As a new presidential administration prepares to take over the U.S., CPJ examines the status of press freedom, including the challenges journalists face from surveillance, harassment, limited transparency, the questioning of libel laws, and other factors.

President Obama has announced that the 6,700-page Senate Intelligence Committee report on the CIA’s use of torture will remain classified. It will be preserved in the presidential library and be available for record requests only after 12 years, according to reports this month. Obama’s ruling comes during the transition to a presidency led by Donald Trump who, during a Republican debate on March 3 said, “We should go for waterboarding and we should go tougher than waterboarding.”

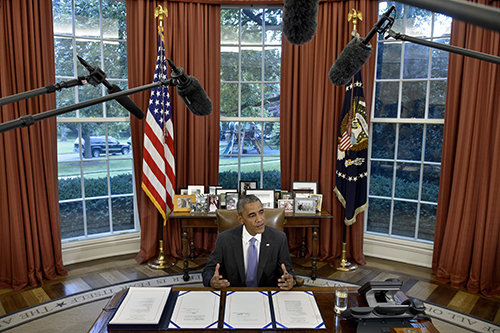

Obama’s decision to keep the report classified is at odds with his pledge to run “the most open and transparent [administration] in history.” On his first day in office, Obama issued a memorandum to the heads of executive departments and agencies urging them to embrace transparency. CPJ and civil rights groups have documented how, in the following years, his administration aggressively prosecuted leakers, surveilled journalists in leak investigations, used the state secrets privilege to suppress evidence in courts about torture and the government’s no fly list, and set a record for the use of legal exceptions in responding to freedom of information act requests. In 2013, CPJ published a special report, “The Obama Administration and the Press,” that was critical of the administration’s record on transparency.

With a new administration taking power under a president-elect whose actions so far–including his refusal to release his tax returns, ditching the press pool on occasion after being elected and, by late December, not holding a press conference since his electoral victory–run counter to a transparent administration, journalists and press freedom advocates said they are concerned about access and commitments to transparency.

“There was an obvious hostility towards the press during the campaign, at campaign rallies, and I wonder if that could be carried out in office,” said Leonard Downie Jr., a former executive editor at The Washington Post who wrote CPJ’s Obama report. “I’m concerned about access to the workings of government for the media and whether access will be any tighter than during the Obama administration.”

CPJ contacted Hope Hicks, spokesperson for the Trump transition team, for comment but its calls were not answered. The communications office of the president-elect’s transition team did not immediately respond to CPJ’s request for comment sent via email.

The Obama administration has responded to criticism of its record, saying it invested in declassifying documents and modernizing systems for proactive disclosure of government data. And, in a letter to the editor in the New York Times in August, White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest said Obama should be given more credit for his work on transparency.

In 2013 Attorney General Eric Holder tightened the rules allowing federal agents to subpoena records from journalists. The Obama administration has also published visitor logs to the White House, created a national declassification center, and required federal agencies to publish data online. The Obama administration’s positions on these views are important, not only because they affect the work of journalists in the U.S. but also because they serve as a global standard. For example, the administration advocated for greater transparency through the creation of the Open Government Partnership in 2011, a multilateral initiative to get governments to commit to increasing transparency. Press freedom was added to the partnership’s agenda during its summit earlier this month.

“This administration has done some very important work on declassification and the volume of declassification is significant,” said Alex Howard, the deputy director of the Sunlight Foundation, a government transparency watchdog. “If we don’t acknowledge their progress, then we unfortunately can end up undermining the ability of reformers to do the work that we need them to inside of government.”

But Downie said that the overall trends of delays and issues over access were the same. “The Freedom of Information Act is still too slow, there are many exemptions, and that in trying to deal with principals in government, you’re still shunted to PR people,” he said. “And that obviously establishes a potential floor for the Trump administration to say, ‘Look, we’re just doing what the Obama administration [did]’.”

Jason Leopold, a reporter for Vice who regularly uses the Freedom of Information Act in his work, said, “In my experience it’s been worse than the Bush administration. Leopold, who has also worked for Al-Jazeera America and the nonprofit news site TruthOut, cited long delays, the overuse of Freedom of Information Act exemptions, and requests that were returned entirely redacted. “Oftentimes with these redactions when they assert national security or the deliberative process, I’ve appealed and I’ve gotten those redactions lifted, there is no national security issues involved there. It’s simply to protect these agencies from embarrassment,” he said.

Federal agencies have their own offices for dealing with inquiries and are legally required to act in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act. The number of requests they handle has spiked to a record-high, even while staffing and funding has not. According to an Associated Press study of all requests submitted to 100 federal agencies in 2015, in more than one in six cases in 2015, officers said they could not find the files requested. In over three-quarters of cases, requesters received redacted documents or nothing in response to their request. Despite the presumption of openness mandated by Obama, federal agencies under his administration are using a record number of exemptions, according to FOIAMapper, a website that maps government record systems and tracks agency responses to requests for information.

Under the Act, agencies must give notice within 20 business days if a request will be complied with, but a common complaint from journalists is frequent delays. Part of the problem is that the backlogs and delays at agencies dealing with requests have proven intractable over many administrations, said David Pozen, a professor at Columbia Law School who writes about national security law and information law. Last year, the federal agencies completed 769,903 requests, a 19 percent increase over the previous year, but hired only 283 new full-time workers, an increase of about 7 percent, according to the AP report published in March.

“There’s no doubt this administration could do better. But it’s also an extremely decentralized labor-intensive system when you have 700,000 requests coming in, in a given year,” Pozen said.

Attempts to reform the Act have been met with resistance–as a Freedom of Information Act request found. In 2014, the Department of Justice lobbied against a reform bill intended to modernize the Freedom of Information Act and enshrine Obama’s “presumption of openness” into law, as it was making its way through Congress. Government documents revealed through requests sent by the Freedom of the Press Foundation showed that the Department of Justice sent a memo to House members protesting some aspects of the reform. Trump’s appointee for attorney general, Jeff Sessions initially put a hold on an earlier version of the reform bill when it passed through the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2014, according to The Hill. He ultimately removed his opposition.

“It actually took a FOIA lawsuit to find out how the administration had tried to hurt FOIA reform,” said Leopold.

In July, the Senate unanimously voted a version of the reform bill into law, on the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Freedom of Information Act. The reform enshrined the presumption of openness into law, made it easier to access documents over 25 years old, and strengthened the Office of Government Information Services, an ombudsperson that resolves disputes between requestors and agencies, according to Margaret Kwoka, an associate law professor at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law.

However, the Senate did not authorize additional funding–a point raised by many of the journalists and press freedom advocates who spoke with CPJ–and the reform did not address some of the most commonly cited problems, including overuse of national security exemptions and limited capacity.

Journalists cite the CIA being requested to release the fifth volume of its internal history of the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion as one of the concrete successes since the law was passed.

Kwoka, who researches requests and implementation, said the reform was important but not “ground-breaking in terms of changing the overall method of transparency under FOIA.” Her research of 38,974 requests across six government agencies in 2013 found that in certain agencies over three-quarters came from commercial requestors. “A huge amount of FOIA resources are serving purposes other than those that we imagined, and it’s mostly happening because FOIA is a fallback option for everyone who has no other way of getting government information,” she said.

Kwoka said she thinks the government should do a better job proactively publishing categories of information that are most commonly requested, or making it easier for people to access their own files or records. Her position is one taken by prominent open government groups like the Sunlight Foundation.

Progress has been made in making data more accessible online, Howard said. The Obama administration has also experimented with different Freedom of Information Act models, including a pilot program in which agencies proactively post responses online.

For Leopold, however, Obama’s transparency memo, reform of the act, and the pilot projects are not enough to counterbalance what he sees as the problems with the Act. “They did the bare minimum,” he said.

The potential for changes and restrictions to the Freedom of Information Act during a new administration is limited, in part because Obama’s presumption of disclosure is already set into law, transparency advocates told CPJ. Kwoka added that although he had shortcomings, Obama set the right tone. She said that it can be hard to measure the effect of that tone, but “to the extent that personnel working in FOIA feel supported in trying to make a more transparent government, that can only be a good thing.” She said, “And when the opposite is true: officials have a very real fear about disclosing something they shouldn’t and the repercussions.”

Kwoka said Trump could change the overall tone toward openness of the administration, and said that he has already rejected standard practices related to the press pool.

Leopold said, “This is always been a battle to get documents, and I think that what will likely exist going forward is the same sort of bureaucracy that has existed for the past 15 years if not longer.” He added, “Obama ran a very tight controlled administration where leaks were prosecuted. And the leaks were rare. I think that under Donald Trump there’s going to be lots of leakers.”

[EDITOR’S NOTE: This blog post has been updated to reflect that Jason Leopold has also worked for Al-Jazeera America.]