We have the laws and institutions to fight attempts at information control

By David Kaye

Yevgeny Zamyatin’s strikingly original 1920s Russian novel We gets read far less than its canonical English-language descendants, Brave New World and 1984. Yet George Orwell knew of and clearly drew from Zamyatin’s book in creating 1984. The homage-paying is obvious: A solitary hero struggles to define himself in relation to society; a state and its mysteriously cultish leader control privacy, information, and thought; love is prohibited and freedom is categorically rejected; the violence and brutality of power lurk beneath a seemingly clean and mechanized society; common words are redefined and propaganda is pervasive in daily life; and, in total, reality is rejected in favor of myths and lies.

On the first page of We, which is set hundreds of years into a dystopic future, the hero, known as D-503, records in his notebook a proclamation found in the One State Gazette about the building of a great spaceship. The proclamation announces that the ship soon “will soar into cosmic space” in order to “subjugate the unknown beings on other planets, who may still be living in the primitive conditions of freedom, to the beneficent yoke of reason.” The proclamation goes on, “If they fail to understand that we bring them mathematically infallible happiness, it will be our duty to compel them to be happy.”

“But before resorting to arms,” the proclamation magnanimously adds, “we shall try the power of words.”

D-503 gradually recognizes that reality varies from the word of the governing One State, whose plans for extra-planetary subjugation reflect what it has already accomplished on Earth. He comes to resist the theology behind the One State rejection of freedom, and the novel extrapolates from what was, for Zamyatin, the contemporary abuses of early Bolshevism to draw a direct connection between information control and the elimination of privacy and the fundamentals of political liberty.

Though the book was written almost a century ago and is set centuries into the future, its core conflict seems particularly timely: 2016 gave us repeated opportunities to reflect on the core ideas of freedom rejected by any number of states. That is not to say that any one government’s behavior in 2016 mirrored the single-minded totalitarianism of the One State, but the novel’s themes could not be more relevant to our current situation, in which governments and non-state actors repeatedly throttle, suspend or entirely cut off the flow of information, redefine language to the detriment of reportorial fact-finding and attack those responsible for keeping us educated and able to engage in discourse about matters of great public interest.

As this edition of Attacks on the Press demonstrates, governments worldwide are threatening the flow of information, whether through online restrictions, physical attacks and harassment, the abuse of legal processes or the enactment of overly broad rules of law. Those actions rest on the same premises of power and insecurity that dominated the One State: If the people are given the tools to figure out the truth (or a truth) for themselves, governmental power will weaken. The more corrupt and greedy the pursuit of power, the greater the incentive for people in authority to limit public debate and access to information.

Few doubt that such authoritarian tendencies are on the rise, resulting in direct attacks on the practice of journalism. But unlike in Zamyatin’s world, we have a network of international legal protections guaranteeing the rights to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers and through any media, including Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. States have the authority to restrict such rights only when the changes are rooted in law and when they are considered necessary and proportionate to achieve a legitimate objective. However, within this framework of law and the institutions designed to protect it, dozens of categories give cause for alarm or even panic (which is how my October 2016 report to the U.N. General Assembly was received).

The following are the five most notable categories that are having a direct impact on journalism and journalists:

Traditional censorship

Traditional censorship is alive and well around the world. Some governments promote theories of why their citizens cannot access information, such as public order or morals, resulting in such infamous tools as the Great Fire Wall in China, designed to limit online information for Chinese citizens. Other governments are disrupting internet and telecommunications services, often without any explanation, usually during public protests or elections, shutting down entire networks, blocking or throttling the speeds of websites and platforms, and suspending telecommunications and mobile service. Access Now documented more than 50 shutdowns in 2016, though I suspect the number is even higher.

Outside of digital space, other governments require that specific myths be told and retold in the media and educational textbooks. Some states’ laws enforce official narratives by criminalizing breaches of public solidarity, or “misinformation” or “false news.” While the problem is undoubtedly exacerbated by the failures of internet search engines and social media to deal with those gaming their systems, I am afraid that the age-old problems of propaganda and what many in the United States call “fake news” could result in just the kind of restrictions that oppress individuals in authoritarian regimes.

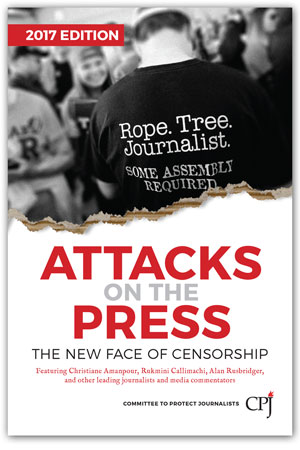

There are also softer forms of censorship in democratic societies involving pressure to adhere to government narratives. Donald Trump’s attacks on journalists are notable in this regard, and are serious causes for alarm. In Japan, I found that a variety of factors – government pressure, media concentration, a tradition of access journalism and a lack of journalistic solidarity – combine to establish norms of censorship and self-censorship.

Terrorism

One of the gravest threats to expression today is rooted in the reality of terrorism and threats to national security. Nobody should doubt that states have an obligation to protect life against groups such as the Islamic State and other terrorist organizations. Yet states often use the grounds of anti-terrorism, counter-extremism, and national security as broad bases to limit the flow of information. Turkey has become a leading practitioner of such an approach to attacks on the media. Of course, genuine incitement, demonstrated terrorist recruitment, and suppression of legitimate secrets can all be handled through mechanisms of law, including criminal law. But we see much more than that. The reliance on counter-terrorism serves as a catchall to throttle or shut down the media and justify the detention of journalists, bloggers, and others. My colleagues in the European, inter-American and African systems and I addressed this issue in our annual joint declaration of 2016 because it is one of the predominant themes of restriction globally. In the text of that declaration, we expressed alarm over what we described as:

…the proliferation in national legal systems of broad and unclear offences that criminalise expression by reference to [countering and preventing violent extremism], including offences “against social cohesion”, “justification of extremism”, “agitation of social enmity”, “propaganda of religious superiority”, “accusations of extremism against public officials”, “provision of information services to extremists”, “hooliganism”, “material support for terrorism”, “glorification of terrorism” and “apology for terrorism”.

We also emphasized the importance of adherence to human rights law:

States should not restrict reporting on acts, threats or promotion of terrorism and other violent activities unless the reporting itself is intended to incite imminent violence, it is likely to incite such violence and there is a direct and immediate connection between the reporting and the likelihood or occurrence of such violence. States should also, in this context, respect the right of journalists not to reveal the identity of their confidential sources of information and to operate as independent observers rather than witnesses. Criticism of political, ideological or religious associations, or of ethnic or religious traditions and practices, should not be restricted unless it involves advocacy of hatred that constitutes incitement to hostility, violence and/or discrimination.

Legal restrictions

States are adopting legal proscriptions designed to do away with criticism. Some states punish “propaganda against the state” or “insult” to the states’ leadership. Others penalize sedition, targeting those who criticize the state or its leaders, such as the Malaysian cartoonist Zunar, who faces the possibility of dozens of years in prison, and who is currently subject to a travel ban as a result of his cartoons attacking Prime Minister Najib Razak. Often, critics are punished on grounds of disrupting public order or on the basis of so-called lèse-majesté laws or criminal or civil defamation lawsuits.

Governments are increasingly pressuring internet platforms to take down critical content, among other things. Twitter, like other major internet platforms, publishes a regular transparency report that underscores the extent to which states are seeking takedowns. Some material may be taken down legitimately on grounds of incitement to violence or genuinely actionable defamation. Such takedowns should always require the intercession of judicial authorities, but often they are not.

Surveillance

In We, the “numbers” (i.e., citizens) live in glass apartments and are given one hour a day to draw the curtains for personal time. Today, we see a marked increase in surveillance that is not based on reasonable suspicions of criminal activity nor authorized by the rule of law. We see at least two other forms of surveillance that undermine the confidence we can have in our communications, our browsing history online, our associations, our sources and research, and so forth.

In 2013, Edward Snowden famously disclosed the abuses of mass surveillance conducted by the United States and the United Kingdom. In the past year, France, the U.K., and even Germany–an erstwhile champion of policies strictly limiting the state’s snooping powers–have considered or adopted new, intrusive measures of surveillance. In the case of Germany, legislation failed to provide protections for journalists. The U.S. government has been advancing problematic forms of social media monitoring at the border, with serious potential consequences for foreign journalists.

But they are not alone. Russia’s Yarovaya Law, China’s Cybersecurity Law and Pakistan’s Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, all adopted this year, impose surveillance of communications trafficking their platforms. In the context of such measures, states are also cracking down on the tools that can provide individuals with a modicum of privacy, such as encryption and anonymity designed to protect journalists, activists, minorities, dissenters, and others. Increasingly, states seek to limit the availability of such tools precisely because they interfere with surveillance.

Meanwhile, states that might not have such technical advantages have been able to purchase software on the open market to conduct targeted surveillance of activists, journalists, and ordinary citizens. For one example, I filed an amicus brief supporting the position of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which is currently suing the government of Ethiopia on behalf of an Ethiopian-American activist whose computer in the U.S. state of Maryland was infected with malware and surveilled for nearly six months by Addis Ababa.

Digital distortion

From a normative perspective, we remain at an early stage of thinking about human rights in the digital age, but even so, private actors own and control what many of us think of as public spaces. They have hundreds of millions of individual users–or in Google’s and Facebook’s case, billions. They are proud of that, as they should be. They run businesses and make a lot of money and create a lot of jobs.

They also manage expression–they take down content, mediate what’s permissible, decide the information that we might see. It’s all quite opaque, hidden by proprietary algorithms and uncertain human input. Meanwhile, they have terms of service that are usually not drafted in order to advance human rights norms. Perhaps that is acceptable, because of course they are private enterprises. But when information and access require membership in these social media giants, to what extent can they hide behind the wall of private enterprise? To what extent does the private sector owe a responsibility to ensure access not merely to information but to fair, non-distorting information? Is law an approach that does more good than harm? I think there is reason for concern and monitoring, because what we increasingly see are walled gardens, where individuals get only the information the platform permits.

As noted, we are seeing various echoes from the politically minded dystopic novels of the past in the rejection of the depicting or arguing about reality. And it will get worse unless we name the problem, organize to resist it, and ultimately use the tools provided by human rights laws at national, regional, and international levels to address it.

In We, Zamyatin chuckles at “one of the absurd prejudices of the ancients – their notion of ‘rights.'” Here is what he says, and it’s both a clear-eyed view of the rhetoric of the powerful and the necessity of resisting it:

…suppose a drop of acid is applied to the idea of ‘rights.’ Even among the ancients, the most mature among them knew that the source of right is might, that right is a function of power. And so, we have the scales: on one side, a gram, on the other a ton; on one side ‘I,’ on the other ‘We,’ the One State. Is it not clear, then, that to assume that the ‘I’ can have some ‘rights’ in relation to the State is exactly like assuming that a gram can balance the scale against the ton? Hence, the division: rights to the ton, duties to the gram. And the natural path from nonentity to greatness is to forget that you are a gram and feel yourself instead a millionth of a ton.

The year 2016 should provide us with a renewed opportunity to remind ourselves that we yet have the tools to assert ourselves not as grams to be weighed against the tonnage of the state. We need to protect and reform the institutions we have, to ensure that they work to protect rights, that we move to a place where we can celebrate and criticize the world as it is, or we think it is, not as our leaders want us to perceive it to be. That’s what the practice of journalism is all about.

David Kaye is the U.N. special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression. He is clinical professor of law at the University of California, Irvine, School of Law, where he teaches international human rights and humanitarian law and directs a clinic in international justice.