Liberian journalist Mae Azango’s courageous reporting on female genital mutilation, which made her the target of threats and ignited international controversy, has forced her government to finally take a public position on the dangerous ritual. For the first time, Liberian officials have declared they want to stop female genital mutilation, a traditional practice passed down for generations. Involving the total or partial removal of the clitoris, the ritual is practiced by the Sande secret women’s society. As many as two out of every three Liberian girls in ten out of Liberia’s 16 tribes are subjected to the practice, according to news accounts.

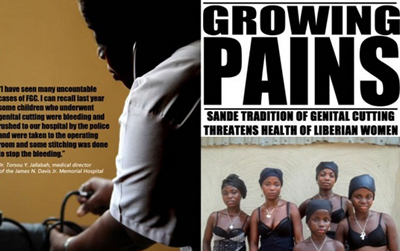

“Government is saying this needs to stop,” Gender and Development Minister Julia Duncan Cassell announced in an interview last week with Public Radio International’s “The World.” The minister was responding to a controversy sparked by Azango’s March 8 article, which was published by the leading independent daily FrontPage Africa. The story, headlined “Growing Pains: Sande Tradition of Genital Cutting Threatens Liberian Women’s Health,” explored the practices of the Sande secret society.

But Azango’s tenacity came with a price: People affiliated with the Sande secret society threatened the journalist with violence. Azango and her 9-year-old daughter were forced into hiding.

Interestingly, the Liberian government had quietly taken a position in opposition to female genital mutilation months ago. In a letter dated December 9, 2011, Joseph Janger, assistant minister for culture at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, requested all Sande activities be terminated by the end of last year. The decision apparently traces to a November 2011 ceremony at which Sande land used for the ritual was transferred to leaders of the men’s secret Poro society. President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and many of Liberia’s most powerful spiritual leaders attended the ceremony.

Still, the government’s position is not binding or even permanent. “There is no definite time,” Janger is quoted as saying in an interview with FrontPage Africa, referring to the requested shutdown of Sande activities. “It could last for three years, four years, 10 years.”

And, of course, the Liberian public never knew of government’s position. That is, until Azango’s report caused a national and international controversy and pressured the government to speak openly. “We never knew about it. No journalists knew it,” Azango told CPJ today. Even Sirleaf’s spokesman. Jerelinmik Piah, said he was not aware of any effort to halt Sande activities.

Azango welcomed the government’s public statement–with a dose of skepticism. “Implementation is a problem. It’s still going on as I speak to you,” Azango told CPJ today. She said the government has yet to prove that the announcement is no more than a public relations exercise. “They just did that to respond to pressure; the controversy was too much. They were under pressure to say something,” she added.

Through a news alert, advocacy with international institutions such as the U.N. mission in Liberia, as well as a social media campaign with the hashtag #MaeAzango, CPJ helped internationalize this local case and rally people to demand that Liberian authorities protect Azango. CPJ followed up with a letter to Sirleaf–Africa’s first female head of state and a Nobel Peace Prize winner for her work on women’s rights–urging her to use her moral authority and political leadership to ensure Azango’s safety. Amnesty International also released a global public statement calling on the Liberian government to act. The Society of Professional Journalists through the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism followed suit with a letter to Sirleaf stating “we do not condone family members having their lives threatened,” referring to Azango who reports for New Narratives, a reporting project run by alumni of the school. With reporting from the international press and social media attention generated by New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, the pressure mounted on Liberian authorities.

Initially, Liberian authorities appeared dismissive of the threats against Azango, with presidential spokesman Piah accusing international groups of wanting to “dictate” the government’s actions, according to local journalists. Under pressure, Liberia’s Ministry of Information finally issued a public press statement that said “the attention of the Government of Liberia is seriously drawn to reported threats on the life of a Liberian female journalist.” Signed by Press Secretary Isaac Jackson, the statement said “all necessary precautionary measures have been put in place to ensure that all those associated with the investigation are safe.”

Azango told CPJ today that she is moving more freely but that she was still assessing the situation as her safety is still not guaranteed. The journalist, who won a grant from the U.S.-based Pulitzer Center in November for reporting on reproductive issues, remains undeterred. While keeping a low profile, she has continued to report on female genital mutilation.