thi Tuyet Dieu is accused on the basis of a YouTube account that hosted no content as of December 2020, and two Facebook accounts. One of those, still extant, was apparently created when her main account was unavailable to her in 2018, allegedly because local police had it briefly shut down; it was shuttered again at the time of CPJ’s 2020 review.A report published on November 30 by Amnesty International documented “increasing censorship of political expression” on Facebook and Google, which owns YouTube, in Vietnam as a result both of official orders and of unofficial groups who report journalists and activists to the companies for suspension.CPJ requested comment via email from Facebook and Google, but received no response before publication.

Telegram separately removed the Amad News channel in 2017 after the Iranian telecommunications minister tweeted allegations that it was inciting violence; Pavel Durov, Telegram CEO and founder, said they had instructed followers to “use Molotov cocktails against police,” Vox reported at the time. Telegram was itself banned for less than a year later for reasons that included allowing some of its estimated 40 million Iranian users to spread anti-government propaganda and protests, according to the BBC. The Amad News journalists continued their work in a different Telegram channel that was not shuttered, CPJ research found, spreading embarrassing information about Iranian officials and the timings and locations of protests in 2017. Iran executed Roohollah Zam for crimes including spreading false news, working with foreign intelligence agencies, making money illegitimately, and insulting the supreme leader.

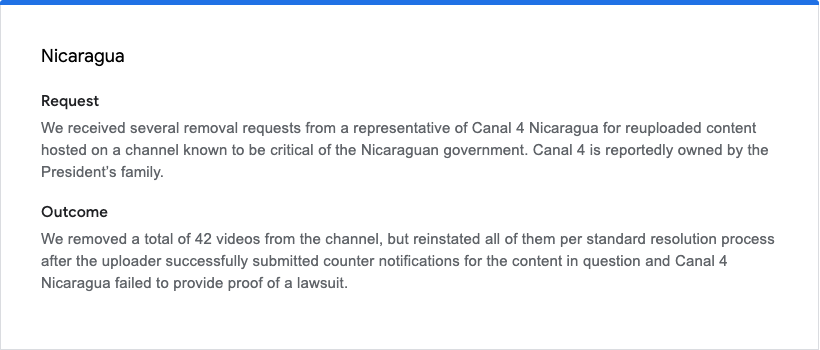

Transparency reporting, as CPJ has long acknowledged, is the first step for social media companies to reveal how they make decisions about content and data. Google’s transparency report, for example, offers generic examples that showcase the company’s periodic refusal to comply with attempts to restrict journalism on services like YouTube. That’s welcome, but not enough. Take one recent example from Nicaragua:

This is the extent of Google’s disclosure, and it recalls a case involving Nicaraguan journalists Miguel Mora and Lucía Pineda Ubau, who were jailed for several months during a crackdown on independent media in 2018. Mora and Pineda—who were among CPJ’s 2019 International Press Freedom Awardees—contacted CPJ after failing to get YouTube to restore news channels that were shut down in March; access to their video archive was not restored until after CPJ documented the incident in May.

Is it the same case? Google did not respond to an email request to check, and there’s not enough detail to know for sure—and no guarantee that more detail would serve the journalists involved, rather than raising privacy concerns. But if it is the same, there’s a couple of things worth pointing out: first, that the “standard resolution process” was not as straightforward as that language implies, and second, that the disclosure draws on CPJ’s knowledge of that incident, instead of adding to it.

What we need from transparency reporting are the things we don’t already know. How do companies assess whether content that is flagged for sanctions is journalistic? How frequently does it happen, and with what success rate?

If companies don’t challenge the systems that put journalists behind bars, they risk aiding in the suppression of news that repressive governments don’t want the world to hear. This is most obvious in China, where citizen journalist Zhang Zhan turned to Twitter and YouTube to share information about the coronavirus outbreak. Accounts of her work don’t say why she resorted to foreign platforms, which are blocked locally, and only accessible by VPN. But one clue lies in the fact that grassroots reporting is heavily censored on domestic social media, as researchers documented in March—even regarding the imminent public health crisis that became a global pandemic. Zhang was arrested in May, and is one of 47 journalists CPJ documented behind bars in China in the 2020 census. In December, the Chinese human rights news website Weiquanwang published information from her lawyer saying she was under 24-hour restraint to administer a feeding tube after she went on hunger strike to protest her innocence; she told her lawyer she had not fabricated information, only interviewed the citizens of Wuhan.