Edward Snowden’s global travels have highlighted the chasm between the political posturing and actual practices of governments when it comes to free expression. As is well known now, the former government contractor’s leaks exposed the widespread phone and digital surveillance being conducted by the U.S. National Security Agency, practices at odds with the Obama administration’s positioning of the United States as a global leader on Internet freedom and its calls for technology companies to resist foreign demands for censorship and surveillance.

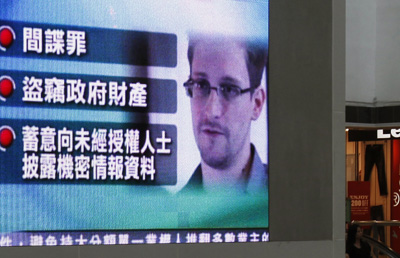

After disclosing his role as the leaker, Snowden left his Booz Allen Hamilton position in Hawaii for Hong Kong, which brushed aside U.S. extradition requests about the same time The South China Morning Post cited Snowden as saying the NSA was tapping into the networks of Chinese mobile phone providers. Authorities in Hong Kong operate under a one-country, two-systems model–that country being China, where the press is subjected to widespread surveillance and where ethnic minority journalists are jailed for reporting that doesn’t conform to official censorship rules.

It was on then to Moscow for Snowden. Russian officials, no doubt aware of Snowden leaks claiming the U.S. conducted surveillance of Dmitry Medvedev at a 2009 G-20 summit in London, initially professed having no jurisdiction over his travels. Surveillance of journalists is not unfamiliar to Russian authorities. A former Russian interior ministry official pleaded guilty last year to orchestrating the surveillance that led to the 2006 murder of investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya. With the main plotters of the killing still unpunished, the Politkovskaya case is far from being solved–as are 14 other journalist murders in Russia over the past decade, constituting one of the world’s worst records of impunity.

Snowden is said to be seeking asylum in Ecuador, with passage reportedly through Venezuela. Leaks of sensitive government information are growing less likely by the day in the two nations, which have moved aggressively to silence independent reporting. Venezuela has effectively eradicated independent broadcast outlets through its politicized regulatory system. Ecuador’s president, Rafael Correa, has pursued criminal prosecution of his critics. His government went even further this month, as CPJ’s John Otis recounted, with the adoption of sweeping legislation that criminalizes critical follow-up reporting and obligates news media to cover government-prescribed activities.

Back in the UK, where the story all began when the Guardian broke the first of Snowden’s leaks, the public has been debating a surveillance bill that critics derisively call the “snoopers charter.” The bill would expand the intelligence service’s ability to monitor digital communications, but one wonders how much weight David Cameron’s government gives to public debate. Among the latest revelations via Snowden and the Guardian: For 18 months, the British spy agency GCHQ has been secretly tapping into vast amounts of data carried by fiber-optic cable.